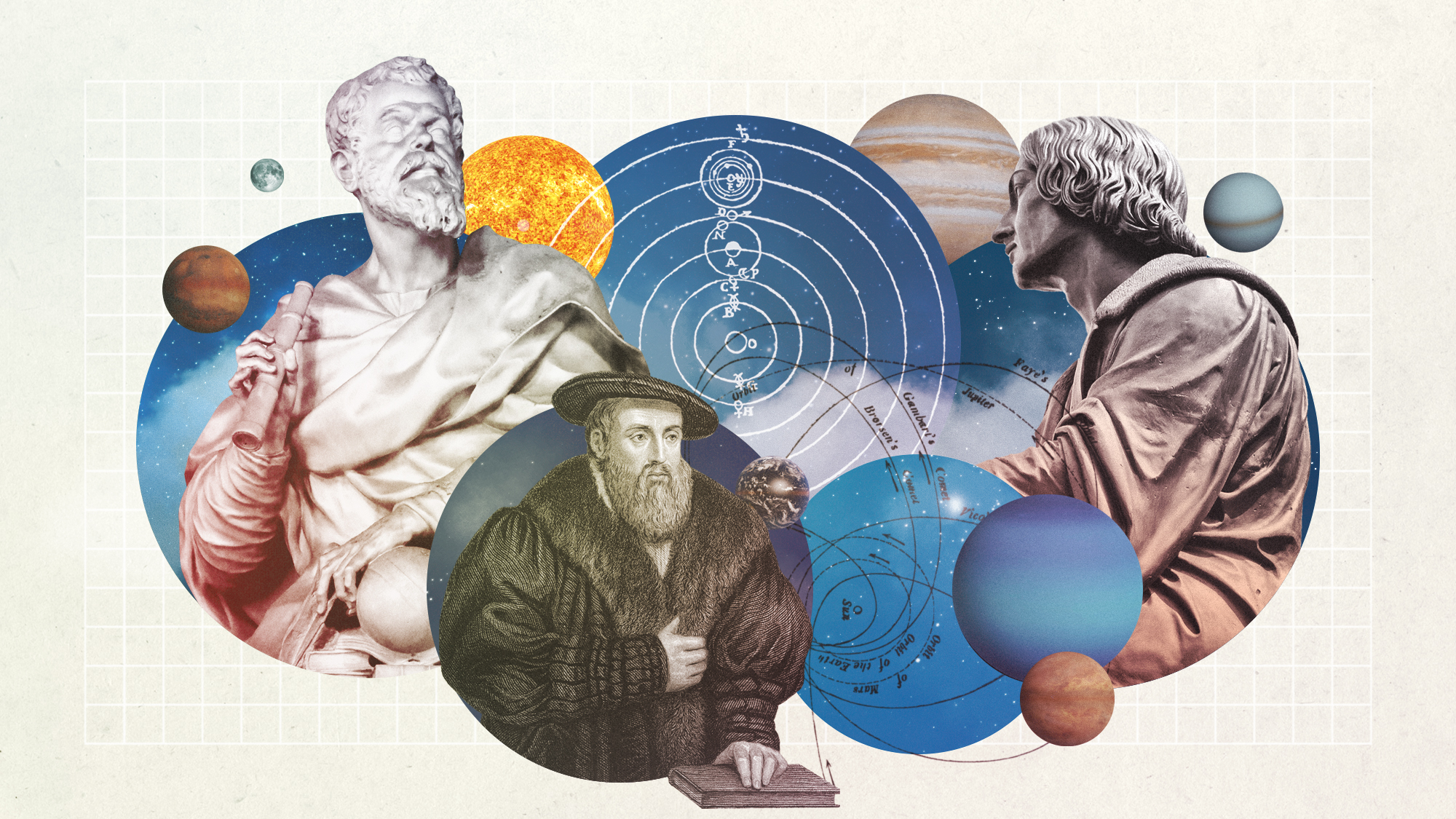

Heliocentrism explained in 60 seconds: ideas that changed the world

The discovery that Earth revolves around the Sun laid the foundations for modern physics

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

In this series, The Week looks at the ideas and innovations that permanently changed the way we see the world.

Heliocentrism in 60 seconds

The heliocentric theory is the idea that the Sun is at the centre of the solar system and that everything else – planets, asteroids, comets and the rest – revolves around it.

Prior to heliocentrism, the dominant belief was that all celestial bodies revolved around Earth. This theory, called "geocentrism", was popularised by Greek astronomer Claudius Ptolemy in the second century. Like many observers, he pointed out that the Sun, Moon and stars appeared to move across the sky, indicating that the Earth sat at the centre of the universe.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Ptolemy's idea were subsequently questioned by tenth century Iranian astronomer Abu Sa'id al-Sijzi and by 11th century Egyptian-Arab astronomer Alhazen. But geocentrism continued to dominate Western astrology theories for many centuries before starting to fall out of favour from the 1500s, as astronomers including Nicolaus Copernicus, Galileo Galilei and Johannes Kepler discovered evidence that the Earth is not fixed but rather moves around the Sun. That discovery led to the rise of heliocentrism.

As our understanding of space and the solar system have improved, heliocentrism has become universally accepted as the truth about the Earth’s position in the universe. However, a 2014 survey by the National Science Foundation found that 26% of Americans did not know that the Earth revolves around the Sun.

How did it develop?

Copernicus is credited with the invention of the theory of heliocentrism, although he was by no means the first astronomer to describe a Sun-centred universe.

According to science news site Futurism, the earliest mention of this idea dates back to 200BC, to a man known as Aristarchus of Samos. However, the theory did not take flight until Copernicus produced a short treatise titled "Commentariolus" ("Little Commentary"), which he distributed to fellow astronomers and scholars.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

The 40-page manuscript outlined his heliocentric theory, which was based on seven principles – including the incorrect notion that "all the spheres rotate around the Sun, which is near the centre of the universe".

Although some of Copernicus' ideas would later be disproved, he "resolved the mathematical problems and inconsistencies arising out of the classic geocentric model and laid the foundations for modern astronomy", according to Universe Today.

Along with his own observations of the motions of the planets, Copernicus based his ideas on previous theories from classical antiquity and the Islamic World. These earlier sources of inspiration included work by Indian astronomer Aryabhata, who in AD499 had published a treaty titled "Aryabhatiya" in which he "proposed a model where the Earth was spinning on its axis and the periods of the planets were given with respect to the Sun", according to the astronomy news site.

Copernicus was also influenced by the work of Nilakantha Somayaji, who published a commentary on Aryabhata’s treaty titled "Aryabhatiyabhasya" during the 15th century.

But while Copernicus was eager to share such insights, he feared that the publication of his theories would lead to condemnation from the Church. These concerns led him to withhold the publication of much of his research until a year before he died. It was only in 1542 that Copernicus sent his now-famous treatise to Nuremberg to be published.

Nearly a hundred years later, Kepler, Galileo and Isaac Newton further popularised the heliocentric model. Newton and Kepler produced a mathematical foundation to explain the motions of the planets around the Sun with incredible precision.

Meanwhile, armed with his telescope, Galileo collected a wealth of observational evidence that undermined the geocentric theory. Galileo’s advocacy of Copernicus' theories resulted in his house arrest, after he fell foul of the Catholic Church.

How did it change the world?

The understanding that the Earth is not the centre of the universe, and that it is not orbited by other planets and stars, changed people's perception of their place in the universe forever.

Copernicus' theories helped to inspire a total rethink of our understanding of physics, influencing the concepts of gravity and inertia. These ideas were more fully articulated by British mathematician, physicist and astronomer Sir Isaac Newton, whose "Principia" formed the basis of modern physics and astronomy.

Beyond science, the discovery that the Earth was not at the centre of everything made many people question the very nature of their existence, and that of religion - earning scientists the ire of the Church in the process. The Vatican only rectified its persecution of Galileo in 1992, when Pope John Paul III formally closed a 13-year investigation into the Church’s condemnation of the great Italian astronomer.

Joe Evans is the world news editor at TheWeek.co.uk. He joined the team in 2019 and held roles including deputy news editor and acting news editor before moving into his current position in early 2021. He is a regular panellist on The Week Unwrapped podcast, discussing politics and foreign affairs.

Before joining The Week, he worked as a freelance journalist covering the UK and Ireland for German newspapers and magazines. A series of features on Brexit and the Irish border got him nominated for the Hostwriter Prize in 2019. Prior to settling down in London, he lived and worked in Cambodia, where he ran communications for a non-governmental organisation and worked as a journalist covering Southeast Asia. He has a master’s degree in journalism from City, University of London, and before that studied English Literature at the University of Manchester.

-

Political cartoons for February 18

Political cartoons for February 18Cartoons Wednesday’s political cartoons include the DOW, human replacement, and more

-

The best music tours to book in 2026

The best music tours to book in 2026The Week Recommends Must-see live shows to catch this year from Lily Allen to Florence + The Machine

-

Gisèle Pelicot’s ‘extraordinarily courageous’ memoir is a ‘compelling’ read

Gisèle Pelicot’s ‘extraordinarily courageous’ memoir is a ‘compelling’ readIn the Spotlight A Hymn to Life is a ‘riveting’ account of Pelicot’s ordeal and a ‘rousing feminist manifesto’

-

Row over pole-dancing skeleton

Row over pole-dancing skeletonTall Tales And other stories from the stranger side of life

-

UFO hearing: why is Washington suddenly embracing aliens?

UFO hearing: why is Washington suddenly embracing aliens?Today's Big Question Speculation of extraterrestrial life has moved from ‘conspiracy fringe’ to Congress

-

Pentagon whistleblower claims government hiding alien technology

Pentagon whistleblower claims government hiding alien technologyfeature A former intelligence worker claims the government is secretly holding vehicles of ‘non-human origin’

-

China plans to land astronaut on the moon by 2030, official says

China plans to land astronaut on the moon by 2030, official saysSpeed Read

-

Baby born using three people’s DNA

Baby born using three people’s DNAfeature And other stories from the stranger side of life

-

Scientists have watched the end of the world

Scientists have watched the end of the worldfeature And other stories from the stranger side of life

-

Space tourists face sex bureaucracy

Space tourists face sex bureaucracyfeature And other stories from the stranger side of life

-

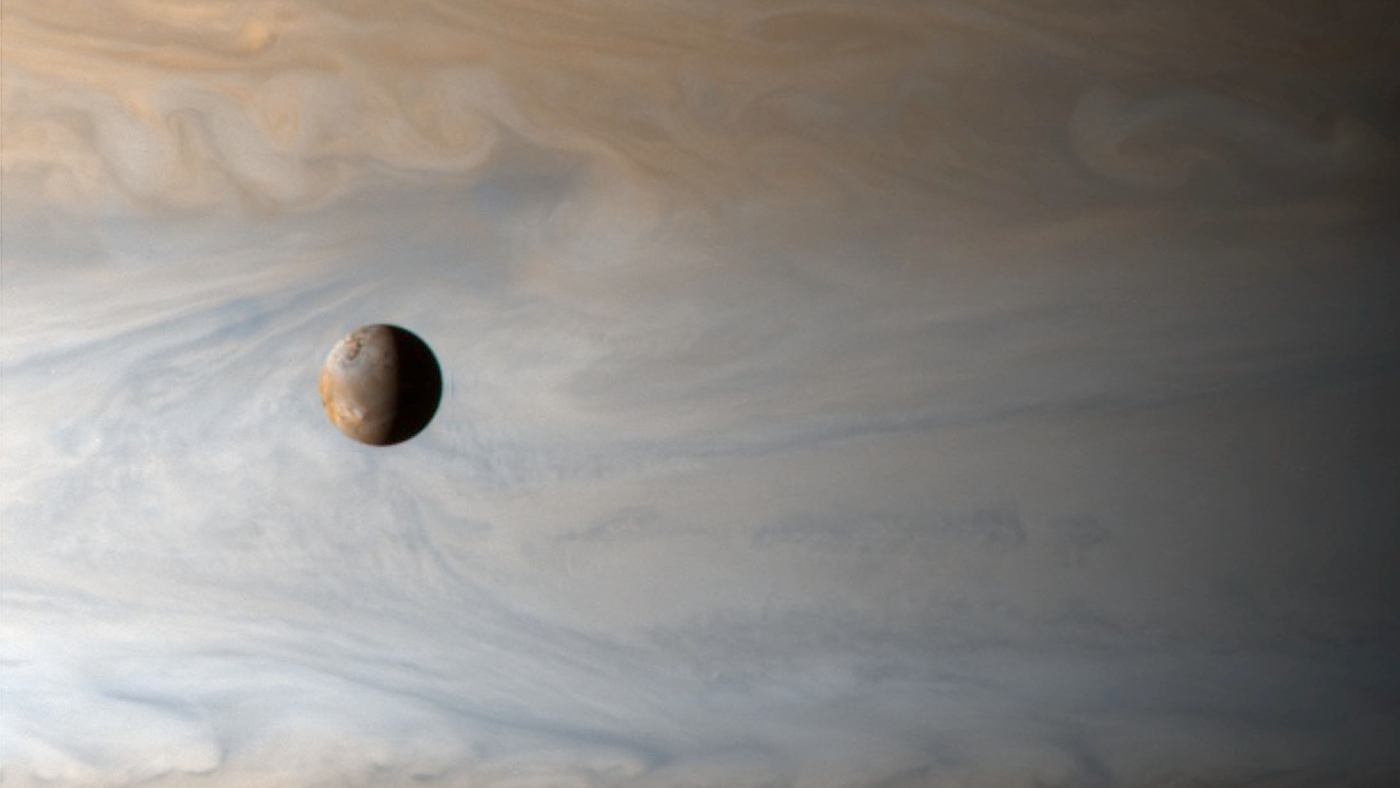

Juice: the European space mission to find life on Jupiter’s moons

Juice: the European space mission to find life on Jupiter’s moonsfeature Three of Jupiter’s moons are home to large, underground oceans that could support life