Sterling: which way now for the pound?

During the Scottish referendum the pound took centre stage – but what lies in store now for sterling?

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

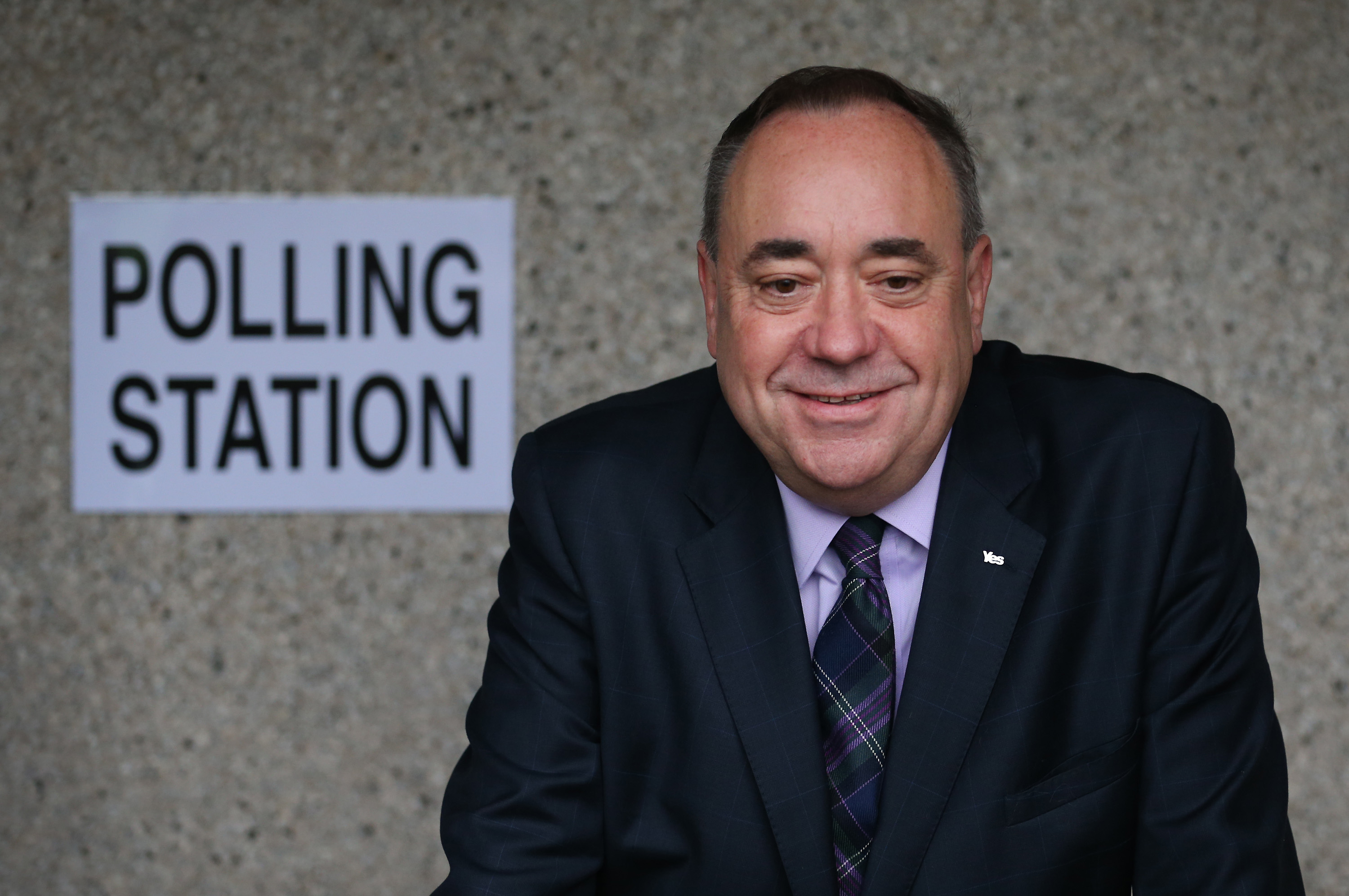

In the run-up to the Scottish election last month, quite a bit of misinformation was spread about the pound. Over the summer, it had fallen from $1.72 to $1.61 against the US dollar. The increase in the ‘yes’ vote was blamed.

This was quite wrong. If you look at the pound against the euro over the same period, the two currencies were flat. The same applies to the pound against most other senior currencies (by senior, I mean widely-traded currencies such as the Japanese yen). The fall in the pound against the dollar, in fact, had little to do with the Scots at all (except on that one panicky weekend where the polls showed in favour of ‘yes’). It was entirely a function of enormous US dollar strength.

When the ‘no’ vote won, everyone noted that the pound was breaking out to new highs against the euro. Nobody mentioned the fact that it actually fell against the dollar the next day. It was all a great example of how numbers are manipulated by politicians and the media to suit agendas.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

So now that the referendum is over, what’s next? Looking first at the pound against the dollar, I see $1.70 as a huge level. During periods of pound weakness – such as 1993-99 and 2009 to date – the $1.65-1.70 area caps all pound rallies. But during periods of sterling strength – 1987-92 or 2003-08 – $1.70 becomes the floor. If sterling can break above that level convincingly, there’s not a lot to stop it going all the way back to $2.

But we’d need a real spate of good economic news over an extended period for that to happen. For now, I’d say $1.60 or just above is fair value. News about the UK economy was so strong in the early part of this year that at one stage it looked like it was going to go through $1.70. But over the summer, the dollar became hugely popular and caught a massive bid (in other words, lots of people were keen to buy it). As for the next move, it’s all about politics. Next May’s election could be a very close call. I suspect the perceived outcome will determine where the pound goes.

At its conference in September, Labour pledged – among other things – a mansion tax, 50% income tax for higher earners and increased NHS spending. Whether you agree with these notions in principle or not, I don’t think the currency markets will like them. The numbers don’t seem to add up. So the end result will probably be a bigger debt and a larger overspend (deficit) for Britain – neither of which are good for sterling. Moreover, attacks on the rich (and there will be lots of such crowd-pleasing rhetoric in the lead up to May) will cause some capital flight from the UK – and thus selling pressure on sterling.

Whatever you may think of the Tories, the books are in better shape than they were four years ago. And if I was to bet on it, I’d say that the Tories will probably just scrape the election, with David Cameron deemed by the undecided to be more electable than Ed Miliband. But it is going to be close.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Broadly speaking, if Labour surge ahead the pound will weaken – it will prefer the Tories. On the downside, $1.50 and $1.40 are both areas of strong support. I would be very surprised to see $1.50 breached, let alone $1.40. $1.40 is the point to which sterling plunges at points of maximum uncertainty – in the wake of 2008, for example, or on Black Wednesday in 1992. It would take quite a sequence of events to get us there now. So my outlook is for the pound to trade in a range in-and-around the $1.60s for the time being – $1.57 the low and $1.66 the high.

Sterling versus the euro is much harder to call. There are so many conflicting factors affecting the euro, from the economic strength in northern Europe, to the weakness of the south. At the time of writing, sterling is in a strong uptrend against the euro. Such trends can last for many years. There will be resistance at the current price of €1.29- €1.30 but I suggest that over the next six to 12 months, the pound will edge towards the €1.40 mark. Downside support should be found around €1.25.

I think we’ll see rates rise here in the UK before they do so on the continent – although they’ll probably rise by a lot less than people fear. Low rates are the new norm – perhaps a rise of 0.25% in the latter half of 2015 and another 0.25% in 2016. I doubt we’ll see hikes here before the election, despite the supposed independence of the Bank of England. Rising rates should add to pound strength.

In short, if I were to rank the three currencies in terms of projected strength over the coming months, I’d say the dollar will be the strongest, followed by the pound and then, bringing up the rear, the euro. If you’re planning to trade, place your bets accordingly.

-

Will increasing tensions with Iran boil over into war?

Will increasing tensions with Iran boil over into war?Today’s Big Question President Donald Trump has recently been threatening the country

-

Corruption: The spy sheikh and the president

Corruption: The spy sheikh and the presidentFeature Trump is at the center of another scandal

-

Putin’s shadow war

Putin’s shadow warFeature The Kremlin is waging a campaign of sabotage and subversion against Ukraine’s allies in the West

-

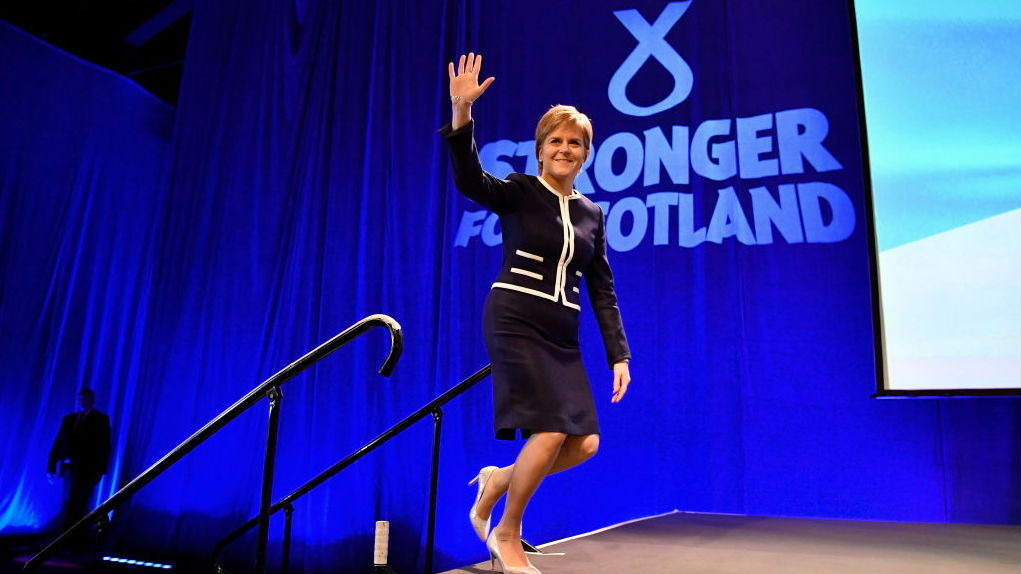

Could Scotland ditch the pound?

Could Scotland ditch the pound?In Depth Nicola Sturgeon to unveil new economic blueprint for independence

-

What happens to your cash if Scotland leaves the Union?

What happens to your cash if Scotland leaves the Union?In Depth Many questions remain about savings, ISAs and mortgages if the Scots decide to go it alone