Who are the Illuminati?

Belief that a ‘corrupt elite is secretly running the world’ is one of the longest-running and most widespread conspiracy theories of our time

It has become a “byword for a corrupt elite” ruling the world, said indy100, and supposedly boasts Beyoncé, Madonna, Jay-Z and Donald Trump among its members. The name “Illuminati” is “so powerful that it has begun to rule TikTok”, becoming last year’s “most talked-about counter-mainstream idea”.

The story is “pretty compelling” – but “that’s all it is, a story”. And it is one that the “stars themselves have shrugged off or even mischievously fuelled”. While most of the rumours surrounding the Illuminati and its members are fiction, the group was at one time real – though its influence was not nearly as vast and enduring as modern conspiracists claim.

How did the Illuminati start?

The idea of an “illuminati”, meaning “enlightened” or “illuminated”, has been around since the 15th century, wrote author and academic Chris Fleming. Early groups included the Spanish Alumbrados (the “illuminated”), who believed people could “attain direct communion with God” and thereby gain spiritual enlightenment without traditional worship or the sacrament. Alleged sympathisers include St Ignatius of Loyola, the founder of the Jesuit order, who was questioned by the Inquisition in 1527 over possible links.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

It was more than two centuries later that the Illuminati – as people understand it today – began. In 1776, Adam Weishaupt, former Jesuit and professor of natural and canon law at the University of Ingolstadt, Bavaria, founded a secret society that came to be called the Orden der Illuminati – the “Order of the Illuminati”.

To the outside world, Weishaupt appeared a “respectable professor”, said National Geographic. He was educated at a Jesuit school and was an “avid” reader at home, “consuming” books by French Enlightenment philosophers.

Like many at the time, Weishaupt came to believe “the monarchy and the church were repressing freedom of thought”, and that religious ideas were “no longer an adequate belief system to govern modern societies”. He wanted to find “another form of ‘illumination’, a set of ideas and practices that could be applied to radically change the way European states were run”.

At first, he considered joining the Freemasons, a group that was expanding across Europe, but he became disillusioned. Instead, he decided to found his own society, “handpicking” five of his “most talented” students to become members, said the BBC. The original name was Bund der Perfektibilisten, or the “Covenant of Perfectibility”, before he changed it to the Order of the Illuminati (literally the “Illuminated Ones”), to reflect the enlightened ideals of its educated members.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

The group’s first meeting was in a forest in Ingolstodt, where they established the rules of the order. Rituals included the use of aliases for anonymity and the adoption of symbols, such as their insignia: the Owl of Minerva, symbolising wisdom, sitting on top of a book. They also had three levels for members: novices; minervals; and illuminated minervals, referencing the Roman goddess of wisdom Minerva.

The order quickly grew, numbering between 2,000 and 3,000 members by 1784, with lodges in Italy, France, Belgium, Holland, Denmark and Switzerland. Members included doctors, lawyers and intellectuals, allegedly including German writer Johann Wolfgang von Goethe – although this is disputed.

But the society didn’t last long. In 1785, Karl Theodor, Duke of Bavaria, outlawed secret groups, including the Illuminati. Two years later, the Duke declared an edict with harsher punishments for members, including the death penalty. From 1785 onwards, the “historical record contains no further activities of Weishaupt’s Illuminati”, said Britannica. Yet, the order has continued to figure “prominently in conspiracy theories for centuries”.

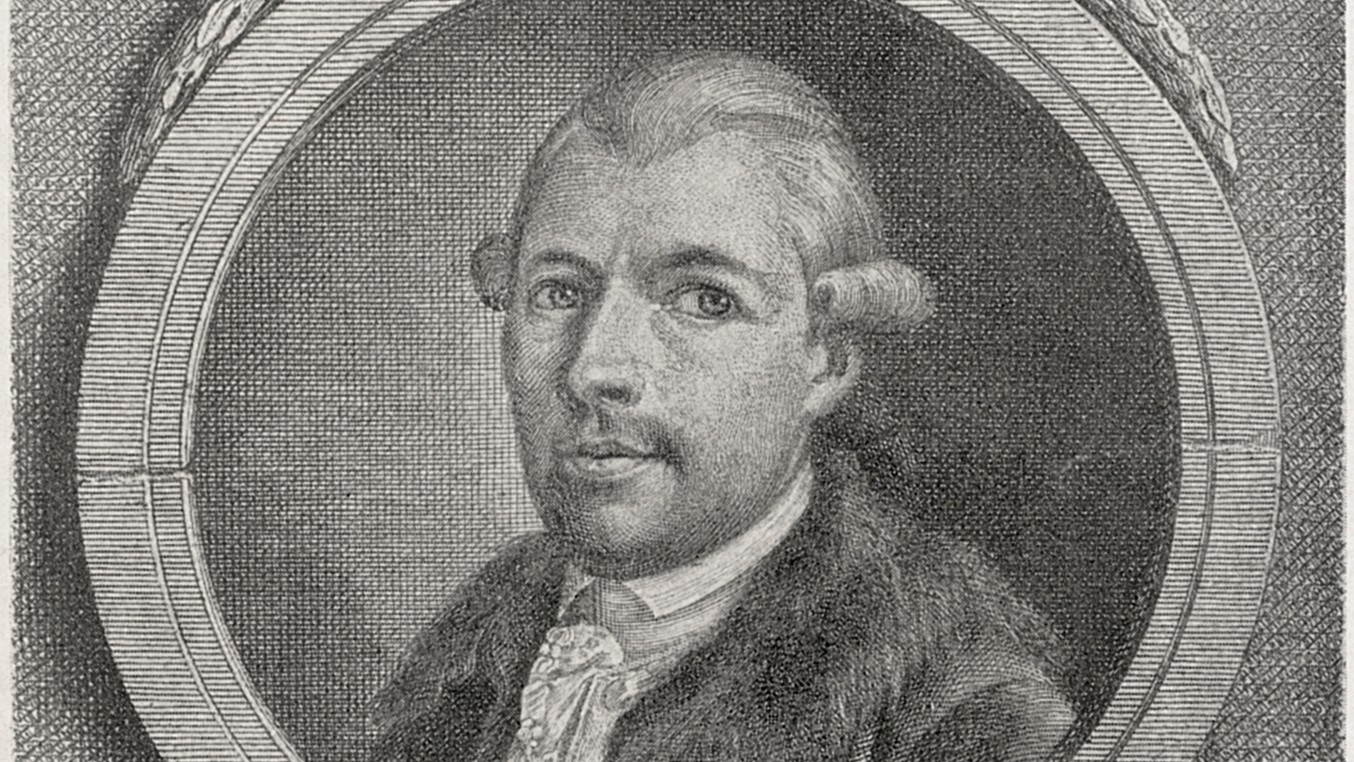

An illustration of Johann Weishaupt, founder of the Order of the Illuminati

How did the conspiracy develop?

Conspiracy theories about the Illuminati began almost when they were forced to disband. Its enemies claimed the group wanted to overthrow monarchs and priests and transform society.

In what was “perhaps the world’s first conspiracy theory”, said the BBC, in 1797 Jesuit priest Abbé Augustin Barruel wrote a four-part history of the French Revolution, which he attributed to the secret work of the Illuminati and Freemasons. Barruel is “generally regarded as one of history’s most famous conspiracy theorists”, according to history professor Claus Oberhauser on The Conversation.

Across the Atlantic, the order was the “bogeyman” of the fledgling US republic, said The Associated Press. George Washington wrote a letter saying that “no one” was more “truly satisfied” than him that the threat of the Illuminati had been avoided. Third president Thomas Jefferson was also accused of being a member.

The conspiracy theory has partly survived due to its links to the mythology of the founding fathers in America. But it was the Russian Revolution that led to the Illuminati becoming a “monster” theory, Illuminati expert Michael Taylor told the BBC. The Russian empire and monarchy were replaced by their “polar opposite” – and, like the French Revolution, it was an “equally traumatic, dramatic event”.

Today’s idea of the Illuminati is far removed from its Bavarian origins, author and broadcaster David Bramwell told BBC Future. The “totally unsubstantiated” modern image of the group mostly comes from the “era of counter-culture mania, LSD and interest in Eastern philosophy” that dominated the mid-1960s.

“It all began somewhere amid the Summer of Love and the hippie phenomenon, when a small, printed text emerged: ‘Principia Discordia’.”

“Principia Discordia” preached a form of anarchism and promoted civil disobedience ranging from practical jokes to hoaxes. It was, said the BBC, a “parody text for a parody faith” called “Discordianism”.

Some of the main proponents of this ideology were writers Robert Anton Wilson and Kerry Thornley, who wanted to bring chaos back into society by spreading “misinformation through all portals – through counter-culture, through the mainstream media”, Bramwell said.

Wilson and Thornley then turned their theories into a book, “The Illuminatus! Trilogy”, which became a “surprise cult success”. It was even transformed into a play, “launching the careers of British actors Bill Nighy and Jim Broadbent”.

But it was the arrival of the internet that turned the idea of a global elite conspiring to rule the world from a niche belief to a global conspiracy theory.

Why do people believe in the Illuminati?

If there is “one thing social media likes even more than conspiracy theories, it’s Easter egg hunts: searching for hidden clues”, said indy100. “The Illuminati has those in abundance, most notably the so-called ‘Eye of Providence’ – an eye set within a triangle, which happens to feature on the reverse of the American one-dollar bill.”

Other associated symbols include pentagrams, goats and the number 666. Conspiracy theorists often analyse public events for evidence of Illuminati influence.

This has given birth to an entire cottage industry. The number of books on the Illuminati is “staggering”, said V13.net, running to the thousands. Some of them “assert the Illuminati are the progeny of lizard-like aliens; others maintain the Illuminati are part and parcel of a vast Jewish conspiracy; a few say the Illuminati no longer exist; and still others present their group as the true Illuminati and provide written manifestos and instructions on how to join.”.

It is “basic human nature” to believe in secret groups such as the Illuminati, said Julian Baggini in The Guardian. “We are constantly on the lookout for both patterns and agency”, as both are essential for our survival – but “if the Illuminati is real, it’s got to be the least secret secret society in the universe”.

Politicians are not immune, either. In 2018, Canada’s former defence chief Paul Hellyer told The Lazarus Effect" podcast there was a “secret cabal that’s actually running the world”.

Four years later, then US president Joe Biden unwittingly fanned the conspiracy theory flames when he referred to a coming “new world order” during a speech. Biden was referring to “the shifting sands of geopolitical relations in response to Vladimir Putin’s invasion of Ukraine”, said The Independent. However, for conspiracy theorists, such comments are seen as further evidence that there is a “puppet-master overlord, hell-bent on global domination and busy manipulating international events to achieve his villainous ends”.

What is the New World Order?

Illuminati believers also tout theories about the “New World Order” – a “shadowy elite force” that, they claim, wants to bring about a “totalitarian world government”, said the Institute for Strategic Dialogue think tank. This “grand ongoing conspiracy” to exert control over the media, civil society and democracy is often blamed for global events and disasters.

Supporters of the New World Order theory believe “even the powerful US government is now just a puppet government”, said Modern Diplomacy in 2021.

The New World Order is “not so much a single plot as a way of reading history”, said New York Magazine. “Suspicions surrounding a shadow Establishment” can be traced back to the rise of Freemasonry in the 1700s, but it was “the past century’s global wars, political realignments, and media innovations that gave new purchase to this age-old paranoia”.

The New World Order theory has resonated with right-wing extremist and militia groups – some claim that gun control is proof that the Order is pushing the US government to restrict individual freedoms.

Is the Illuminati theory antisemitic?

With its “language around elites”, the theory is often mixed with antisemitic tropes, reinforcing the “narrative of Jewish people controlling global agendas”, said ISD.

Not long after Barruel’s history of the French Revolution was published, he was “sent a letter” by a man called Jean Baptiste Simonini, who alleged that Jews were also part of the conspiracy.

“This letter – the original of which has never been found – continues to shape antisemitic conspiracy thinking to this day,” said Oberhauser on The Conversation.

The belief that the Illuminati had “infiltrated the ranks of European Jewish bankers in the 19th century” fed into the creation of the “Protocols of the Elders of Zion”, the “transcript” of an invented meeting of Jewish leaders plotting world domination published in Russian in 1903, said the UCL historian Michael Berkowitz.

This hoax document led to the idea that “bankers/Jews/Illuminati were behind the Bolshevik Revolution – as well as the creation of the Federal Reserve system in the US”.

These conspiracy theories became particularly prevalent in the interwar years, said the American Jewish Committee, when “fascist propaganda claimed the Illuminati were a subversive element which served Jewish elites who were behind global capitalism and Soviet communism and were plotting to create a New World Order”.

Who is supposedly a member?

Numerous pop-culture icons have been accused of links to the Illuminati over the years, including Madonna, Kim Kardashian and LeBron James.

Beyoncé was accused of being a member after making a diamond shape – a so-called Illuminati sign – with her hands during her performance at the 2013 Super Bowl. Her husband Jay-Z is also said to be part of the order and allegedly hides its symbols in his videos. Even Taylor Swift’s love for the number 13 is seen as proof that she is a member.

Michelle Williams, Beyoncé, Kelly Rowland perform during the 2013 Super Bowl half-time show

Some musicians seem to enjoy deliberately playing with symbols connected to secret societies. For instance, Rihanna has incorporated Illuminati images into her music videos and even jokes about the theories in the video for “S&M”. It featured a montage of fake newspaper headlines, with one declaring her “Princess of the Illuminati”.

David Rockefeller, Henry Kissinger, Jacob Rothschild and Queen Elizabeth II were all rumoured to be members. Katy Perry once told Rolling Stone the theory was the preserve of “weird people on the internet”, but said she was flattered to be named among supposed members: “I guess you’ve kind of made it when they think you’re in the Illuminati!”

Does AI encourage belief in the Illuminati conspiracy?

The explosion of generative artificial intelligence over the past few years has prompted concerns that AI could entrench or disseminate conspiracy theories, given that it regularly creates or conveys falsehoods. But a study published last year in Science suggested that, for some conspiracy theorists, a fact-based conversation with an AI chatbot could “pull them out of the rabbit hole”, said technology researchers Dana McKay and Johanne Trippas on The Conversation.

More than 2,000 participants discussed a conspiracy they believed with an AI system called “DebunkBot”, knowing that they were talking to a chatbot. About 20% of those in the “treatment” group showed a “reduced belief in conspiracy theories” after a three-round back-and-forth conversation, as the bots were “not perceived as having an ‘agenda’”, making them seem “more trustworthy”. Scientists found that the AI chatbots were mostly accurate, too.

Although chatbots can “promote misinformation or conspiracy”,; if their underlying data is wrong, or biased, chatbots can “put together an argument”, which is more persuasive and effective against fake beliefs than “a simple recitation of facts”. The “personalised approach”, with counterarguments “relevant to their beliefs”, made participants “feel heard”, said Psychiatrist.com. One participant who believed in the Illuminati conspiracy said the AI had “shifted their perspective for the first time”, adding that the response “made real, logical sense”.

-

October 1 editorial cartoons

October 1 editorial cartoonsCartoons Wednesday's political cartoons include Pete Hegseth's warrior ethos, taxes in a shutdown, and the battle of Portland

-

‘Friendflation’: the increasing cost of maintaining a social life

‘Friendflation’: the increasing cost of maintaining a social lifeUnder the Radar Cost-of-living squeeze has left some feeling priced out of social events and struggling to keep up friendships

-

What’s behind Europe’s sharp drop in illegal migration?

What’s behind Europe’s sharp drop in illegal migration?Today's Big Question Fall in migrant crossings won’t head off tougher immigration clampdowns