Agincourt: why Netflix’s The King has upset the French

The Battle of Agincourt has long been celebrated, but France has a different perspective more than 600 years on

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

A new Netflix film depicting the Battle of Agincourt has caused consternation across the Channel, amid claims that it is historically inaccurate and “anti-French”.

The Shakesperian telling of King Henry V’s victory at Agincourt “has long upset the French”, The Telegraph reports. But according to the head of the newly renovated Agincourt museum, Christophe Gilliot, Australian film director David Michod’s new depiction of the battle - The King - is no better and “rife with historical errors”.

Gilliot said: “I’m outraged. The image of the French is really sullied. The film has Francophobe tendencies. The British far-right are going to lap this up, it will flatter nationalist egos over there.”

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

The film, which features Timothee Chalamet as Henry V, whitewashes English “raping and pillaging”, according to Gilliot. The Telegraph says Chalamet’s performance as a “sensitive leader dragged into a conflict” has also come under fire.

French academics have previously accused English soldiers of acting like “war criminals” during the battle, while Gilliot described Henry V as having “a sinister look and behaviour to match”.

“We are disgusted because in two hours, this type of film demolishes all the mediation work we have been doing here (at the museum) over the past eight years and the research of historians,” said Gillot. “It’s really worrying that one can re-write history to this extent and it is hard for us to fight against this.”

What happened?

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

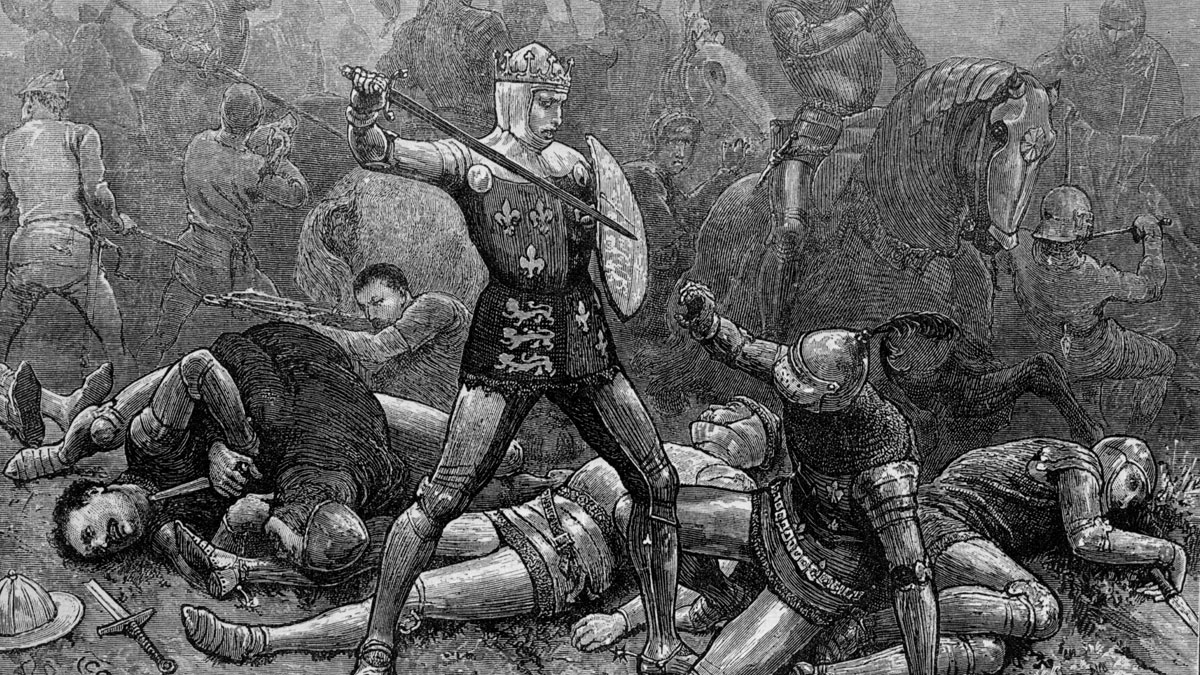

The Battle of Agincourt was fought during the Hundred Years’ War between England and France. Henry V, England’s young king, led his forces to victory at the clash in northern France.

How did it start?

Two months earlier, Henry and his 11,000 troops laid siege to Harfleur in Normandy. Although the town surrendered within weeks, the English suffered heavy casualties. Henry decided to march them northeast to Calais, where he hoped to meet the English fleet and return home.

However, a 20,000-strong French army blocked their path, greatly outnumbering the exhausted English troops. Fighting broke out on Friday October 25, 1415 (St Crispin’s Day), near modern-day Azincourt, in northern France. Henry V led his troops into the fighting. Despite the English being outnumbered by a reported three to one, they were victorious on the muddy battlefield.

Aren’t the numbers of troops on each side disputed?

Yes. In her book Agincourt: A New History, Anne Curry estimates that the French only outnumbered the English by three to two (12,000 Frenchmen against 7,000 to 9,000 English). She describes the battle as a “myth constructed around Henry to build up his reputation as a king”. However, most historians still think the English were outnumbered at least three to one – or even more.

What sort of weapons were used?

Among those favoured by the English were lead-weighted hammers, poleaxes, mauls and falcon-beaks. However, the weapon that gave England the biggest advantage over the French was the longbow. As Hannah Ellis-Petersen explains in the Daily Telegraph, this allowed them to shoot six aimed arrows a minute which could wound at 400 yards, kill at 200 and penetrate armour at 100 yards.

Why are the English accused of war crimes?

In 2008, French academics accused English soldiers of acting like “war criminals” during the battle. The French “were met with barbarism by the English”, argued one, who said the English set fire to prisoners and killed noblemen who had surrendered – after an order from their king to slaughter captives. However, it is believed the French would have behaved similarly had they won.

What were the battle’s legacies?

It destroyed the confidence of France and ushered in a new era, during which Henry married the French king’s daughter and Henry’s son, Henry VI, was made heir to the throne of France.

Culturally, it has left an impact. The battle is the centrepiece of Shakespeare’s play Henry V and continues to be used as a reference point. This summer, Chancellor George Osborne told MPs the battle showed a strong leader defeating “an ill-judged alliance between the champion of a united Europe and a renegade force of Scottish nationalists”.

English Heritage will mark this year’s anniversary at Portchester Castle in Hampshire.

Was the V-sign invented at Agincourt?

It has long been claimed that the “V-sign” hand gesture was first introduced to British body language 600 years ago in the Battle of Agincourt. It is said that the French had threatened to cut off the middle and index fingers of any enemy archers they captured to stop them from using their bows. However, when the English won, they supposedly held up their two bowing fingers to show that they remained intact.

Curry says this is a “twentieth-century myth, although so far it has proved impossible to find where and when a link to Agincourt was first suggested”. She says there is a 15th-century chronicle written by a monk that mentions mutilated limbs and a fictional King’s speech written by two 15th-century Burgundians that talks about the French boasting about cutting off the fingers of English archers. But she says none of the texts say that the victorious archers stuck up their fingers after the battle.

The V-sign was used to signify “victory” by Winston Churchill in the 1940s and later came to signify “peace” in the 1960s, although flipped the other way around it is regarded as an offensive gesture in the UK.

-

Film reviews: ‘Send Help’ and ‘Private Life’

Film reviews: ‘Send Help’ and ‘Private Life’Feature An office doormat is stranded alone with her awful boss and a frazzled therapist turns amateur murder investigator

-

Movies to watch in February

Movies to watch in Februarythe week recommends Time travelers, multiverse hoppers and an Iraqi parable highlight this month’s offerings during the depths of winter

-

ICE’s facial scanning is the tip of the surveillance iceberg

ICE’s facial scanning is the tip of the surveillance icebergIN THE SPOTLIGHT Federal troops are increasingly turning to high-tech tracking tools that push the boundaries of personal privacy