Jordan: history and hospitality in a tough neighbourhood

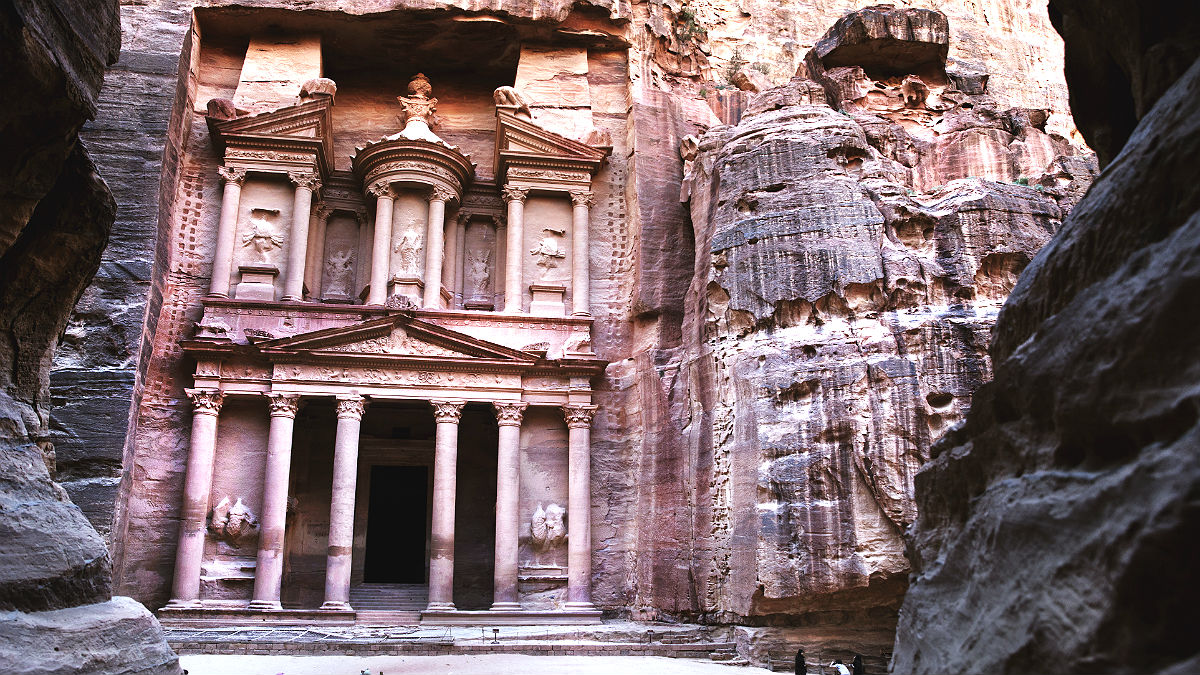

The old city of Petra, carved into the side of a ravine, is a spectacular example of Jordan's historical legacy

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

"We live in a tough neighbourhood," says our guide as he reels off a list of the troubled or troubling countries sharing a border with Jordan. Iraq, Syria, Saudi Arabia, Israel and the Palestinian territory of the West Bank are all within a couple of hundred miles of Amman airport, where we left behind a crowd of people shouting and cheering to celebrate the return of a student, just graduated from an American university.

"Even so," the guide continues, "this area has been a haven of stability and hospitality since Biblical times."That may be a rosy view of an infamously complex slice of history, but it touches on two of the qualities that define this part of the world: the sense of history as a long, winding path stretching back towards the dawn of time – and of the warm welcome extended to many of the people who have found their way to this contentious land.Trade and travel started early in Jordan, and many of today's visitors are attracted by the legacy of previous civilisations.

The stone city of Petra, for example, carved into the sandstone more than 2,000 years ago by the Nabataeans, who made their way through the inhospitable landscape by trading spices, scents and minerals from the Dead Sea with Romans, Egyptians and merchants from the Arabian peninsular.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

The town's most recent residents, the Bedouin, come down the ravine each day to ply their less romantic trade of souvenirs and rides on horses and camels. The horse rides at least serve a practical purpose - it's a six-mile round trip from the park entrance to the spectacular vantage point above Petra's monastery.

It's worth the walk, though, and not only for the vast façade of the Treasury, the best preserved of the ruins, which looms into view as you step out of a snaking, high-sided canyon. Imagine the Bank of England, carved into luminous sandstone.

The frontage bears the scars of two millennia of exposure – and of the potshots fired by locals hoping that its decorative urns contained treasure rather than solid rock – but it still projects a sense wealth and power.

A couple of miles further on, a steep and strenuous climb brings you out of the canyon for an elevated look at the largest of the buildings, the monastery, with the valley stretching out behind it.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

It will give you a taste for desert scenery, which is best satisfied at Wadi Rum, a high desert plateau dotted with rocky outcrops, about an hour from the southern city of Aqaba. The bleakly beautiful landscape is bound up with the legend of T.E. Lawrence, the British Army officer who passed through the area on his way to Aqaba, a journey immortalised in the David Lean film, Lawrence of Arabia.

It's not hard to imagine yourself in an epic film of your own as you race through the dunes of on the back of a pick-up truck, driven at speed by guides who scramble and bounce their way along a maze of sandy tracks. Their goal: an elevated, secluded spot from which to enjoy the silence of the desert and the vibrant colours of sunset.

The sites of Wadi Rum can also be enjoyed from the air, in hot air balloon ride booked from Aqaba.

This seaside city, which shares the Red Sea coast with Israel and Egypt, is rapidly establishing itself as Jordan's primary resort, where year-round warmth attracts swimmers, snorkellers and divers. The water is clear as well as warm, and alongside the fish and coral are man-made attractions for divers, including shipwrecks and a submerged American tank.

Jordan's other coastline caters to less energetic tastes. The Dead Sea is the lowest point on Earth, 400 metres below sea-level, and the extra oxygen at that altitude is reputed to have an invigorating effect.

So too is the salty water, which buoys up your body so that swimming is impossible. All you can do is lie back and drift around on the surface, stopping periodically to cake yourself in the mineral-rich mud from the seabed.

Whether or not it benefits your health, there's a child-like delight in slapping on the silky mud and bobbing around as if you've been exempted from the laws of physics. An absence of science to compensate for the excess of history.

-

Film reviews: ‘Send Help’ and ‘Private Life’

Film reviews: ‘Send Help’ and ‘Private Life’Feature An office doormat is stranded alone with her awful boss and a frazzled therapist turns amateur murder investigator

-

Movies to watch in February

Movies to watch in Februarythe week recommends Time travelers, multiverse hoppers and an Iraqi parable highlight this month’s offerings during the depths of winter

-

ICE’s facial scanning is the tip of the surveillance iceberg

ICE’s facial scanning is the tip of the surveillance icebergIN THE SPOTLIGHT Federal troops are increasingly turning to high-tech tracking tools that push the boundaries of personal privacy