Is austerity over and what did it achieve?

It has been the Tories' flagship policy since they came to power in 2010, but last week's election may have ended that

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

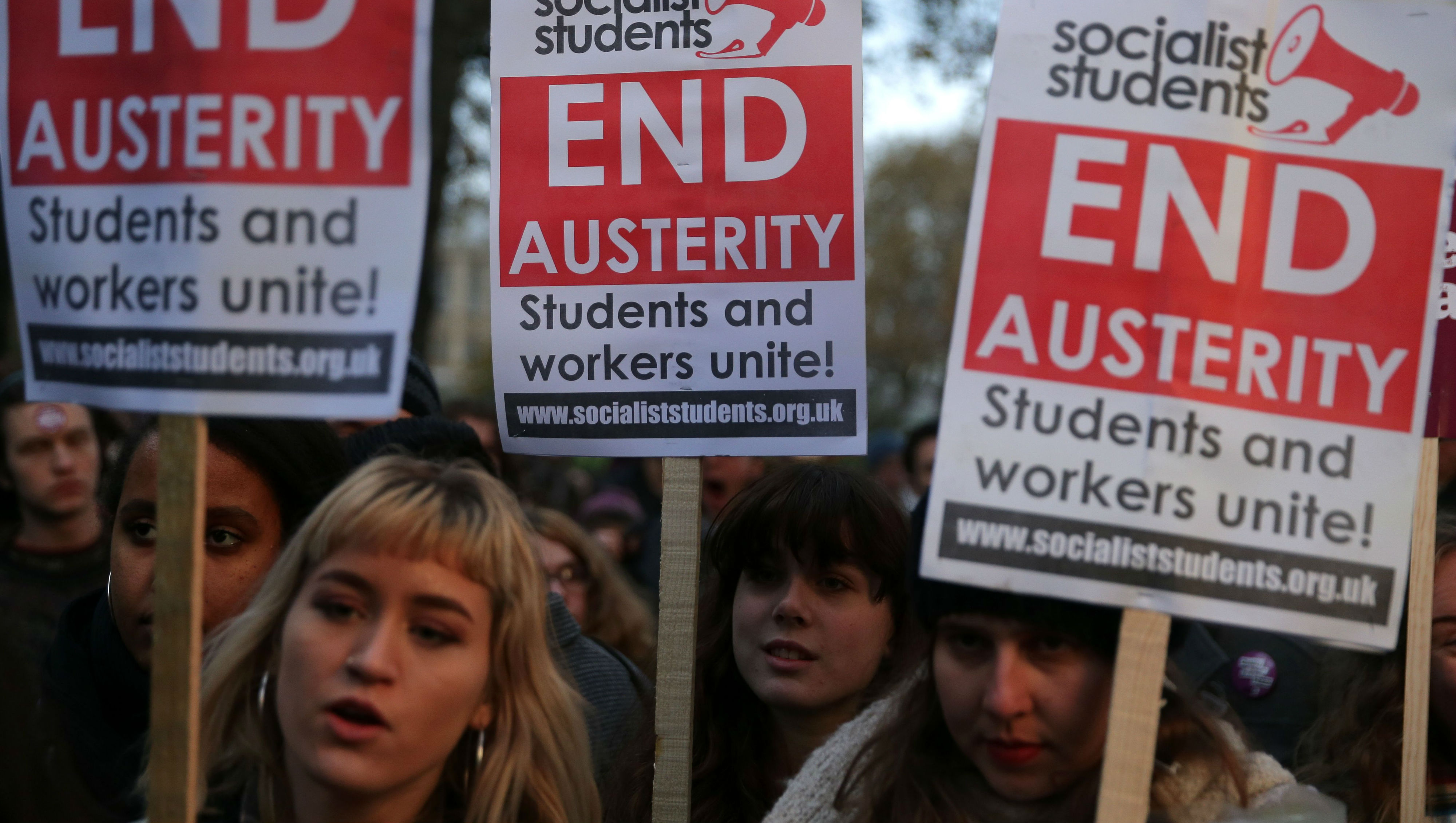

Jeremy Corbyn's Labour Party did not win the election last week, but the popular view is that it scored a massive political victory by defying predictions of an existential collapse.

Reports this morning suggest it may have done even better by forcing the Tories to ditch the austerity politics that have defined the party's period in government since 2010.

According to The Times, MPs at a meeting of the Tory backbench 1922 Committee warned Theresa May "they would refuse to vote for further cuts".

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

The paper adds: "Sources said that she accepted that voters’ patience with austerity was at an end after [Foreign Secretary] Boris Johnson, [Brexit Secretary] David Davis and a series of Tory MPs told her that she had misjudged the public mood."

Why was austerity introduced?

Restraint in government spending, known popularly by the policy's critics' term of "austerity", was at the centre of the Tory manifestos in 2010 and 2015.

The party argued the cuts were necessary after the banking crisis as the economic fallout had seen public spending rise and tax receipts fall, while the budget deficit - the gap between what is raised in tax revenue and paid out in spending - spiralled higher.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

In the financial year before the Tories came to power in a coalition in 2010, the deficit was close to £152bn, equivalent to almost ten per cent of GDP, says the Daily Telegraph.

Every year a country runs a budget deficit, the national debt increases - it has surged from £1trn to £1.7trn in the past seven years - and that means the money the government spends each year servicing debt has also increased, to a reported £36bn last year.

So, to free up money to spend on public services, the argument was the country needed to tighten its belt, get rid of the deficit and start paying down the debt.

Did it work?

The interesting thing about the policy politically is that the Tories claim at least relative success while Labour, among others, claims it has been a failure.

Arguments in favour tend to focus on the decrease in the deficit, which fell to a post-crisis low of 2.6 per cent last year, implying that the rate at which the national debt is increasing is down by almost three-quarters.

However, that is partly a function of tax revenues and GDP increasing. The budget deficit was actually £52bn in cash terms last year, compared to £40.4bn the last time it was this low in proportional terms.

Herein lies Labour's criticism: the Tories are still stuck with a stubbornly high budget deficit despite having promised to get rid of the shortfall within five years.

Government spending has actually risen since 2010 in cash terms, from £673bn to a forecasted £802bn this year, but the value of public spending has declined significantly by as much as £25bn a year, accounting for inflation.

Critics say if the government had spent more, the economy would have recovered quicker and, as per the figures for last year, helped eliminate the budget deficit quicker.

So, has it all been worth it?

The Tories have historically pointed to economic positives: more people in work than ever and the fastest growing advanced economy in the world in 2014 and much of 2016, second only to the US for the year in between.

Given the global economic context, it is hard to imagine spending more on welfare would have improved these figures markedly.

There is also concern from the likes of Moody's, the credit rating agency, which said this week that the UK is "among the few highly rated European sovereigns whose public debt is still rising" and that further delays in cutting the deficit would be "credit negative", says the BBC.

If the UK's credit rating were to be cut markedly, there is a chance interest rates on government debt would soar, increasing the cost of servicing the national debt, which is money that could be spent on public services.

On the other hand, 130 economists wrote to The Observer before the election saying they agreed with Labour's policy, which was to balance day-to-day spending but borrow much more to invest in the economy.

In addition, noted economist Paul Krugman has written in support of the Keynesian argument that until the economic recovery is much stronger than now, budget deficits should be ignored - or even embraced.

"At some point, you do want to reverse stimulus," he writes. "But you don't want to do it too soon – specifically, you don't want to remove fiscal support as long as pedal-to-the-metal monetary policy [low interest rates] is still insufficient.

"Instead, you want to wait until there can be a sort of handoff."

What does the future hold?

Much of the argument is moot. Painful spending cuts were only going to be sustainable as long as they enjoyed public support and last week's election results seems to suggest this is waning - or has already been lost.

Unless we get another election, though, we're still going to have a Tory government. So what are they now proposing?

"When it comes to matching Labour's spending promises... May's room for manoeuvre is limited," says the Times.

"Philip Hammond, the chancellor, had already softened the Tories' deficit reduction programme by pushing back the deadline for balancing the budget to 2025."

In particular, Tory MPs are said to be calling for real-terms schools cuts to be scrapped and for more money to be pumped into an ailing social care system without "raiding pensioner benefits" or taking their homes.

Most probably this either implies an even slower path to fiscal consolidation - so more debt - or tax rises, which were notably not ruled out on the campaign trail.

We will find out more when the Tories make their deal with the Democratic Unionist Party and we hear the Queen's Speech - assuming we do.

The Conservatives are taking one day at a time for now.

-

The ‘ravenous’ demand for Cornish minerals

The ‘ravenous’ demand for Cornish mineralsUnder the Radar Growing need for critical minerals to power tech has intensified ‘appetite’ for lithium, which could be a ‘huge boon’ for local economy

-

Why are election experts taking Trump’s midterm threats seriously?

Why are election experts taking Trump’s midterm threats seriously?IN THE SPOTLIGHT As the president muses about polling place deployments and a centralized electoral system aimed at one-party control, lawmakers are taking this administration at its word

-

‘Restaurateurs have become millionaires’

‘Restaurateurs have become millionaires’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

French finances: what’s behind country’s debt problem?

French finances: what’s behind country’s debt problem?The Explainer Political paralysis has led to higher borrowing costs and blocked urgent deficit-reducing reforms to social protection

-

New austerity: can public services take any more cuts?

New austerity: can public services take any more cuts?Today's Big Question Some government departments already 'in last chance saloon', say unions, as Conservative tax-cutting plans 'hang in the balance'

-

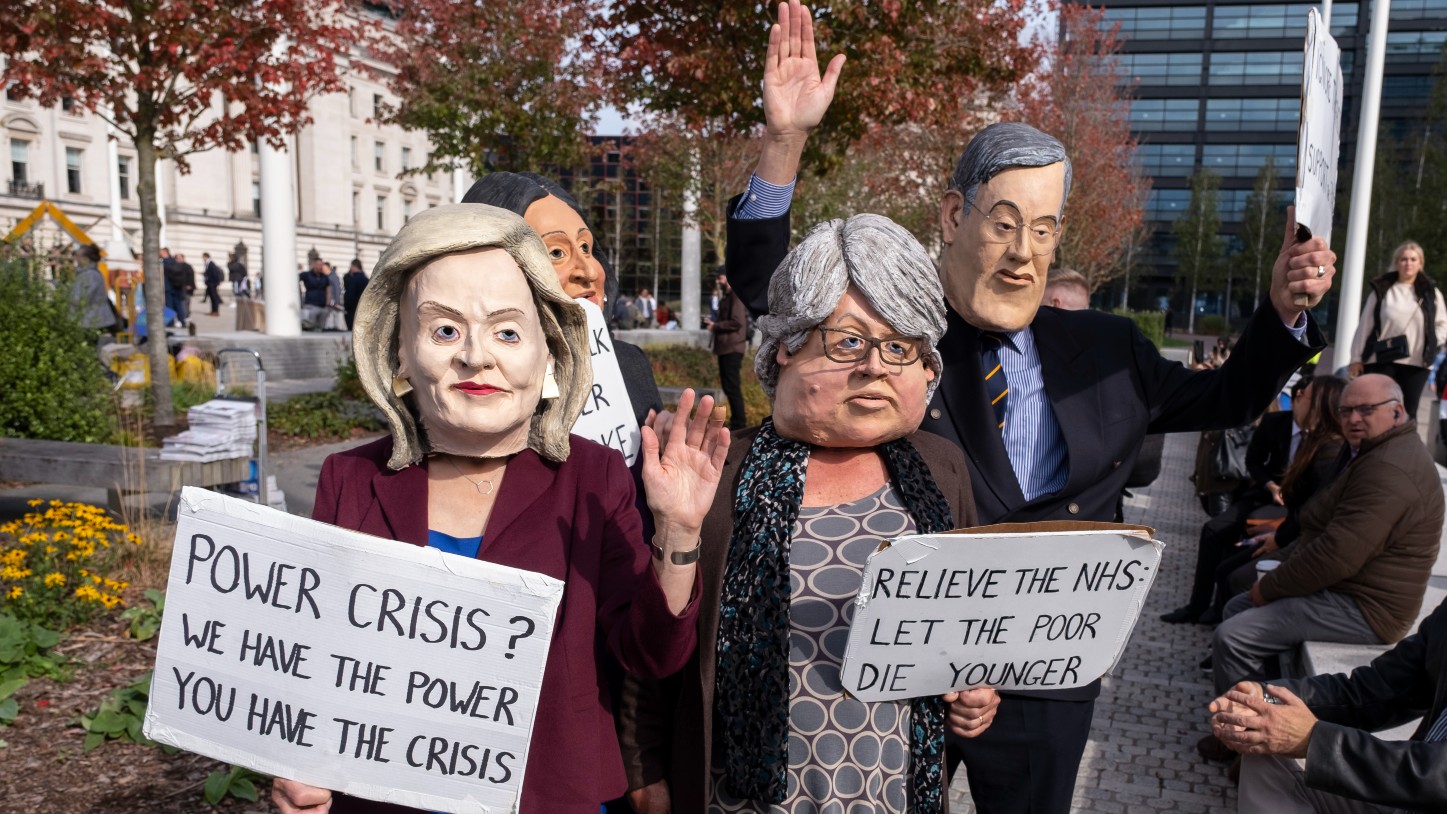

Liz Truss and Kwasi Kwarteng’s supply-side reforms

Liz Truss and Kwasi Kwarteng’s supply-side reformsfeature PM and chancellor are banking on cuts to regulations and tax in bid to stimulate growth

-

Do Tory tax cuts herald return of austerity?

Do Tory tax cuts herald return of austerity?Today's Big Question Chancellor U-turns on scrapping top rate tax but urges ministers to make public spending cuts

-

British wages are being squeezed - here’s why

British wages are being squeezed - here’s whyIn Depth Report says former Labour heartlands in the north of England have been hit hardest

-

No-deal Brexit would require emergency budget, says Hammond

No-deal Brexit would require emergency budget, says HammondSpeed Read Chancellor warns end to austerity plan due to be announced today could be cancelled in a no-deal scenario

-

End austerity or eliminate the deficit?

End austerity or eliminate the deficit?Speed Read Theresa May faces ‘stark choice’ as IFS warns of massive tax hikes needed to ease squeeze on public services

-

Surprise surplus gives Hammond wiggle room to splash the cash

Surprise surplus gives Hammond wiggle room to splash the cashSpeed Read Borrowing down and tax revenue up as figures reveal budget deficit lower than expected