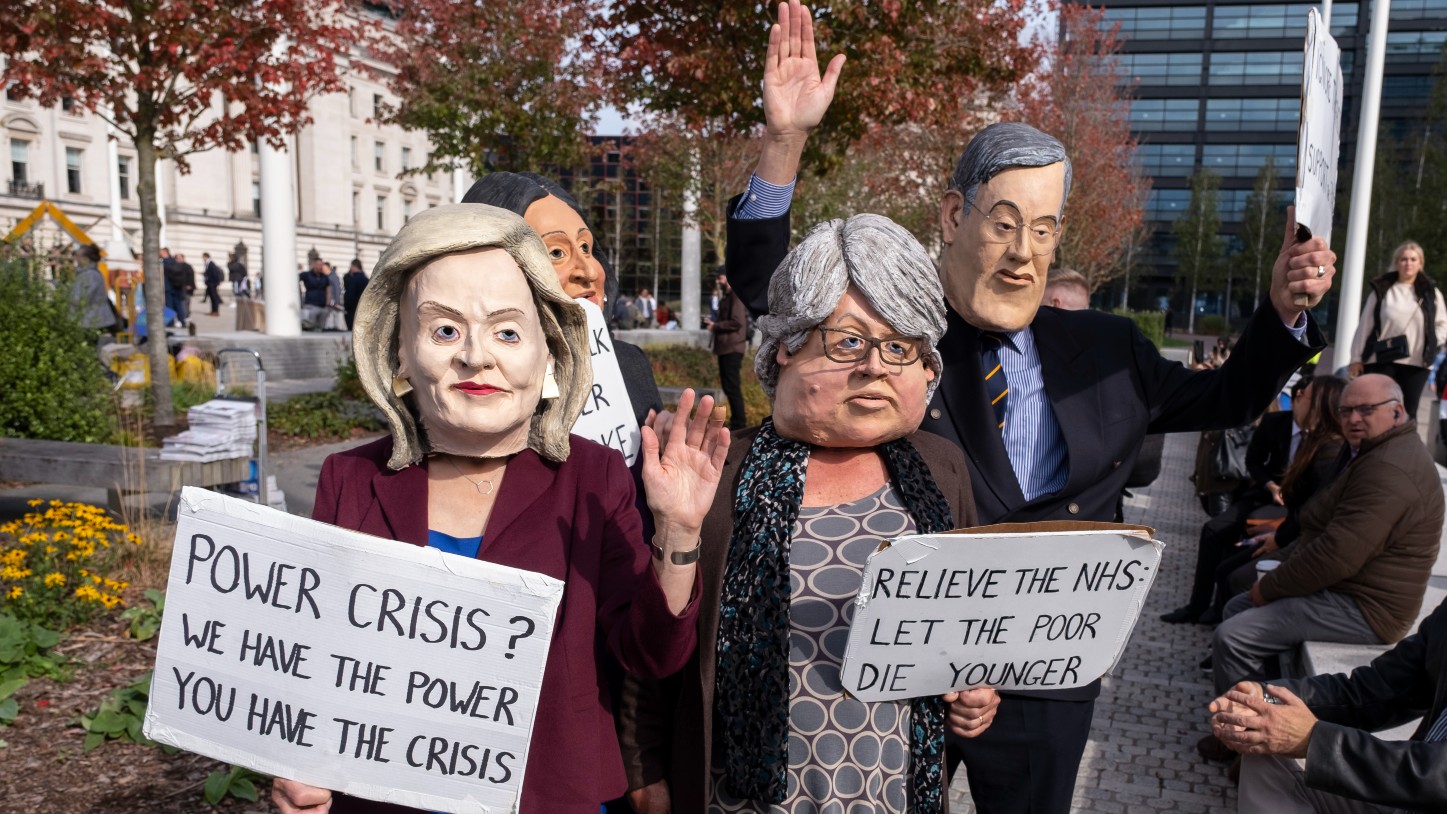

Liz Truss and Kwasi Kwarteng’s supply-side reforms

PM and chancellor are banking on cuts to regulations and tax in bid to stimulate growth

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Kwasi Kwarteng is to unveil his debt-cutting plan almost a month earlier than planned in a bid to reassure jittery markets following weeks of economic turmoil.

The chancellor will “rush forward” his statement and the release of forecasts from the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) to 31 October, said the Financial Times, as “he attempts to prove he can get a grip on the public finances and fill in a fiscal hole” left by £43bn of tax cuts.

The plan – to be revealed before the Bank of England votes on whether to raise interest rates for an eighth time this year – is expected to include further “supply-side” reforms aimed at growing the UK economy.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

What is supply-side economics?

The macroeconomic theory came to prominence in the 1980s under Margaret Thatcher in the UK and Ronald Reagan in the US, and is based on the idea that the supply of goods and services within the economy is a main driver of growth.

Supply-side economics is similar to “trickle-down” economics, in which wealth benefits are felt by all classes. However, the latter is based on the idea that targeted tax cuts are more effective than the general tax cuts and deregulation at the core of supply-side economics.

Such deregulation may include changes to rules on planning, childcare, immigration, agricultural productivity and digital infrastructure. Kwarteng’s plan is also expected to include further post-Brexit loosening of regulation governing the UK’s financial services sector.

Supply-side economics is visually represented in the so-called Laffer Curve, which charts the theoretical relationship between rates of taxation and government revenue. The curve was created by Reagan-era US economist Arthur Laffer, who argued that lowering tax rates boosts government revenue through higher economic growth.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

As Liz Truss and her allies have repeatedly stated, the key point is “growing the economic pie”, with the ultimate goal of benefitting everyone, rather than worrying about exactly how the pie is divided up.

This theory has been challenged by a series of economists in recent years. A London School of Economics analysis of 18 OECD countries between 1970 and 2020 found that big tax cuts for the rich increased the share of national income earned by the top 1%, but had no significant effect on the wider economy in terms of unemployment or GDP per capita.

What are the Truss government’s options?

Supply-side economics “used to have a bad name”, wrote economist Allison Schrager for Bloomberg. But “a more modern view” of the theory has won “converts on both the right and the left”, although “how to achieve it is dividing policymakers”.

One policy that Kwarteng may consider could be relaxing Britain’s strict Sunday trading laws, “which increases convenience for the consumer by allowing larger superstores to stay open for longer, giving shoppers greater choice and encouraging them to make purchases”, said The Independent.

“But the downsides of such a step have to be taken into account too,” the news site continued. The measure “could eat into the tactical competitive advantage awarded to smaller shops and increase the likelihood of their larger retail rivals cannibalising trade and developing a monopoly”, which would leave customers “with fewer options and held hostage to flatlining prices”.

The chancellor has already announced the introduction of new “investment zones” with greater tax reliefs and allowances and easier planning processes. Other reforms could include tax reliefs to companies developing low-carbon technologies; building new rail links between cities to encourage trade; and investing in a faster broadband network to support businesses.

The “long-term success” of the government’s growth plan “now largely hinges on these supply reforms”, said Ryan Bourne, chair in public understanding of economics at the Cato Institute think tank, in an article for Conservative Home. These supply-side plans “have always been more important that the modest net tax cuts”, he added.

Will it work?

A “key problem” with Kwarteng’s plan is that “there seems less scope for a supply-side boost than in the early 1980s”, said MoneyWeek.

The Times’s economics correspondent Arthi Nachiappan explained that “today the UK already boasts some of the lowest headline corporate tax rates among rich countries”. But these low taxes have “failed to generate substantive growth and productivity”, he added.

Pundits are suggesting that, having already bowed to political pressure to abandon the scrapping of the top rate of tax, the government’s supply-side revolution may be dead in the water.

Rather than stimulating the UK's economy, Truss’s first financial update as prime minister “very nearly killed it – and with it, perhaps, the notion that supply-side economics is a good fit for the challenges of the 21st century”, said Canada’s National Observer.

-

Local elections 2026: where are they and who is expected to win?

Local elections 2026: where are they and who is expected to win?The Explainer Labour is braced for heavy losses and U-turn on postponing some council elections hasn’t helped the party’s prospects

-

6 of the world’s most accessible destinations

6 of the world’s most accessible destinationsThe Week Recommends Experience all of Berlin, Singapore and Sydney

-

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule works

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule worksIn the Spotlight The law is at the heart of the Colbert-CBS conflict

-

Will Trump’s 10% credit card rate limit actually help consumers?

Will Trump’s 10% credit card rate limit actually help consumers?Today's Big Question Banks say they would pull back on credit

-

What will the US economy look like in 2026?

What will the US economy look like in 2026?Today’s Big Question Wall Street is bullish, but uncertain

-

Is $140,000 the real poverty line?

Is $140,000 the real poverty line?Feature Financial hardship is wearing Americans down, and the break-even point for many families keeps rising

-

Fast food is no longer affordable for low-income Americans

Fast food is no longer affordable for low-income AmericansThe explainer Cheap meals are getting farther out of reach

-

Why has America’s economy gone K-shaped?

Why has America’s economy gone K-shaped?Today's Big Question The rich are doing well. Everybody else is scrimping.

-

From candy to costumes, inflation is spooking consumers on Halloween this year

From candy to costumes, inflation is spooking consumers on Halloween this yearIn the Spotlight Both candy and costumes have jumped significantly in price

-

French finances: what’s behind country’s debt problem?

French finances: what’s behind country’s debt problem?The Explainer Political paralysis has led to higher borrowing costs and blocked urgent deficit-reducing reforms to social protection

-

Why are beef prices rising? And how is politics involved?

Why are beef prices rising? And how is politics involved?Today's Big Question Drought, tariffs and consumer demand all play a role