Science in extremis

How Rolex supports researchers in the coldest, deepest and darkest corners of the world

Freezing temperatures, deep water and dense jungle continue to pose challenges for explorers and researchers in the remotest places on Earth - people like Joseph Cook, Vreni Häussermann and Luc-Henri Fage.

While each has chosen a very different mission, all three work at extremes, relying on their resilience, ambition and dedication, as well as a creative approach to problem-solving. And each has been recognised with a Rolex Award for Enterprise.

Launched in 1976 to celebrate the 50th anniversary of the Rolex Oyster, the world's first waterproof wristwatch, the awards identify and support individuals who have advanced human knowledge and the wellbeing of communities around the world. They focus on innovative ventures in areas such as applied science and technology, exploration and the environment.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Joseph Cook: pushing scientific frontiers

Exploration can take all kinds of forms. For British scientist Joseph Cook it has meant a decade examining ice in minute detail in an attempt to understand a unique and remote ecosystem.

A glacial microbiologist with a PhD in microbial carbon dynamics, Cook carries out most of his fieldwork camped in Greenland on the largest continuous mass of ice in the northern hemisphere. Here he is able to explore the microscopic ‘frozen rainforest’ on the surface of the ice sheet, which remains, to a large extent, a scientific mystery.

As the recipient of a Rolex Award for Enterprise, Cook was able to take a team to the Greenland ice sheet in 2017 to explore how ice microbes engineer their survival in this hostile environment, and to study their influence on the climate. When ice melts, the availability of liquid water encourages the growth of algae, bacteria, and other microbes, which in turn contributes to further melting.

The Rolex award also funded the production of a documentary film, Ice Alive, which explains how Arctic microbes influence climate, nutrients, carbon cycles, and other aspects of our world and its systems.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

“We went to great lengths to make this a visually striking film that we hope is a pleasure to watch and communicates the otherwordly beauty and incredible complexity of the Arctic glacial landscape,” he says on his website, To The Poles. “We aim to educate, entertain and inspire others into exploring and protecting this most sensitive part of our planet in their own ways.”

Vreni Häussermann: saving the seas

Like Greenland, Chilean Patagonia, at the southern tip of South America, is one of the last real wildernesses left on earth. It is also under increasing pressure from climate change and other man-made issues.

Its coastline, spanning more than 50,000 miles, includes the most extensive fjord region in the world. In recent years economic development - including salmon farming, industrial fisheries and infrastructure projects - have had a considerable impact on the marine environment in the region.

German marine biologist Vreni Häussermann has been working there for more than 20 years, trying to preserve the unique location.

In 2003 she was appointed director of Huinay Scientific Field Station, the leading facility collating data and researching the area, a role in which she advises the Chilean government about conservation and sustainable resource management in the region. Three years later, her team submitted a proposal for a marine protected area in two fjords with unique cold-water coral banks.

The death of 337 sei whales, as well as whales, fish, shellfish, jellyfish and corals, in 2015, only served to strengthen her resolve to shield the unique environment from further harm.

Using the grant that accompanied her 2016 Rolex Award, Häussermann is planning to send a remotely operated vehicle equipped with thrusters, cameras and sensors to depths of 500 metres, where it will document a world never before seen by the human eye – and relay the resulting photographs and videos of marine life to Google Earth and YouTube.

She quotes the Senegalese forestry engineer Baba Dioum to explain her approach to underwater research: “We only conserve what we love, we only love what we understand, we only understand what we are taught.”

Luc-Henri Fage: preserving our past

While art historians still have only a hazy understanding of the origins of human creativity, most believe the oldest works of art consist of outlines left when prehistoric people held their hands against the walls of their caves and blew red pigment against the stone.

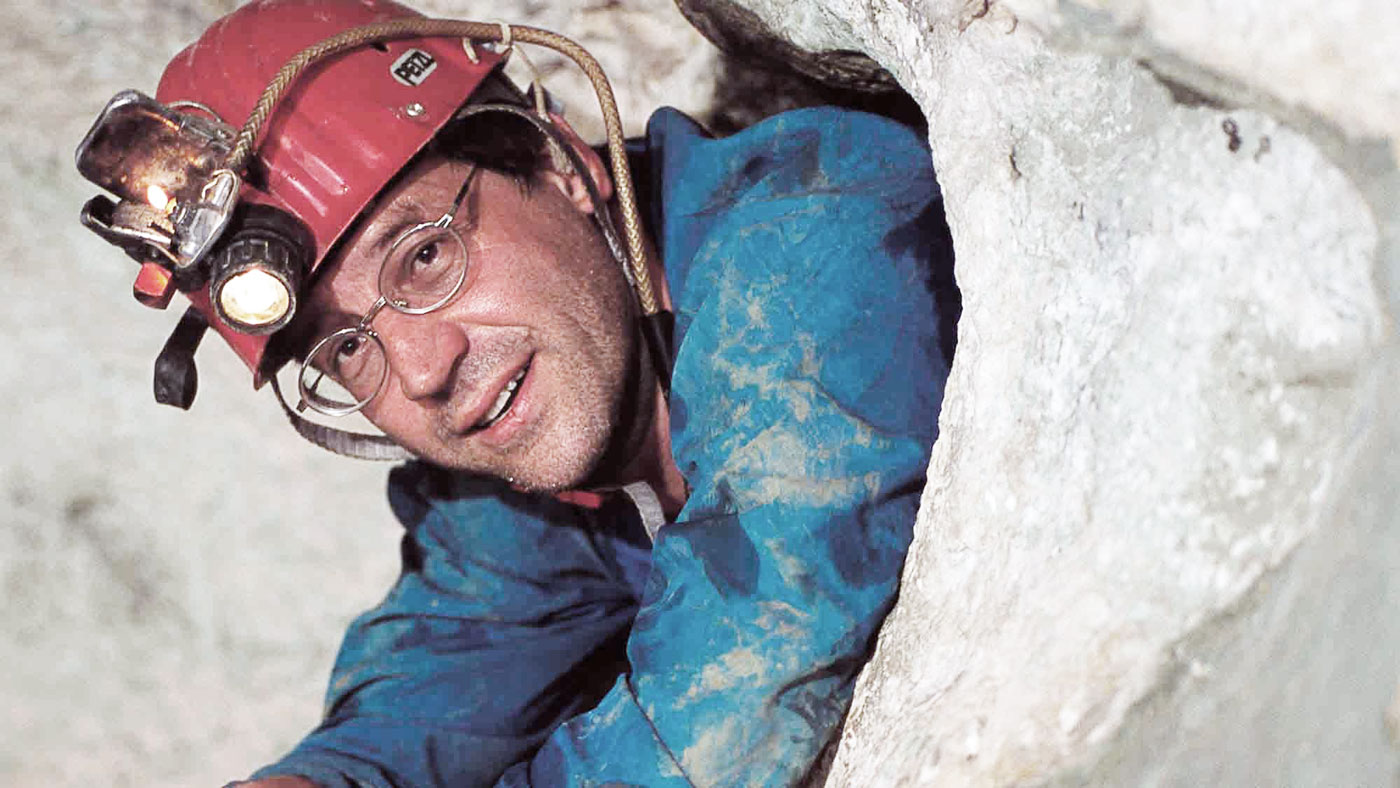

These hand stencils have been found all over the world. Examples from El Castillo in Spain featured in the opening moments of the recent BBC series Civilisations, which traced the progress of art from the moment of their creation to the present day. But the French explorer Luc-Henri Fage has dedicated his life to a more remote collection of similar paintings in Kalimantan, in the jungles of Indonesian Borneo.

His interest in the area’s lost art began in 1988, when he and two archaeologists - Jean-Michel Chazine of France and Pindi Setiawan of Indonesia - embarked on an expedition into the rainforest and discovered a series of ancient charcoal pictures. They were inspired to return several times to see what else was hidden in the remote jungle caves.

“Before we went there, Kalimantan, a region as big as France, hadn’t been visited by a single archaeologist,” says Fage, who received a Rolex Award for Enterprise in 2000. By 2011, he and his colleagues had found 1,938 hand stencils and other examples of rock art in 40 caves, identifying 30 recurrent motifs.

Since receiving the Rolex Award, Fage has campaigned for the creation of a national park to protect the Kalimantan mountains from the threat of mining for coal and limestone. Instead, he says, ecotourism could provide a sustainable income while preserving the ancient art works - which may be even more culturally significant than previously thought.

Recently discovered hand stencils on the neighbouring island of Sulawesi are at least 39,900 years old, according to research published in the journal Nature in 2014. That means they rival the rock paintings at El Castillo as the oldest human works of art. And the journey back in time may yet continue. “I predict that even older examples of cave art will be discovered on Sulawesi, and in mainland Asia, and ultimately in our African homeland,” says Chris Stringer of the Natural History Museum.

Rewarding enterprise

In their own ways, Cook, Häussermann and Fage represent the breadth of ambition and curiosity embodied in the Rolex Awards for Enterprise. On Greenland’s frozen tundra, at the fringes of South America and deep in the jungles of Borneo, each is pushing forward the frontier of knowledge.

“The Rolex Awards were designed to support those whose own spirit of enterprise mirrored the enterprising spirit on which the company was founded,” says Rebecca Irvin, Head of Philanthropy at Rolex. “The idea was to encourage new ventures rather than reward past achievements and to recognise people who were doing things differently, exploring beyond boundaries and bringing often unconventional and ground-breaking ideas to help change the world.”

-

Sepsis ‘breakthrough’: the world’s first targeted treatment?

Sepsis ‘breakthrough’: the world’s first targeted treatment?The Explainer New drug could reverse effects of sepsis, rather than trying to treat infection with antibiotics

-

James Van Der Beek obituary: fresh-faced Dawson’s Creek star

James Van Der Beek obituary: fresh-faced Dawson’s Creek starIn The Spotlight Van Der Beek fronted one of the most successful teen dramas of the 90s – but his Dawson fame proved a double-edged sword

-

Is Andrew’s arrest the end for the monarchy?

Is Andrew’s arrest the end for the monarchy?Today's Big Question The King has distanced the Royal Family from his disgraced brother but a ‘fit of revolutionary disgust’ could still wipe them out