Rolex on top of the world

On the 65th anniversary of the ascent of Everest, the feat looks no less remarkable

The early decades of the twentieth century bore witness to huge strides in aviation, as well as major expeditions to Antarctica and attempts to reach Everest, the roof of the world. In this era of adventure, it was no surprise that Rolex would begin to test its watches in some of the most extreme conditions on earth.

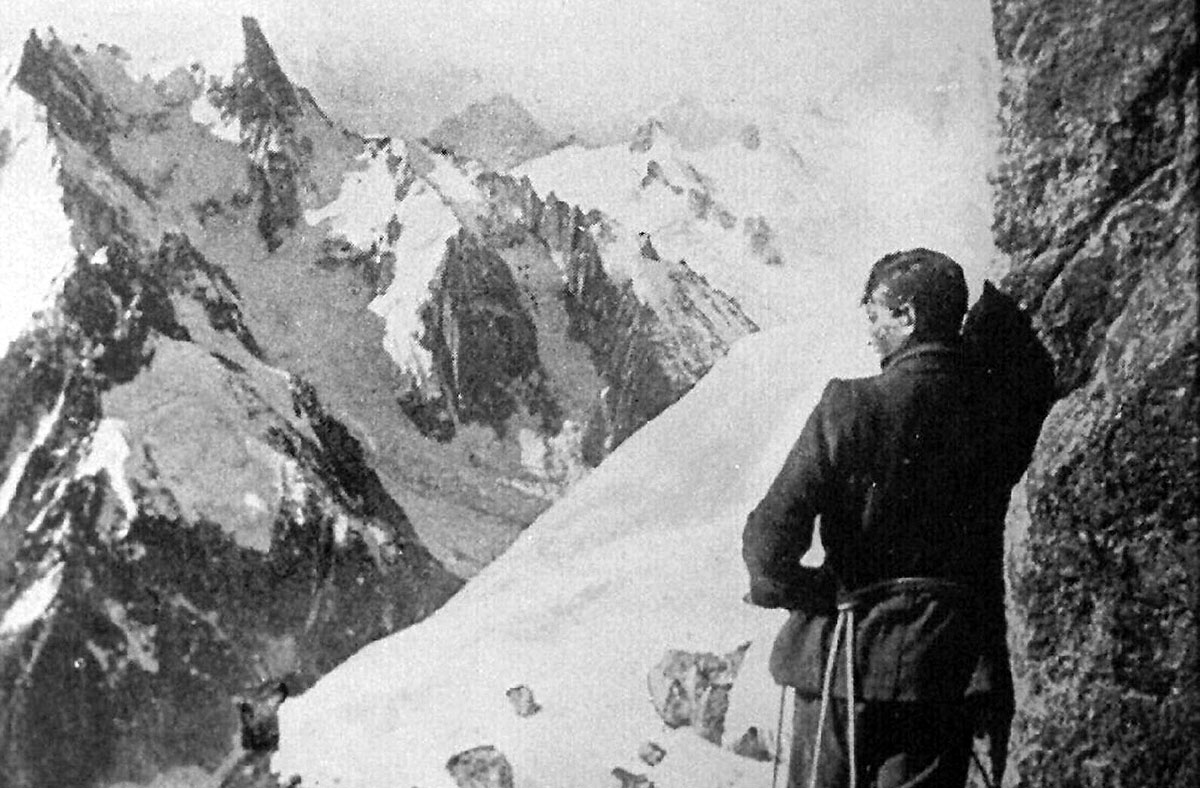

Serious attempts to climb the world’s highest mountain began in the 1920s, when the Dalai Lama allowed British climbers into Tibet. But the mountain defied them all, most famously George Mallory (below), who disappeared on its northeast ridge in 1924.

It would take another half a century, but on 29 May 1953, New Zealander Edmund Hillary and his Nepalese Sherpa Tenzing Norgay became the first people to stand on the summit of Everest. Their feat was not only a supreme individual achievement, but also stood testament to the technical capabilities of their support team. In particular, the two mountaineers relied heavily on their Rolex wristwatches, which they used to ration out their precious supplies of oxygen in one of the world’s most hostile environments.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Engineered for success

Although Mallory had been a highly competent mountaineer, he lacked support and, crucially, supplementary oxygen. By contrast, the 1953 expedition was meticulously planned by army colonel John Hunt, who took a military approach to conquering the peak.

It was a huge undertaking that included 350 porters, 20 Sherpa’s, and tons of supplies to support ten climbers. They trained for months at a base in Snowdon and travelled to the Himalayas a year before to prepare and test new equipment.

Teamed in pairs, each group was deemed capable of reaching the summit. Expedition members Tom Bourdillon, a former president of the Oxford Mountaineering Club, and Charles Evans, a brain surgeon, almost reached the summit first, but had to turn back when they ran out of oxygen in poor weather.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Hillary, 33, was highly experienced: it was his fourth Himalayan expedition in just over two years. Tenzing, 38, was a veteran of six previous attempts. Making an earlier start than Bourdillon and Evans and from a higher camp, Hillary and Tenzing reached Everest’s summit at 11.30am and spent 15 minutes at the top.

Hillary took the famous photograph of Tenzing holding the flags of the UK, Nepal and the United Nations with his 35mm Kodak Retina before the pair made their way down, leaving behind them a small silver crucifix and some food offerings to the mountain god.

Aside from careful planning, great skill and a little luck, the ascent owed its success to the equipment used by the expedition. The clothing was carefully adapted to the conditions: jackets were made from a lightweight and windproof cotton and nylon shell to protect them from the mountain’s fierce winds; climbing boots were lightweight custom high-altitude models made by The British Boot, Shoe & Allied Trade Research Association of Kettering; and aviator-style goggles with darkened glass lenses provided protection from UV rays and snow blindness.

Communication was another key component. The expedition used specially adapted Pye walkie-talkies that allowed the climbers to stay in contact as they made their way up the mountain from base camp. Their only drawback was that they weighed five pounds apiece and, because they used dry-cell batteries, had to be kept warm under clothing.

Every second counts

The most critical resource, however, was oxygen - and the Rolex watches they used to calculate how much of it they had left.

Their breathing apparatus, based on a design developed by Farnborough Royal Aircraft Establishment and made by a company that specialised in manufacturing high-altitude equipment for the aerospace industry, weighed 40lb and was designed to provide a total of 2,400 litres of oxygen, delivered at a flow rate selected by the climber.

This is where the Rolex watches proved invaluable, allowing the climbers to work out precisely what was left in their tanks. In the Death Zone a mistake would most likely prove fatal, so a dependable means of keeping time became a matter of life and death.

Testing times

Rolex had a longstanding interest in the world’s highest peak and had supplied watches to the first airmen to fly over the mountain in 1933. It produced the Rolex Oyster Everest to commemorate the feat.

Rolex wristwatches were also used by a 1952 Swiss mountaineering expedition, which got within about 800ft of the summit and pioneered a new route along the mountain’s southeast ridge, which Hillary and Norgay would follow a year later.

Norgay had also been a member of the Swiss expedition, and he wore the same Oyster Perpetual Datejust for both climbs. No watch had ever been subjected to such extremes of altitude, low pressure and low temperature, and the lessons learnt by Rolex led to the development of the Rolex Explorer, which went on sale soon afterwards - the descendants of which are still produced six decades later.

They, like every Rolex wristwatch, are subjected to a modern-day version of the extreme-weather test endured by those on the Everest expedition: today’s trials include 26 different drop tests, a 5,000G shock test and a spell in a pressurised water bath.

Even without this arsenal of procedures at their disposal, the Rolex engineers of the 1950s built a resilient product. Hunt, later Lord Hunt, confirmed that his watch was waterproof in snow, impervious to cold weather and didn’t need winding, a fiddly task in high wind and sub-zero temperatures - and too easily forgotten, with deadly consequences.

“We have indeed come to look upon Oyster Perpetuals as an important part of high climbing equipment,” he said.

Hillary himself felt the same. “Its accuracy is all one could desire,” he said.

-

Political cartoons for March 1

Political cartoons for March 1Cartoons Sunday’s political cartoons include the new normal, the sign of times, and more

-

Death in Lyon: the growing violence in French politics

Death in Lyon: the growing violence in French politicsTalking Point The death of Quentin Deranque has revealed the violence within the anti-fascist movement, and shown how the Right are ‘shamefully exploiting’ this tragedy

-

The row over student loans: is the system unfair?

The row over student loans: is the system unfair?The Explainer Millions of graduates have been left with hefty student loans, at high interest rates

-

South Africans are angry as Johannesburg faces a growing water crisis

South Africans are angry as Johannesburg faces a growing water crisisUnder the Radar This comes despite Johannesburg being Africa’s wealthiest city by GDP

-

Fugu Day: why Ghana’s traditional garment is having a renaissance

Fugu Day: why Ghana’s traditional garment is having a renaissanceUnder the Radar A centuries-old outfit is being rewoven into a statement of cultural pride – and defiance

-

Epstein files topple law CEO, roil UK government

Epstein files topple law CEO, roil UK governmentSpeed Read Peter Mandelson, Britain’s former ambassador to the US, is caught up in the scandal

-

Iran and US prepare to meet after skirmishes

Iran and US prepare to meet after skirmishesSpeed Read The incident comes amid heightened tensions in the Middle East

-

Israel retrieves final hostage’s body from Gaza

Israel retrieves final hostage’s body from GazaSpeed Read The 24-year-old police officer was killed during the initial Hamas attack

-

China’s Xi targets top general in growing purge

China’s Xi targets top general in growing purgeSpeed Read Zhang Youxia is being investigated over ‘grave violations’ of the law

-

Panama and Canada are negotiating over a crucial copper mine

Panama and Canada are negotiating over a crucial copper mineIn the Spotlight Panama is set to make a final decision on the mine this summer

-

Why Greenland’s natural resources are nearly impossible to mine

Why Greenland’s natural resources are nearly impossible to mineThe Explainer The country’s natural landscape makes the task extremely difficult