Why is Alabama pausing its executions?

Many states are struggling to carry out the death penalty

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

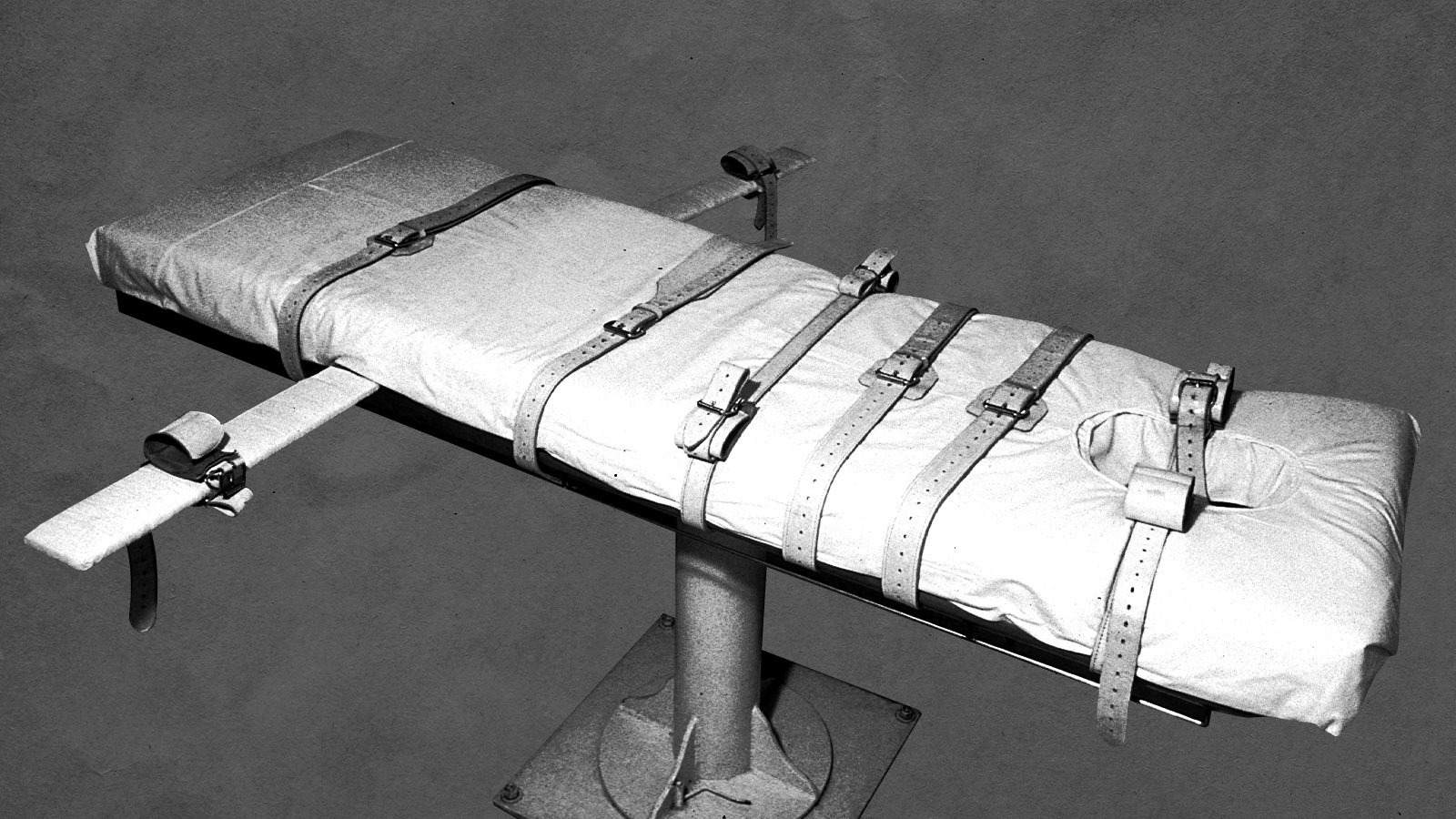

Alabama keeps botching the executions of condemned prisoners. Three times in recent years — and twice in just the last few months — the state has tried and failed to kill a condemned murderer. The most recent case happened in mid-November when officials had to call off the lethal injection execution of Kenneth Eugene Smith because they "couldn't find a suitable vein to inject the lethal drugs," The Associated Press reports.

Gov. Kay Ivey, a Republican, is calling a timeout. "For the sake of the victims and their families, we've got to get this right," she said on Monday, announcing a moratorium on Alabama executions until officials can determine what went wrong and how to improve the process.

But death penalty opponents don't trust the state to fix itself. "The Alabama Department of Corrections has a history of denying and bending the truth about its execution failures," Robert Dunham of the Death Penalty Information Center told Politico, "and it cannot be trusted to meaningfully investigate its own incompetence and wrongdoing." Why does Alabama keep messing up its executions? Is this just an Alabama problem? And what do failed executions mean for the death penalty in the United States? Here's everything you need to know:

Article continues belowThe Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

What went wrong in Alabama's executions?

The details of Alabama's lethal injection execution procedures "are a state secret," Ivana Hrynkiw reports for AL.com. But what we do know is that "perhaps no challenge has been greater than finding a vein to start the three-drug lethal injection mixture," Hrynkiw writes.

That was the case in the failed attempt to execute Kenneth Smith, and also in the botched execution of Alan Eugene Miller in September. It was the problem in Alabama's failed effort to kill Doyle Lee Hamm in 2018. (Hamm later died in prison, of complications from cancer.)

Why is that a problem?

Partly because it transforms what is supposed to be a relatively humane, controlled process into something chaotic and torturous. In Hamm's case, The New York Times reports, "an execution team struggled for nearly three hours, puncturing him at least 11 times in his legs, ankles, and groin and apparently injuring several organs before giving up."

Even when Alabama is successful with an execution, problems arise: After Joe Nathan James was executed in July, The Atlantic's Elizabeth Bruenig reported that an independent autopsy appeared to indicate that execution authorities made incisions into James' skin — a process known as "cutdown" — to find elusive veins in order to carry out the injection. It took three hours to complete the execution process. "James, it appeared, had suffered a long death," Bruenig writes. These problems have raised questions about whether Alabama's execution process violates the Constitution's ban on "cruel and unusual punishment."

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Are other states having similar issues?

Yes. "Over the course of just two days, Nov. 16 and 17, four people were supposed to die by lethal injection, and three of those executions were badly botched," writes Slate's Austin Sarat. Arizona's execution of Murray Hooper was — as in the Alabama cases — marked by problems finding Hooper's veins. "Can you believe this?" Hooper asked the viewing gallery while the prison team worked to find a vein. (In three Arizona executions this year, "the execution team struggled to insert intravenous needles," Sarat writes.)

Similarly, Texas authorities resorted to inserting a line into Stephen Barbee's neck during his execution: That's unusual — Barbee had a condition that made it impossible to fully extend his arms, which made it more difficult for authorities to place an IV line.

Why is this happening?

One reason: Ethics. The American Medical Association's ethics code forbids physicians from participating in executions. "This means corrections departments often rely on training members of their staff to serve on execution teams," Jimmy Jenkins writes at The Arizona Republic. That training is probably incomplete: Jenkins writes that it can take a month to train somebody on proper IV insertion, but Arizona prison officials are required to take only one IV training session before participating in an execution.

Similarly, AL.com's Hrynkiw reports that while Alabama's protocols are shrouded in secrecy, there is speculation that state's failed executions are happening "because of the training — or lack of — of the person responsible for setting up the [IV] line."

All of this takes place amid a larger backlash against the process of lethal injection. In recent years, states with the death penalty "had difficulty obtaining lethal injection drugs as pharmaceutical companies blocked their drugs from being used in executions," NPR reports. Tennessee Gov. Bill Lee, a Republican, paused his state's executions earlier this year over unresolved questions about the drug cocktail it uses. Some states — like Utah — have turned to other methods, like firing squads, as a result. And there is a backlash to the backlash: In announcing Alabama's moratorium, Gov. Kay Ivey blamed the "legal tactics and criminals hijacking the system" for the failed executions.

What's next?

Alabama has committed to a "top to bottom" review of its execution process, The Associated Press reports. "Everything is on the table — from our legal strategy in dealing with last-minute appeals, to how we train and prepare, to the order and timing of events on execution day, to the personnel and equipment involved," Corrections Commissioner John Hamm said in a statement. More than 160 prisoners on Alabama's death row — and the families of their victims — will be waiting to see the results.

Joel Mathis is a writer with 30 years of newspaper and online journalism experience. His work also regularly appears in National Geographic and The Kansas City Star. His awards include best online commentary at the Online News Association and (twice) at the City and Regional Magazine Association.