Why is heroin so cheap?

The drug that reportedly killed Philip Seymour Hoffman is inexpensive and readily available. Blame, in part, increased supply from Afghanistan.

This death of actor Philip Seymour Hoffman on Sunday was, above all, a personal loss for his family and friends and — as Scott Meslow and many others have noted — a huge artistic loss for the U.S. and the world. It is also a cautionary tale about the dangers of heroin. As if we needed another one.

The list of famous actors and musicians who have died too young from overdosing on heroin is long and sad. It includes Cory Monteith, River Phoenix, John Belushi, Janis Joplin, and dozens more. But for every boldface name whose life was destroyed by the drug there are hundreds of un-famous victims.

In the wake of Hoffman's death, NBC Nightly News has this story on the recent rise in heroin addiction:

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Law enforcement and addiction experts say the most common pattern is for people to move on to heroin from abuse of opioid prescription drugs like Vicodin and oxycodone (OxyContin). "It's not easy to get the opioid genie back into the bottle," Dr. Andrew Kolodny at the Phoenix House drug-treament center tells The New York Times. Heroin use has gone up as crackdowns have limited recreational access to prescription drugs, but as the Nightly News story notes, there is another draw: Heroin is cheaper.

A "stamp bag," like the kind Hoffman had in his apartment, typically costs about $10 on the street. In New York City, a major center of the U.S. heroin trade, a bag can cost $6, or as little as $4 if you buy in bulk. That's well within the reach of a whole bunch of people, both the curious novice and the hard-core addict.

By the time the drug makes its way up to New England, notes J. David Goodman at The New York Times, a bag can cost as much as $30 to $40. But use is still on the rise: Last month, Gov. Peter Shumlin (D-Vt.) spent his entire State of the State address talking about "a full-blown heroin crisis" in the Green Mountain State.

So why is heroin so relatively cheap? First, there's a lot of supply these days, thanks largely to an increase in opium poppy production in Afghanistan. Opium — from which heroin is derived — is grown in Southeast Asia (mainly Burma) and pockets of Central Europe and South America. Mexico is an increasingly large producer and exporter. But Afghanistan is by far the world's dominant supplier, as this map from ChartsBin shows:

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

And Afghanistan grew a record number of poppies in 2013, with opium production up an eye-popping 49 percent over 2012, Pentagon officials testified before a Senate committee in mid-January. Afghanistan's 5,500 tons of opium was about 90 percent of the world's supply last year. Not much of that opium makes it into the U.S. as heroin — only 4 percent of U.S. heroin came from Afghanistan last year, according to the DEA — but in a global market, a glut of product drives down prices. (Mexican heroin would probably cost more if Europe weren't being flooded with Afghan drugs, for example.)

On a more mundane level, unlike with prescription drugs and even generics, there are no patents in the heroin trade. No drugmaker can artificially inflate prices to recoup research and development costs.

Finally, heroin bags are cheap because once the drug arrives in New York and other distribution hubs, it's diluted with baking soda, lactose, or infant laxatives or other, cheaper drugs. The $10 stamp bags are about 25 percent pure heroine, say Drs. Anand Veeravagu and Robert M. Lober at The Daily Beast. That makes the drug cheaper, but also potentially deadlier.

The typical fatal overdose doesn't involve a new heroin user. "It most commonly involves an experienced long-term user in their 30s or older, who is using daily," say Veeravagu and Lober. "They have likely experienced multiple nonfatal overdoses prior to the final one."

Up to 22 percent of users will have a near-miss each year. Among other causes, they often won't know how much heroin they are taking, or what else they are taking along with it. Too much heroin or other opiate chokes the signals your brain sends out to tell your body to breathe. When you overdose on heroin and fall asleep, your body can simply stop breathing.

The deadliest additive at the moment appears to be fentanyl, a strong narcotic painkiller usually administered to cancer and other patients near the end of their life. In recent months, 22 people in the Pittsburgh area and 37 in Maryland died from fentanyl-cut heroin, and other states have reported small upticks. The last big surge was in 2005-06, when almost 1,000 people died nationwide from heroin mixed with fentanyl ultimately traced to one Mexican factory. There may be another influx of cheap fentanyl on the market now.

Fentanyl isn't only cheaper and 50 to 80 percent more powerful than heroin, it also prolongs the high. Users know this. "When someone knows that there are heroin bags that are killing people or making them overdose, then we know that those are the good bags," a 19-year-old recovering heroin addict named Andrew tells CNN. "That's the sick thing about addiction."

Low prices aren't good for discouraging people to use heroin, either. But interestingly, Matt Steinglass at The Economist proposes making heroin free, through state-run injection clinics, as they do in Switzerland and the Netherlands:

We don't know how to stop great artists from destroying themselves in one way or another. But we do have a good idea of how to stop more people from destroying themselves specifically with heroin injection, which has a higher fatality rate than most controlled substances:... Setting up safe injection rooms monitored by health-care staff, and — for registered addicts who cannot or will not comply with treatment regimes — providing heroin itself for free. [The Economist]

These so-called Heroin Assisted Treatment (HAT) systems sharply reduced heroin-related crimes, deaths, and HIV infections, Steinglass says. But "free government heroin tends to drive out private-sector providers," also, since it "gradually erodes the market for dealing heroin for profit; as they say in the tech world, you can't compete with free." He concludes:

Great artists and regular Joes will still hunger for mood-altering substances and will sometimes end up killing themselves, and we will continue to feel furious at them when they do. But we can channel that anger into finding ways to make their deaths less likely. [The Economist]

Peter has worked as a news and culture writer and editor at The Week since the site's launch in 2008. He covers politics, world affairs, religion and cultural currents. His journalism career began as a copy editor at a financial newswire and has included editorial positions at The New York Times Magazine, Facts on File, and Oregon State University.

-

Australia’s teen social media ban takes effect

Australia’s teen social media ban takes effectSpeed Read Kids under age 16 are now barred from platforms including YouTube, TikTok, Instagram, Facebook, Snapchat and Reddit

-

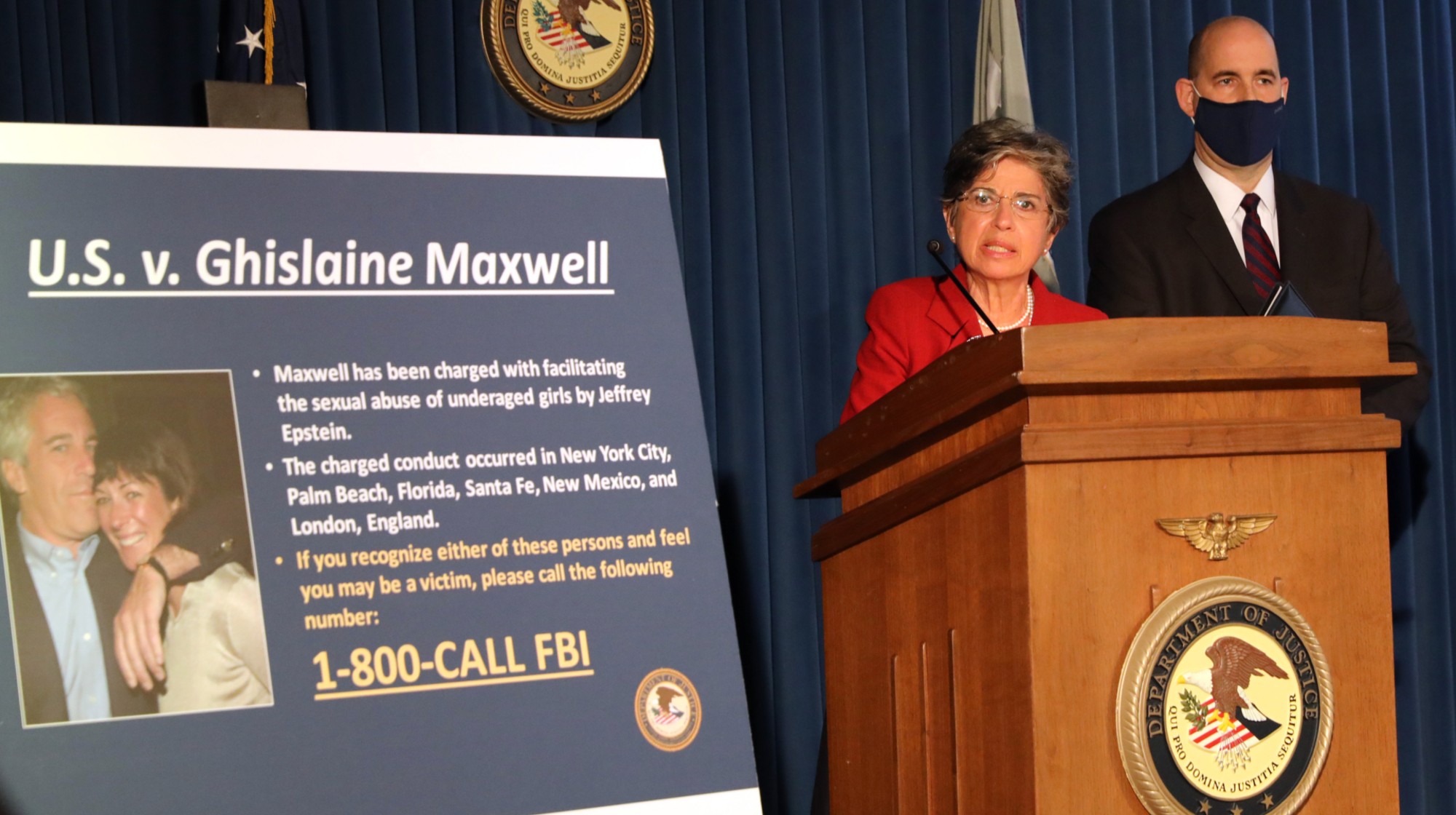

Judge orders release of Ghislaine Maxwell records

Judge orders release of Ghislaine Maxwell recordsSpeed Read The grand jury records from the 2019 prosecution of convicted sex offender Jeffrey Epstein will be made public

-

Miami elects first Democratic mayor in 28 years

Miami elects first Democratic mayor in 28 yearsSpeed Read Eileen Higgins, Miami’s first woman mayor, focused on affordability and Trump’s immigration crackdown in her campaign