Is it no longer OK to buy your daughter a doll?

'Tis the season for anxious parenting

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

We should be living in shopping's age of ease. In a matter of minutes you can find the best product for the best price; two days later it's at your door. But this era also happens to be one of increasing awareness about the social and environmental impact of the goods we buy. All that time we've gained through technology? We end up spending it in conscientious deliberation.

Thanks to the feminist revival of the past half-decade more and more parents now hesitate to buy their daughters a doll or sons an action figure. In Australia, activists are calling for a "No Gender December;" in the UK a campaign called "Let Toys Be Toys" is pushing for gender-neutral toys; in Sweden some toy stores are now gender neutral; and here in the States resistance to the pink aisle is growing louder and louder.

There are plenty of reasons to support such efforts.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Studies show that toys associated with girls are more likely to be related to appearance and serving others, while those associated with boys are more likely to be related to building things and competition.

Also, the divide between "boy" toys and "girl" toys has gotten wider. In the 1970s, toys were actually less gendered than they are today, something experts attribute to a shift in marketing strategies. Meanwhile, a scientific study on primates suggests that the only real difference between the preferences of boys and girls is that boys like wheeled objects more than girls. That's it.

The problem is, anyone who has spent time around kids knows that — nurture, nature, whatever — boys and girls want what they want. And they tend to want things that are at least a little gender-specific.

Buy dolls for boys, as the second-wave "Free to Be You and Me" generation did? Ban dolls for girls, as many enlightened women of today consider doing? Or opt exclusively for more gender-neutral toys like a doctor's set or building blocks?

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Fortunately for all the harried parents out there, the answer is pretty simple: mix things up. Don't deny girls the pinkest, glitteriest princess dress-up kit on the shelf, and don't deny boys that ninja sword. Just also make sure to get them a few gender neutral things as well, along with a few "boy" things for girls and "girl" things for boys.

This is the advice of Lise Eliot, neuroscientist and the author of the book Pink Brain, Blue Brain, which looks at how gender differences evolve in children and the small role biology plays in this.

"I wish parents would stop beating themselves up about this," Elliot said. "The trick is to have a huge variety of toys things, and to never call anything a 'boy' toy or 'girl' toy. Don't endorse the labeling," Eliot said.

Eliot explained that kids are hardwired in a way that makes them, at least in the late preschool and early elementary school years, take on very unambiguous ideas about gender. Boys want to be boys and girls want to be girls. There is no use in trying to ignore ideas of gender altogether because kids will pick them up elsewhere. The key, then, isn't to get them to stop paying attention to the fact that they are a boy or a girl, but to encourage them to view these roles with as much fluidity as possible.

Somewhat surprisingly, we should be looking at girls as a model. While much of the hysteria surrounding gendered toys has been directed at the pink aisle, there has actually been more of a shift in girls willing to play with "boy" toys in recent decades than vice versa. Today, there is much less stigma for girls who play with tool kits or wear the color blue than there is for boys who want to twirl around in a tutu or braid a girl's hair.

"There's still a strong fear of femininity in boys," Eliot explained, one that affects them in the classroom as well. Boys are still underperforming girls in reading and writing, while girls have largely caught up to boys in math and sciences. This at least in some part a result of how parents are more likely to push girls to engage in more verbal forms of play and reading than boys, because a boy being unable to express himself is more tolerated in our culture than a girl.

Which brings us to the final point. Toys aren't just things we buy for our kids to distract them, although they certainly sometimes fill that role; they also help them explore different identities and understand how the world works. Parents shouldn't just buy toys, but also be the ones to model how that toy can be played with and by whom. Daughter wants that doll? Fine. But then maybe dad is the one to sit down and figure out what dress she should wear for her big date.

Elissa Strauss writes about the intersection of gender and culture for TheWeek.com. She also writes regularly for Elle.com and the Jewish Daily Forward, where she is a weekly columnist.

-

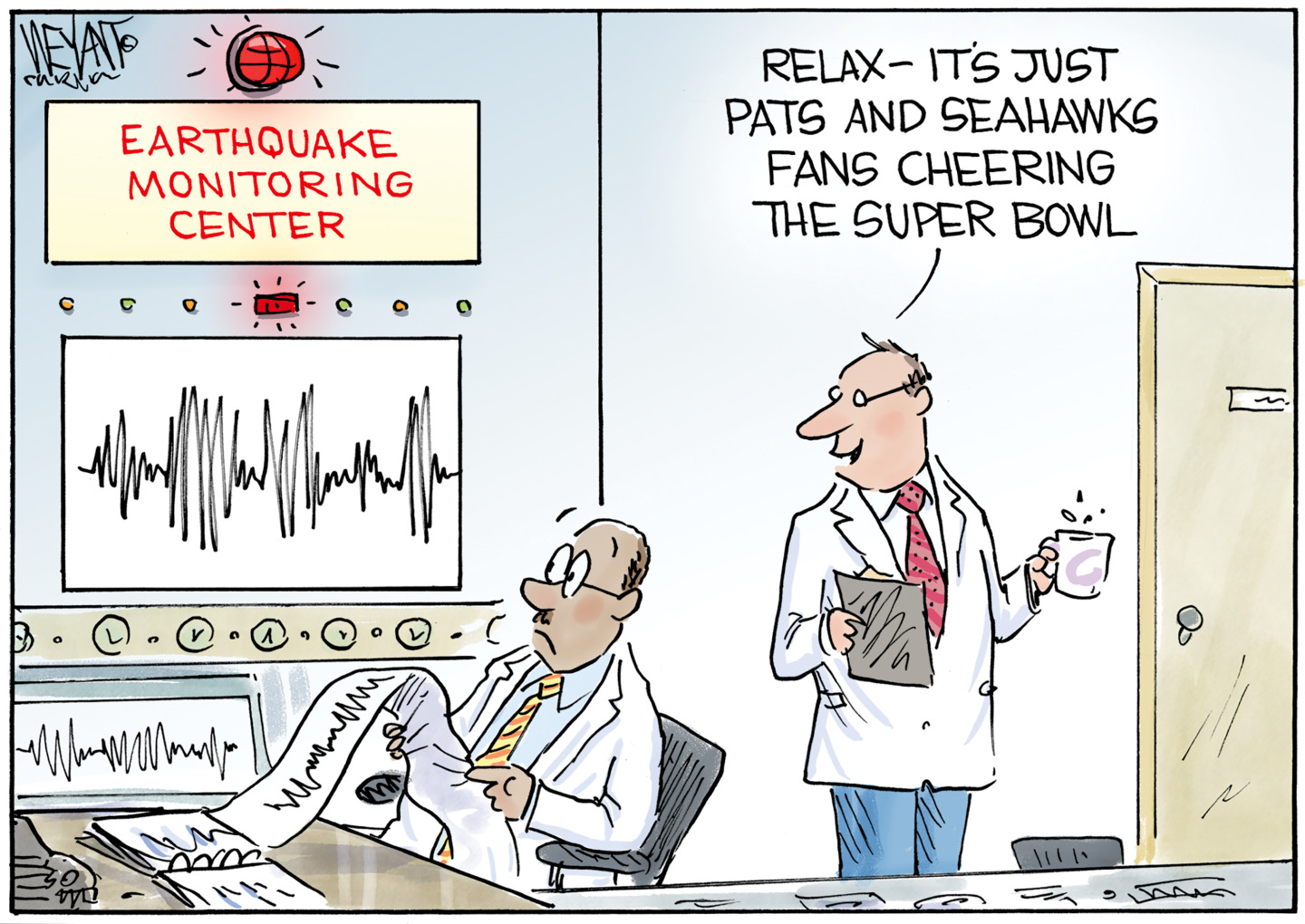

Political cartoons for February 7

Political cartoons for February 7Cartoons Saturday’s political cartoons include an earthquake warning, Washington Post Mortem, and more

-

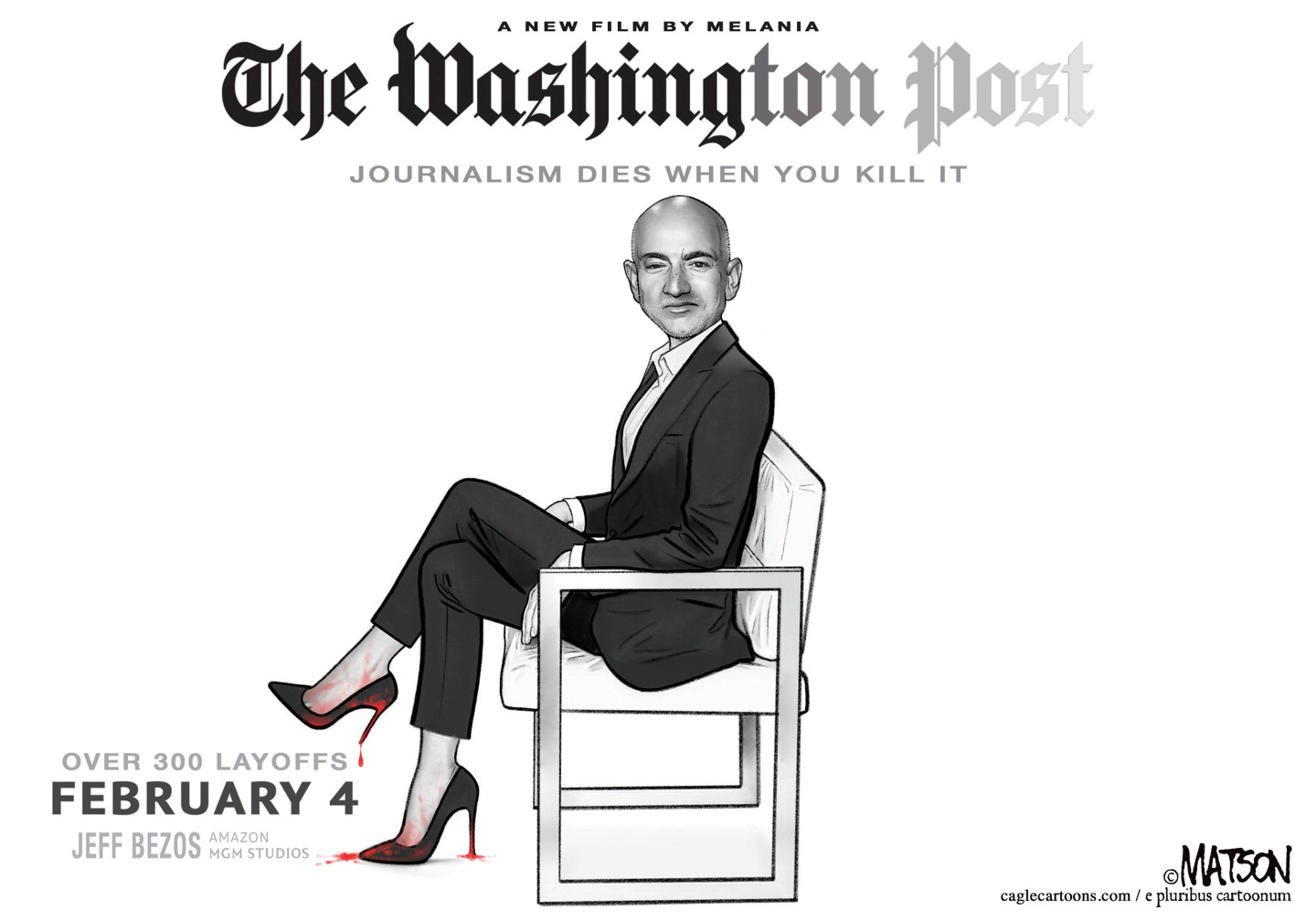

5 cinematic cartoons about Bezos betting big on 'Melania'

5 cinematic cartoons about Bezos betting big on 'Melania'Cartoons Artists take on a girlboss, a fetching newspaper, and more

-

The fall of the generals: China’s military purge

The fall of the generals: China’s military purgeIn the Spotlight Xi Jinping’s extraordinary removal of senior general proves that no-one is safe from anti-corruption drive that has investigated millions