Girls on Film: The immortal Mike Nichols

The legendary director, who died this week at 83, leaves one of Hollywood's most powerful and enduring legacies behind

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

It's impossible to overstate the reach of Mike Nichols, who died this week at the age of 83. He made multiple award-winning films; was half of one of history's most influential comedy acts alongside Elaine May; mentored many of the talents we know and love today; and offered work so thoughtfully human that his impact extends well beyond the reach of film. The Graduate earned Nichols his only Golden Globe and Oscar wins, but he is one of the few people in history to have won an Emmy, Grammy, Oscar, and Tony, and his films influenced the craft more than many of his contemporaries.

Like many, I was introduced to Nichols through The Graduate, though I was familiar with its legacy long before I actually saw it. Simon and Garfunkel sang of Mrs. Robinson's affair. The film's trivia found its way onto Survivor. Everyone kept whispering about plastics. Just to mention the film's title sent many into vocal, effusive praise.

Almost 50 years later, The Graduate still thrives as a mix of art and entertainment. It's still easy to melt into Simon and Garfunkel's softly melancholic soundtrack, to ponder the gender politics, to get seduced by Mrs. Robinson, to be swept up in the charismatic ennui of Benjamin Braddock. The viewer evolves with the film, from Ben's clueless youth to Mrs. Robinson's weathered maturity.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

At 36, Nichols offered a film that transcended the boundaries of his own experience. There are many reasons for his success, but there is one that allowed him a level of reverence rarely shown classical male filmmakers: he saw art as a reflection of the lives of men and women.

Nichols was not a "woman's director" like Rodrigo Garcia. Nichols simply embraced female characters and stories with the same fervency of male stories, often side-by-side. As Wesley Morris aptly noted at Grantland, "He was drawn to works about men, women, and their respective and overlapping natures: what makes a man a man, a woman a woman, and a couple a couple."

By including women in his theatrical and cinematic explorations, Nichols offered an unparalleled filmography in which women were genuinely represented. He took recognizable tropes — say, the discontent of the aimless housewife — and imbued them with a new depth and complexity. Women weren't just a narrative construct in a male journey; they were dynamic participants in life.

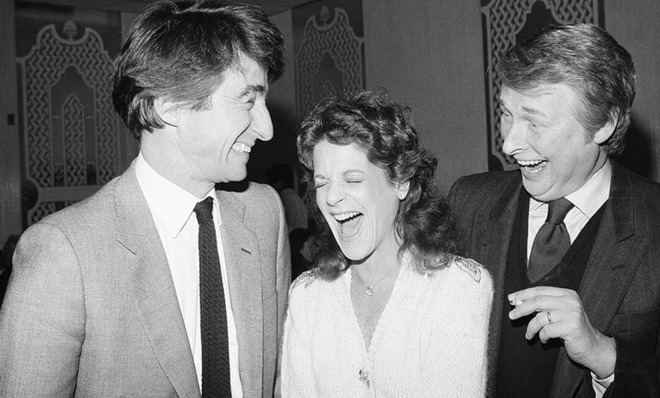

That Nichols' first collaborator was a woman — and one who easily embraced and countered his wit — is telling. He met Elaine May in Chicago, with their keen first words to each other paving the path for a brief but revolutionary rise as satirists who influenced everyone from Lily Tomlin to Steve Martin to Saturday Night Live.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

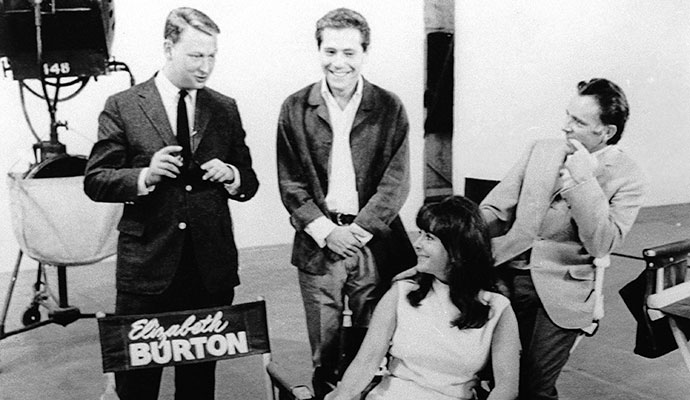

Nichols' reputation exploded with his freshman feature, Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf? There was no learning curve. He pulled new depths out of one of the industry's biggest icons, and Elizabeth Taylor went on to win her final Best Actress Oscar for playing one half of a bitter and abusive couple.

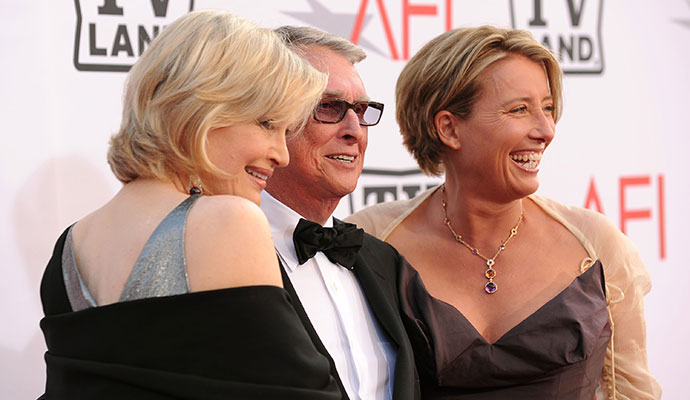

His ability to craft and capture stunning performances from women knew no bounds, from the most indelible icons to the freshest faces. Nichols coaxed Oscar-nominated and Oscar-winning performances out of 12 women, plus Golden Globes, Emmy, and Tony accolades for his actresses. He brought Lillian Hellman's The Little Foxes to life. He reunited with May on the scripts for The Birdcage and Primary Colors, and with star Emma Thompson on Wit. He brought the words of Carole Eastman and Carrie Fisher to life, and shot Gilda Radner's 1980 comedy film Gilda Live. His collaborations with Nora Ephron kickstarted her movie career with the one-two punch of Silkwood and Heartburn.

In an industry that needs men to mentor and foster female talent, Nichols always led the charge. "There was that great ability in Mike to encourage people to do their best," Carly Simon noted after his passing. As the years went on, he discovered and mentored Whoopi Goldberg, boosted the careers of Julie Andrews and Carol Burnett, and offered the platform that won Sara Ramirez a Tony.

The sheer number of essential female voices that were aided by Nichols is astounding. Nichols saw the acting talent in Cher that would ultimately lead to her Oscar-winning performance in Moonstruck. This is the director who took a woman known for playing different versions of "Julia Roberts," and made her the darkly compelling Anna in Closer, swapping that trademarked smile for a stunningly quiet and thoughtful performance no other director has come close to matching.

Improvisation trained him as a director. As he told Nora Ephron, improvisation "teaches you what a scene is made of — you know, what needs to happen. See, I think the audience asks the question, 'Why are you telling me this?' and improvisation teaches you that you must answer it. There must be a specific answer." His art wasn't about fostering his voice and shaking his head at those who didn't "get" his vision — it was about embracing the needs of the audience he was courting.

Some have noted that Nichols was never seen as an auteur. He didn't have a particular visual style, and he told all manner of stories. But Nichols was an auteur of life and humanity, from the darkness of drama to the light touch of satire. He never pushed a particular and idiosyncratic slice of life. In an industry that thrives on ego and eccentricity, Mike Nichols was a creator who worked outside his own vision. The audience was never the enemy, and women were never an untouchable force from another planet. Nichols thrived because he looked beyond himself.

Girls on Film is a weekly column focusing on women and cinema. It can be found at TheWeek.com every Friday morning. And be sure to follow the Girls on Film Twitter feed for additional femme-con.

Monika Bartyzel is a freelance writer and creator of Girls on Film, a weekly look at femme-centric film news and concerns, now appearing at TheWeek.com. Her work has been published on sites including The Atlantic, Movies.com, Moviefone, Collider, and the now-defunct Cinematical, where she was a lead writer and assignment editor.

-

Antonia Romeo and Whitehall’s women problem

Antonia Romeo and Whitehall’s women problemThe Explainer Before her appointment as cabinet secretary, commentators said hostile briefings and vetting concerns were evidence of ‘sexist, misogynistic culture’ in No. 10

-

Local elections 2026: where are they and who is expected to win?

Local elections 2026: where are they and who is expected to win?The Explainer Labour is braced for heavy losses and U-turn on postponing some council elections hasn’t helped the party’s prospects

-

6 of the world’s most accessible destinations

6 of the world’s most accessible destinationsThe Week Recommends Experience all of Berlin, Singapore and Sydney