The new film that's making Mexican politicians sweat

When Luis Estrada makes a movie, Mexican politicians know they're in trouble

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

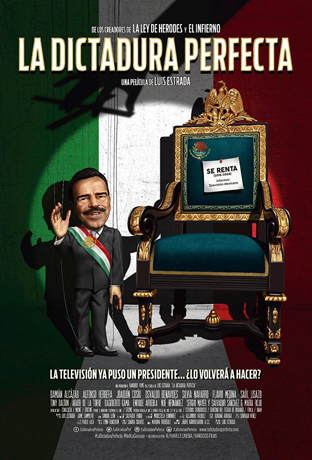

As if the disappearance of 43 students, the discovery of mass graves, and a federal investigation into a possible mass execution by soldiers weren't enough, Mexican President Enrique Peña Nieto now has another thing to worry about. La Dictadura Perfecta (The Perfect Dictatorship) premiered yesterday in over 2,500 theaters in Mexico. It's the latest film from Luis Estrada. And when Estrada makes a movie, Mexican politicians know they're in trouble.

Estrada is the most rebellious and controversial filmmaker in Mexico. He is a master of political satire, a merciless critic of politics and society, and an artist who loves making his countrymen uncomfortable.

His latest film is part three of a trilogy that began in 2000 with La Ley de Herodes (Herod's Law), a film that ridiculed the corruption and nepotism that characterized the Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI), which ruled Mexico as a one-party state between 1929 and 2000. (The PRI is now back in power, with the Nieto presidency.) His follow-up, 2010′s El Infierno (Hell), was an extremely violent black comedy about Mexico's bloody drug war.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

And now there's La Dictadura Perfecta, and once again Estrada doesn't pull punches. The film depicts the perverted relationship between monopolistic media conglomerates and Mexico's ruling political caste. In the film, a corrupt and murderous governor employs the services of a powerful television station to manipulate the news into diverting attention from a bribery scandal.

The movie makes a direct allusion to Televisa, the Mexican media giant that has been accused of selling positive coverage to Mexican politicians. There is also a fictional president in the story who strongly resembles Nieto and who is depicted as a mere puppet of the fictional media barons. Buzz for the movie has been building in recent weeks — a trailer for the film got 2 million views in just a few days after it was released in August.

(Bandidos Films)

There has never been much love lost between Mexico's ruling class and the renegade filmmaker. In 2000, the Mexican government attempted to block his first film from being distributed. Ten years later, El Infierno was heavily criticized by the government of then president Felipe Calderón. Vocativ spoke to Estrada about fact and fiction in Mexican politics and the possible fallout from his new film.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

How does La Dictadura Perfecta relate to Mexican reality?

Exaggeration is part of my personality, and the movie is satirical, so obviously I took some liberties in how I present the story. But if you look at recent events in Mexico, at the disappearance and possible mass murder of dozens of students in Guerrero state, there is very little difference between fact and fiction. The governor in my movie, Carmelo Vargas, is a fictitious monster, but the governor of Guerrero state is real. And the way he consistently tried to wash his hands of the whole affair with the missing students is appalling and unbelievably cynical.

What role does the Mexican media play in such incidents?

Mexico is governed by a rich and privileged ruling class, which has a perverted relationship with the media. Commercial television in Mexico was founded by people with strong ties to the current ruling party. They will show to the public what they find relevant, which is their right, but they will go far to defend their interests and relationships. Unfortunately, a large share of the Mexican population lives in poverty and has little access to information. They can be easily manipulated.

Is it anger about such things that drives you to make movies?

Anger is only part of it. It's also genuine concern about what's happening in my country. Mexico is my country, my children are growing up here, in a society rife with violence, corruption, impunity and abuse of power. Things are very bad in Mexico right now, so bad I sometimes can't wrap my head around it. I'm not an activist, but rather a concerned citizen who expresses those concerns in film.

Iframe Code

There was some public backlash after the first two movies. Has there been any of that with your new film?

Surprisingly, a lot of young people who attended preliminary showings at universities told me that the movie is bad for Mexico's image, that I shouldn't depict the country as being violent and corrupt. I say to them: Worry about the state of the country, rather than the image it has abroad. Politically, things have been easier. La Dictadura Perfecta will be widely distributed in Mexican theaters, and I have even been invited to show it at Congress next week.

Students have gone missing, mass graves are found everywhere, soldiers are accused of executing civilians. Why do you think more Mexicans aren't speaking out about recent events?

Civil society in Mexico can be blamed for the fact that things don't change. There has been a strong emotional reaction to the disappearance of the students from certain sectors of society, but I still feel that a large part of society reacts far too passively. And I unfortunately don't think that the anger will last either. It hardly ever does in Mexico. I wouldn't be able to tell you why — I don't understand it myself.

This story was originally published on Vocativ.com: The new film that's making Mexican politicians sweat

More from Vocativ...