Girls on Film: There is no 'true' version of Gone Girl

Gillian Flynn's novel is built on subjective truths — and David Fincher's new film is just another layer of the story

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Spoiler warning: This story will discuss the twists in both the book and film versions of Gone Girl.

In Gillian Flynn's Gone Girl, truth is many things: empirical, palpable, malleable, confessional, pure, and ugly. Revelations are framed as the truth, half-truths, and untruths. As it twists and turns, the story offers "truths" and then tears them right back down, provoking a never-ending sense of uneasiness.

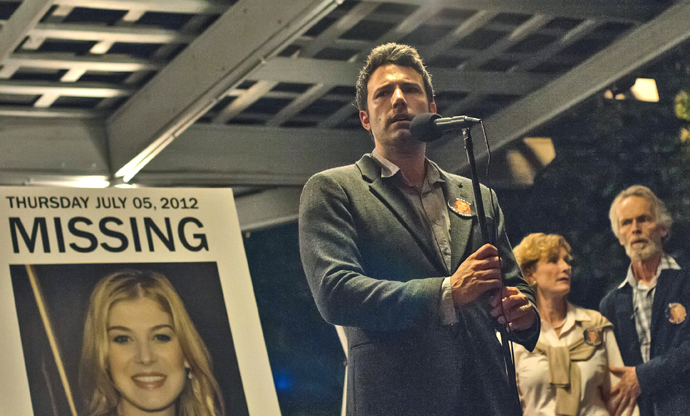

Gone Girl is the story of a missing woman, and the man who seems ever-guiltier of committing the crime that took her away. On her fifth wedding anniversary with Nick (Ben Affleck), Amy Dunne (Rosamund Pike) disappears, and her disappearance becomes a national media event. She's everything the media loves: a beautiful blonde with a bright smile, and a minor celebrity after serving as the inspiration of her parents' "Amazing Amy" series of children's books. Nick, meanwhile, is everything a leading suspect can be: charming (if not a bit too affable), prone to fibbing, and incapable of convincing anyone that he's wholly innocent.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

In Gone Girl, attention switches from the heartfelt search for Amy to the spin everyone puts on their version of the story. Nick must create a story to appear innocent. The police must create a story to explain their evidence. The media must create a story to tantalize their audience. The lawyer must create a story for his client. The public must create a story to feed their curiosity. And Amy is, literally, a woman living through a story — as both an idealized "Amazing Amy" and as a woman who, after her disappearance, exists only in the record of her friends, family, and her own journal of her life.

Each of these stories is volatile. In most narratives, a story becomes more truthful with each discovery. In Gone Girl, however, evidence just fuels seemingly endless crescendos that threaten to drown out the sound of the truth.

As a film, Gone Girl stays loyal to the beats of the story while removing some of the keen commentary that made the novel so compelling. But taken as a piece with the novel, the film works because director David Fincher's approach adds yet another agenda-fueled person to the list of those crafting their version of the story.

On paper, Flynn relishes in female villains. As she told The Guardian last year, "the one thing that really frustrates me is this idea that women are innately good, innately nurturing. In literature, they can be dismissably bad — trampy, vampy, bitchy types — but there's still a big pushback against the idea that women can be just pragmatically evil, bad, and selfish."

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Flynn's mourning over the lack of female villains has led her to fill her novels with them, which grew especially problematic for Flynn in Gone Girl, where Amy manipulates the very systems struggling for real-life public legitimacy. Amy uses her womanhood to manipulate men, happily using public support of rape victims to fuel her own false accusations. In a context-free world, her actions are just evil; in the actual world, they blur into a well-trod narrative of untrustworthy womanhood.

But Flynn uses Gone Girl to undermine flimsy notions of womanhood, and nowhere more bluntly than in her exploration of the Nice Guy and Cool Girl. Nick's "Nice Guy" persona gives little thought to things, follows his whims, and fails at Amy's yearly scavenger hunts because he doesn't even pay attention to the aspects of their relationship Amy holds dear. He's a man who is happy to lazily enjoy his "Cool Girl" wife, never realizing it's an act. As Amy bitterly notes:

"Being the Cool Girl means I am a hot, brilliant, funny woman who adores football, poker, dirty jokes, and burping, who plays video games, drinks cheap beer, loves threesomes and anal sex, and jams hot dogs and hamburgers into her mouth like she's hosting the world's biggest culinary gang bang while somehow maintaining a size 2, because Cool Girls are above all hot. Hot and understanding. Cool Girls never get angry; they only smile in a chagrined, loving manner and let their men do whatever they want. Go ahead, shit on me, I don't mind, I'm the Cool Girl."

Amy's Cool Girl rarely nags. She gives up her life to move back to Nick's hometown, lives without her friends, and uses the last of her money to buy him a bar. Her wickedness is jump-started when he betrays her by beginning an affair. Amy is a truly awful person, but she only acts that way when she feels deceived. Nick's Nice Guy, meanwhile, exemplifies the banality of evil. Where Amy embodies malevolent hatred, Nick's actions are thoughtlessly immoral.

The film dumbs down this message to a single point: Don't trust Amazing Amy. In the film, Nick is the Nice Guy victim. The textual morsels used to make readers doubt his innocence become examples of his victimization. He awkwardly smiles for an instant, and the media creates a story around it. A woman catches him off-guard for a picture and ignores his pleas to delete it. The nosy neighbor who smears him is obviously unhinged.

Rather than skewering the Nice Guy myth, as Flynn did in her novel by accentuating Nick's many flaws, Fincher's film finds comfort in them. Taken from a female author, and placed into the hands of a male actor and director, Nick is transformed into an actual Nice Guy. Sure, he might have cheated on his wife and acted lazy now and then — but he just can't help it. He doesn’t know how to act because his movements have never been so microscopically judged.

Fortunately, that kind of free interpretation is at the heart of Gone Girl anyway. Truth is relative, and each storyteller switches it for their own ends, which leads to any number of readings. There's nothing as neat as victim and perpetrator in Flynn's and Fincher's worlds. As in Gone Girl itself, each storyteller merely spin the tales in a way they can understand.

Girls on Film is a weekly column focusing on women and cinema. It can be found at TheWeek.com every Friday morning. And be sure to follow the Girls on Film Twitter feed for additional femme-con.

Monika Bartyzel is a freelance writer and creator of Girls on Film, a weekly look at femme-centric film news and concerns, now appearing at TheWeek.com. Her work has been published on sites including The Atlantic, Movies.com, Moviefone, Collider, and the now-defunct Cinematical, where she was a lead writer and assignment editor.