Can we lead spiritually fulfilling lives without religion?

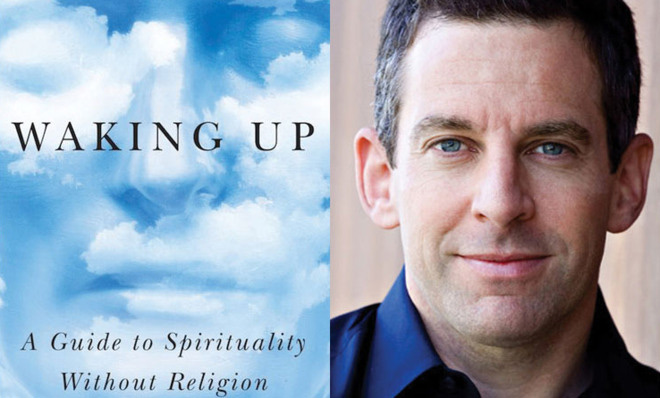

Sam Harris' new book, Waking Up, posits that we can. Too bad he has his wires all crossed.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Normally when I read a book by Sam Harris, I have to restrain the urge to hurl it into the trash.

The End of Faith (2004) launched the New Atheist movement by ignorantly distorting, simplifying, and insulting all three monotheistic religions, while also denouncing, in flagrantly illiberal terms, "the very ideal of religious tolerance."

The Moral Landscape (2010) cavalierly dismissed the broad range of problems and proposals put forward in the philosophical and theological traditions of the West in favor of a facile, desiccated form of scientistic utilitarianism.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

But Harris' new book, Waking Up: A Guide to Spirituality Without Religion, is different. It's not exactly good. But its intellectual offenses are marginally less egregious than what I've come to expect from the author. (How will that work for a blurb?)

Harris has long stood out among the New Atheists in confessing to nontheistic spiritual experiences and longings that have led him to undertake frequent lengthy meditative retreats and to experiment with psychedelic drugs. His new book is an attempt to justify these experiences and longings in terms that will win the respect of neuroscientists. (Harris has a Ph.D. in the field.) The result is an unusual synthesis of pop science with a self-help guide to Eastern mysticism.

Harris' starting point is a vaguely felt dissatisfaction that many readers will recognize. Our lives often seem to be exactly what Thomas Hobbes described them to be in the mid-17th century: a "perpetual and restless desire of power after power, that ceaseth only in death." We strive for one goal as a means to reaching another, which in turn propels us onto a third, and on we go through life, careening from one object of desire to the next, with no final resting point or experience of genuine fulfillment or contentment until we finally arrive at the only true state of rest: annihilation.

"Is there more to life than this?" Harris asks. "Might it be possible to feel much better (in every sense of better) than one tends to feel? Is it possible to find lasting fulfillment despite the inevitability of change?" These are important, serious questions, and Harris is right to suggest that "spiritual life begins with a suspicion that the answer to such questions could well be 'yes.'"

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

There's just one problem: Most people in the Western world have sought spiritual fulfillment through Judeo-Christian monotheism, which Harris considers to be pernicious, unscientific claptrap. That leaves the option of Eastern spirituality, though Harris can't restrain himself from taking plenty of swipes at Buddhist and Hindu gurus for saying their own scientifically ludicrous things.

Yet Harris nonetheless believes that, unlike Judaism, Christianity, or Islam, the meditative strands of Buddhism and Hinduism contain a cluster of empirically verifiable truths about the human mind and happiness. Specifically, these meditative traditions aim for and can lead properly disciplined individuals toward an experience of "mindfulness" and "self-transcendence," by which Harris means the dissolution of our very sense of selfhood, a loss of the feeling of "I" that he insists is the root cause of our psychic restlessness and unhappiness.

But rather than proceeding directly to an explication of Eastern spirituality, Harris feels the need to prove (to himself? to skeptical colleagues, real and imagined?) that his advocacy of "spirituality without religion" isn't tantamount to hocking silly, unscientific mumbo jumbo. The practice of seeking fulfillment in the meditative dissolution of the self, Harris very much wants to demonstrate, is perfectly consonant with and even follows with perfect reasonableness from what neuroscientists have discovered about the brain.

That's why the core of the book consists of a series of long explications of various neuroscientific experiments and theories. Fundamental components of consciousness are dispersed throughout both hemispheres of the brain, Harris informs us. When the nerve bundles known as the corpus callosum, which bind the two hemispheres together and facilitate their complex interaction, are severed in a procedure that can be used to treat epileptic seizures, the results are bizarre.

Though the split-brain patients appear normal, under "experimental conditions" scientists have discovered that the hemispheres display "an altogether functional independence, including separate memories, learning processes, behavioral intentions, and — it seems all but certain — centers of conscious experience."

Someone with a split brain might be able to "draw incompatible figures simultaneously with the right and left hands," like "two artists working in parallel." A patient's left and right hands "sometimes engage in a tug-of-war over an object or sabotage each other's work." Experiments also seem to show that the two hemispheres can have independent thoughts, opinions, and perhaps even independent forms of consciousness. (Though the right hemisphere's ability to express its conscious intentions is hampered by the fact that the most advanced language skills are rooted in the left hemisphere.)

This and the other summaries of scientific research in the book are fascinating in the way that good pop science writing often is — by simplifying and explaining complicated, technical work in a compelling, thought-provoking way to a generalist audience.

But Harris goes far beyond typical science journalism in concluding from this research that the nearly universal human experience of unified consciousness and selfhood "is an illusion," that coming to recognize and accept its illusory status is a necessary step on the road to "waking up" into a more fulfilling life of self-dissolution, and that meditative practices derived from Eastern spirituality are the best methods of achieving this selfless state of mind.

Let's just say that I'm skeptical. The meditative dissolution of the self contained in certain strands of Buddhism and Hinduism is one of civilization's great responses to the riddle of human experience and happiness. But the findings of neuroscience don't verify it in the way that Harris thinks they do. And Harris likewise gives no indication of having seriously pondered the Western (philosophical and psychological) alternatives to embracing Eastern spirituality. He's thus a highly unreliable guide to the subject of his own book.

Harris' accounts of these experiments are interesting and more than a little creepy (in a sort of B-movie horror flick kind of way). But why should these changes in human perception, produced by meddling with the normal functioning of the brain, serve as a guide to the nature of the mind? Harris doesn't tell us. He just assumes it.

But that's not good enough. Aristotle and his many centuries of successors took a different and far more sensible approach: We can best discover the nature of a being by observing it in its state of greatest flourishing. So to grasp the nature of the human mind, we should observe the most highly developed mind we can find, and certainly not treat as normative the way a mind behaves when it has been handicapped by natural defect or an injury imposed by surgical intervention. To take the latter approach is like studying the nature of human motion by observing the mobility of a person hampered by a broken femur.

The pursuit of self-dissolution through meditation may very well be a vital path to human flourishing, but recording the experiences of people whose brains have been sliced in two can't establish it.

Then there's the little matter of the soul. Harris irritatedly dismisses the concept at several points in the book, treating it as a foolish holdover from empirically discredited theological and scriptural traditions. But the Western philosophical tradition stretching from Socrates through the early modern period didn't rely on revelation in presuming that human beings have souls. These philosophers were merely describing the seat of the unity of consciousness and an individual's motive force (animus/anima) in pursuing ends or goals. (Many philosophers followed Plato in suggesting that the soul must be immortal, but not all did. And nothing in their speculations about the nature of the soul depends on believing that the soul survives the death of the body.)

The Western philosophical focus on the soul is significant for Harris's project because it points to a fundamental disagreement between the West and the version of Eastern spirituality that Harris champions. For many Western philosophers, the question of human flourishing can't be disentangled from questions about what the human soul is seeking in its anxious (seemingly endless, sometimes miserable) striving for one damn thing after another. As Harris understands it, the Eastern answer to this striving is to counsel self-erasure — the purgation of desires and thoughts from the mind altogether. That is indeed one option.

But the Western response is to suggest that at least some people — philosophers, saints, sages, mystics — are capable of getting their souls in order without purging them, of living worthwhile lives in active pursuit of the true satisfaction of the soul's truest desires.

If that sounds too much like theological gobbledygook, the West contains another, more modern option — the philosophical reflection on and psychological study of the self. As Jerrold Seigel explains in his definitive history of The Idea of the Self, a long series of philosophers and psychologists from the 17th century down to the present day have developed a range of concepts for understanding selfhood. At their most elaborate, they combine at least three dimensions: a range of desires rooted in the body; a tendency toward communal interaction with and relation to others; and a capacity for standing back from the world and oneself in a state of dispassionate reflection or observation.

Some thinkers have emphasized (or overemphasized) one of these dimensions, but others (like Sigmund Freud at his best) have explored the complicated ways that these three dimensions of selfhood can and often do subvert each other, fostering the kind of discontent that Harris treats as a human given. Serious meditation is one legitimate way of responding to this discontent. But so is the kind of self-analysis (talk therapy) that Freud pioneered in often fruitful, sometimes questionable ways. Think of it as a modern version of ancient and medieval attempts to seek happiness by putting one's soul in order.

That these might be live options for those seeking to answer life's deepest questions and to find a way of escaping unhappiness is something that Harris appears not even to have considered. That's his right; it's his book, after all.

But then he really should have chosen a different title. Far from showing his readers the surest path to waking up, Harris ends up telling them just enough to lull them to sleep.

Damon Linker is a senior correspondent at TheWeek.com. He is also a former contributing editor at The New Republic and the author of The Theocons and The Religious Test.