Resurrecting the book market of Baghdad

When a car bomb obliterated Iraq's millennium-old literary heart, a bookseller 7,000 miles away resolved that the voices of Al-Mutanabbi Street would not be forgotten

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

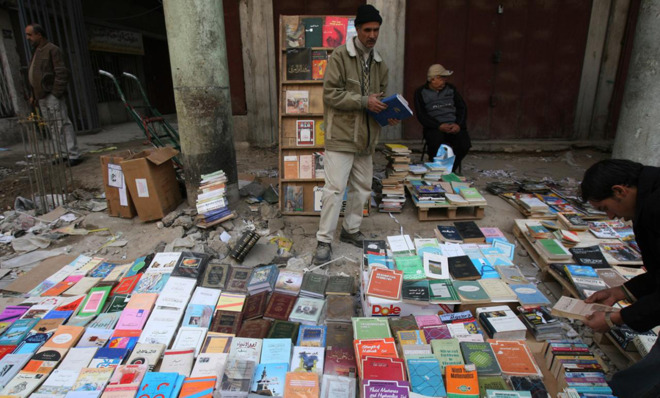

Before the bomb, Al-Mutanabbi Street in Baghdad appeared to be made of books: they littered the sidewalks, waved from tables and carts, sat on shelves inside bookstores, and peeped at passersby through the windows. The booksellers, like hawkers at the market, advertised the freshness and nourishment of their wares, tempting bookworms with what was in season, from a first edition to an eighteenth-century manuscript to the latest book in a foreign language. Dusty children dodged ivory-colored Ottoman pillars and piles of books as tall as themselves to pry wallets and phones from the pockets of eager book buyers, who realized their loss only after they had sought refuge in al-Shahbandar Coffee House for a drink and a smoke. Before the bomb, the nooks and crannies of Al-Mutanabbi Street were the classrooms and libraries where enlightenment sparked, master's theses began, doctoral research continued, and publications celebrated. Dictionaries and diaries, notebooks and novels, pencils and portraits canoodled late into the night, and no journalist, writer, student, or professor ever felt ill-equipped on Al-Mutanabbi Street. Signs for each bookstore and stationery shop were crammed one below the other, a clutter of titles tempting those below. Before the bomb, politics were challenged, poetry recalled and recited, dominoes won, hookah enjoyed, and radio alternated between the news and Oum Kalthoum's songs, which students, professors, clerics, and tourists alike stopped to absorb.

(More from Narratively: Kurt Thometz's little black bookshop)

On the morning of March 5, 2007, a car bomb exploded and Al-Mutanabbi Street. Bookstores turned into burned-out shells, infinite reams of paper endlessly aflame, the smell getting stuck in every crevice of Al-Mutanabbi Street, the sound of flicking pages smothered by coughs and cries. Thirty were killed and one hundred wounded; the street was destroyed, al-Shabandar Coffee House a mass of rubble and smashed water pipes. The New York Times reported that firefighters turned their hoses onto the smoking ruins, "only to have flames reignite because the paper had been transformed into kindling." It was as if the literary and cultural center of Baghdad, symbolic of the knowledge exchange that had taken place here since the eighth century, was mourning itself.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

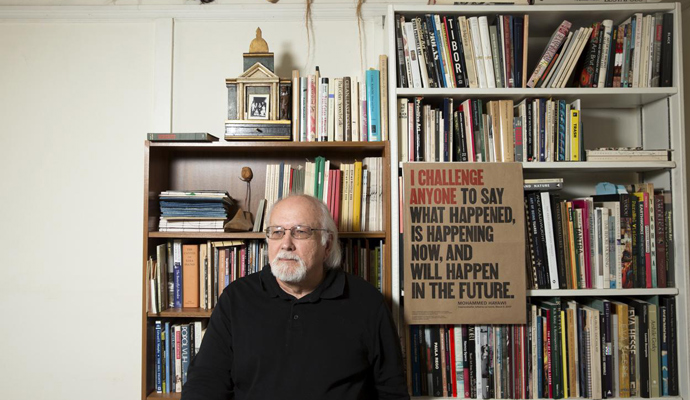

It is unclear whether or not the bomb was directed at the pages of learning, discovery, and curiosity that had brought book lovers from all over the world to Al-Mutanabbi Street, where the old Arab saying "Cairo writes, Beirut publishes, Baghdad reads" echoed off all the pillars. No one claimed responsibility. But when Beau Beausoleil read about the bombing of Al-Mutanabbi Street the day after it happened, sitting at his kitchen table on Lisbon Street in San Francisco, he could feel the ash on his fingers. "My bookstore would have been on that street," he says. "That forced distance between myself and the Iraqi people dropped away. I was no different from any Iraqi in that situation."

Beausoleil is an ex-army sergeant and cryptographic repairman in his seventies who has worked in bookstores for most of the last forty years, and run his own in San Francisco for the past ten. Literature has been part of his daily routine since he can remember, and his eleven published books of poetry are a testament to his dedication to the arts. He wears a long white beard and speaks carefully.

(More from Narratively: Print ain't dead in NYC)

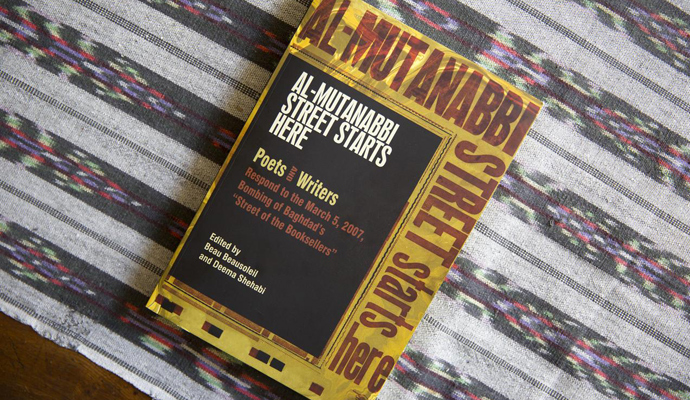

Beausoleil speaks in metaphor not just out of habit but because metaphor builds bridges in language — what he is trying to bridge in real life with Al-Mutanabbi Street Starts Here, the coalition he founded. "We are among the pages of every book that was shredded and burned and covered with flesh and blood that day," he proclaimed in the first flyer of protest he printed only a few weeks after the bombing. He also shared it over e-mail with poets, writers, and artists he knew, and they spread the word over the "arts grapevine."

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

What was until now an ongoing national crisis had become immediately personal to Beausoleil. In order to do something more than print posters, he turned to the people he thought would best express his pain and channel their own: letterpress printers. Reduced today to printing wedding invitations and literary minutiae, letterpress printers regularly produced provocative broadsides until as recently as the Vietnam War, which Beausoleil protested against on the streets of California, having spent time in Korea and on a ship in the Pacific working in cryptography and missile testing before leaving the army. "Those sheets could be put up on the side of a building, or the side of a tree, to bring people together, and I wanted that again," Beausoleil says. "I wanted something large and physical that people would encounter," that announced and aroused the public outrage they had in decades past. With their trademark bold lettering — think posters, playbills, "wanted" notices — broadsides were suited to be the "first responders" to the destruction of Baghdad's bookselling community.

If broadsides were people, they would be opinionated, confrontational. Dr. Simran Thadani of the University of Pennsylvania, who holds a doctorate in English with a specialty in book history, uses the word "extravagant." Giving the example of "The Ninety-Five Theses" that Martin Luther pinned to the door of a church in 1517, she points out that broadsides not only had to attract public attention and be legible but were only printed on one side. "Half their possible printing area was wasted," she says, forcing broadsides to be loud and eloquent in limited real estate. Thadani compares them to newspapers, which are as "large and physical" as a broadside and often called "broadsheet" print. There is a relationship. "The broadside might well be considered a kind of proto-newspaper," she says.

(More from Narratively: Dear dusty old bookstore)

So it is not surprising that Beausoleil, similarly steeped in literature, went straight to the broadside to disseminate headlines of solidarity to the public. "There is a tactile experience of reading," he says, "a physical manifestation of words and language and emotion." Thus galvanizing his world of writers, poets, booksellers, and artists, he led them into a liminal space that merged Lisbon Street and Al-Mutanabbi Street, where broadsides expressed and gathered community and where lines of poetry could turn into tangible art. After a successful inaugural exhibit of broadsides in San Francisco in September 2007, he began organizing broadside exhibits and readings in allied cities around the country. The first reading was at the San Francisco Public Library, where Sinan Antoon, an Iraqi poet and novelist with a doctorate from Harvard University and currently teaching at New York University, was the first to get up and read, and shared his poem "Wars."

when I was torn by war

I took a brush

immersed in death

and drew a window

on war's wall

I opened it

but

I saw another war

and a mother

weaving a shroud

for the dead man

still in her womb

Thadani understands Beausoleil's impulse — intuition, even, for the broadside. "Because of the nature of the crime — the obliteration of Baghdad's book district — the reaction to create book art and new printed artifact seems absolutely perfect, not only as a means of responding to the crisis but also to jump-start new cultural creation out of that moment of destruction," she says.

"Shared cultural spaces have always been under attack; there had to be a response from my own cultural community to a tragedy like this," Beausoleil says. But community does not equal commiseration. "It's not sympathy that we're looking for. It's a recognition of what is already there, that we share this space, this cultural space, all cultural spaces. An attack on one is an attack on us all."

Al-Mutanabbi Street was like so many streets all over the world where books are sold, bought, browsed, thumbed through, read. "Anywhere where someone sits down and begins to write towards the truth. Anywhere where someone picks up a book to read. That's where Al-Mutanabbi Street starts," Beausoleil says, explaining how the project got its name. Starting in San Francisco, he names the street where the Arab Cultural Center is located. Then the street where the Cambridge Arts Council is located. A street in Cambridge, Boston, San Francisco, Omaha, Detroit, New York — all sites of exhibits and memorial readings since the bombing. And in Damascus, Aleppo, Beijing, Tehran, the metaphorical extension of Al-Mutanabbi Street."All of those places hold artists and writers that want to write towards the truth. We honor all of those people — this project does — and feels that there's room on Al-Mutanabbi Street for all of us to stand together."

Which is how 130 broadsides — symbolic for the 130 dead and wounded on March 5, 2007 — were printed by 2010, by letterpress printers in Europe, the US, and the UK. Beausoleil and his British co-coordinator, Sarah Bodman, then launched an artist book project. These are books created by artists, "who take the texts that they're working with into a place that is so deep within themselves that their own life can't help but be integrated into their work. And they take that, and then bring it from that deep place, into a visual space, that we can all share," Beausoleil says. Artists collaborated with contemporary poets, or drew from a database of North African and Middle Eastern poetry that Beausoleil compiled, to create eye-catching, evocative pieces of art inspired by the physicality of a book: a toy truck with paper bursting out of the back; burned pages of poetry stitched together with fabric. Beausoleil requested artists to create three versions of each book, so that they could be exhibited as internationally as possible, accompany readings and supplement shows of the original 130 broadsides.

Read the rest of this story at Narratively.

Narratively is an online magazine devoted to original, in-depth and untold stories. Each week, Narratively explores a different theme and publishes just one story a day. It was one of Time's 50 Best Websites of 2013.