How to save American exceptionalism

We can start by recognizing what is truly unique about America's place in global affairs

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Can the notion of American exceptionalism be saved? President Obama's commencement address at West Point, billed as a major foreign policy address, was widely panned for being platitudinous and for overusing the convention of casting himself as the sensible moderate amid raving extremisms. But the president was right about one thing. If America is an exceptional nation, it's not because of war.

"American influence is always stronger when we lead by example," Obama said. "We cannot exempt ourselves from the rules that apply to everyone else."

He later emphasized the point: "[W]hat makes us exceptional is not our ability to flout international norms and the rule of law; it is our willingness to affirm them through our actions."

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

The first half of each of these quotes is absolutely correct. It is the second half that is a bit of revisionism, and not the best. For Obama, American exceptionalism should be about playing by the rules of international law, and being sufficiently chastened by historical example. For many foreign-policy thinkers, this reconception is the only way forward for a nation that has matured from its wild expansion and heady success. It's the only possibility for a superpower that has much to gain from a stable world order.

If you accept the truth of that, then of course it is tempting to write off the entire concept of "American exceptionalism" as a silly nationalist piety. The American republic has no divine guarantees. It will meet the same fate as Rome and the British Empire. It will die one day as do all worldly political institutions. At best, our job is simply to make good use of this republic's genius while we can.

Precisely because this is such a grim reconception, a kind of prudence for prudence's sake, it has never really made an impression on the hustings. It has none of the resonance of JFK's "Bear any burden," or the force of Reagan's "Tear down this wall!" There's something of an aristocratic weariness in it, too: "Twas always thus, and ever will be."

But an older definition of American exceptionalism is still useful, and certainly more acceptable to a democracy. Charles Francis Adams — a descendent of President John Adams who worked in the Lincoln administration and had a career as a medievalist up until the Progressive era — gave it a good voice at a speech to the Anti-Imperialist League in 1898.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Adams pointed to Washington's Farewell Address, which warned against "entangling alliances," and to the Monroe Doctrine, which warned Europe against interfering in the Western Hemisphere, as the two principles that allowed America to grow and prosper. The modern notion of American exceptionalism would be utterly foreign to Adams:

Having announced that our purpose was, in homely language, to mind our own business, we warned the outer world that we did not propose to permit by that outer world any interference in what did not concern it. America was our field — a field amply large for our development. It was therefore declared that, while we had never taken any part, nor did it comport with our policy to do so, in the wars of European politics, with the movements in this hemisphere we are, of necessity, more intimately connected.

Obama looks out on the world and sees nations playing according to their self-interest within international norms, and wishes that American idealism was used to shore up a world order that mostly benefits us. But Adams sees the world as a set of traps and irrational habits. In his view, Europe is a madhouse of empires, and its history is one of bloody familial intrigues — snares for a republic conceived in liberty.

Adams had all sorts of reasons for preferring the old republic, not all of them commendable. But he was not alone in lamenting America's own rush to empire. E.L. Godkin, seeing the massive investment in a world-class navy, complained bitterly that "when we get our navy and send it round the world in search of imputations on our honor, we shall have launched the United States on that old sea of sin and sorrow and ruffianism on which mankind has tossed since the dawn of history."

America was exceptional only in this sense: that it was a hemisphere away from Europe, and that it would eventually achieve peaceful relations with its two major neighbors. We had liberty, and after the horrors of the Civil War, we had peace. Why risk it, and the bodies of our young soldiers, trying to tame the lunacies across the world?

A sense of disgust and confusion with the world — not jealous admiration — is exactly what motivates a more sensible and restrained foreign policy. It's not that we should sober up, but that they are drunk. I've called it a "blame foreigners first" isolationism.

Isn't the Middle East just as confusing as the Europe of the 18th and 19th centuries? What did America accomplish in Egypt by sponsoring a brittle authoritarian, then consenting to his overthrow? What of our fly-by war in Libya? And what did Obama think he could do in Damascus?

Our foreign-policy mandarins still can't decide if Vladimir Putin is being bold, stupid, or both in Ukraine. Even the relatively prosperous European Union is suddenly challenged by hard-core nationalists, a phenomenon thought to have been expunged by the bureaucracy in Brussels and bombs in Kosovo.

Redefining America's exceptionalism as the solemn duty to be the most well-behaved, as Obama does, will only further isolate the American people from their policymakers. It will also end up blinding the foreign-policy elite to the dangers they cannot master.

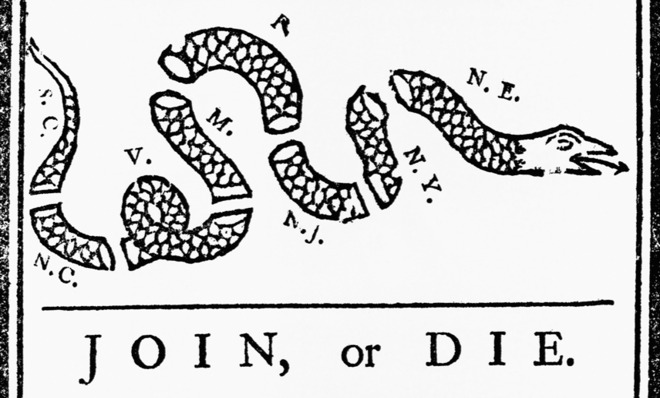

American exceptionalism is not a myth, though it may be the happiest of accidents. The silly notion that Americans must give up is that of a peaceful and predictable world order that we can maintain through exertions — and that bids us "Join or Die" when it really asks that we should do both.

Michael Brendan Dougherty is senior correspondent at TheWeek.com. He is the founder and editor of The Slurve, a newsletter about baseball. His work has appeared in The New York Times Magazine, ESPN Magazine, Slate and The American Conservative.

-

Political cartoons for February 21

Political cartoons for February 21Cartoons Saturday’s political cartoons include consequences, secrets, and more

-

Crisis in Cuba: a ‘golden opportunity’ for Washington?

Crisis in Cuba: a ‘golden opportunity’ for Washington?Talking Point The Trump administration is applying the pressure, and with Latin America swinging to the right, Havana is becoming more ‘politically isolated’

-

5 thoroughly redacted cartoons about Pam Bondi protecting predators

5 thoroughly redacted cartoons about Pam Bondi protecting predatorsCartoons Artists take on the real victim, types of protection, and more