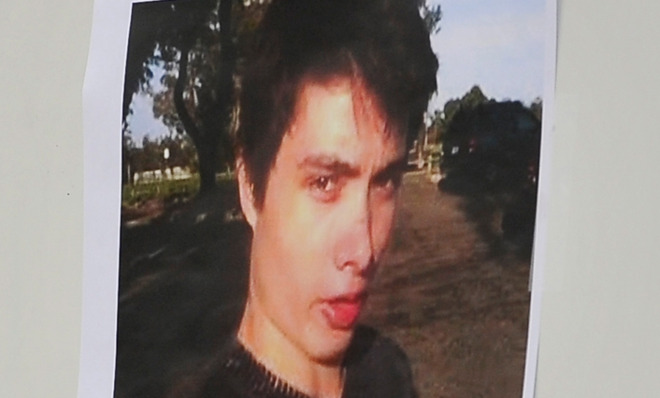

Elliot Rodger and The Secret

A 2007 self-help book that promised revolutionary powers did not change Elliot Rodger's trajectory

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Readers of Elliot Rodger's manifesto have found much that explains to their minds his descent into misogyny and madness. Several themes overwhelm repeatedly: his sense of entitlement, his sexual frustration and his obsession with the psychology of pretty women. Since he is a murderer, we owe him no sympathy for his crushing depression. But it might be wise to take a look at what he wrote about the way he thought as he tried to grip the sides, having so often fallen into deep holes. I noticed a few things that defy the stereotype of the lonesome loser.

The first was that Rodger had access to the best mental health care that money could buy, and a family that, even in the man's own accounting, was devoted to his care. They were not inattentive. They did not miss signs. They really tried. He had counselors, even people who were paid to spend time with him, to help him adjust.

His therapists were mostly good. Not just credentialed, none of them were psychoanalytic isolationists. They worried about his daily life and stressed the importance of place and experience in his case.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Rodger writes that he meditated. Meditation, done properly, is a therapeutic adjunct for depression and can help many people.

He was not isolated. He had friends, and people who loved him and told him so, not just with gifts but also with their time and with attempts to recognize his own significance. Rodger did not slip through any cracks, as the old familiar metaphor would have it. Of course, he grew to resent his friends, and when they struggled to muster the strength it takes to care for depressed people, he recognized this, used it against them, became self-pitying, and pushed them away.

Finally, and most significant to me, at least in terms of something that's a takeaway: he spent months in the cheery world of Rhonda Byrne's The Secret, the 2007 self-help volume that Oprah Winfrey embraced and then threw to the top of the best-seller lists. Here is what Eliot Rodgers writes:

My father gave me a book called The Secret after I had dinner at his house in February. He said it will help me develop a positive attitude. The book explained the fundamentals of a concept known as the Law of Attraction. I had never heard or read anything quite like this before, and I was intrigued. The theory stated that one's thoughts were connected to a universal force that can shape the future of reality. Being one who always loved fantasy and magic, and who always wished that such things were real, I was swept up in a temporary wave of enthusiasm over this book. The prospect that I could change my future just by visualizing in my mind the life I wanted filled me with a surge of hope that my life could turn out happy.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

This is an able summary of the book. Rodger goes on:

The idea was ridiculous, of course, but the world is such a ridiculous place already that I figured I might as well give it a try. In addition, I was so desperate for something to live for that I wanted to believe in the Law of Attraction, even if it was proven to me that it wasn’t real. Once I finished reading it, I drove all the way to Point Dume in Malibu and climbed out to the cliffs at the very edge. It was a windy day, and I could see the ocean roiling below me. As night fell, I looked out to the stars and proclaimed to the universe everything I wanted in life. I proclaimed how I wanted to be a millionaire, so I could live a luxurious life and finally be able to attract the beautiful girls I covet so much.

Lest you think that the book does not recommend that people do what Rodger did in Malibu, well yes. Yes it does. Lest you think the book couldn't possibly be targeted at people who find life at present too mysterious to bear, a life full of pleasure that only the some have access to, well, you're wrong again. Yes, of course it does. Slate's Emily Yoffe noticed how Byrne made it easy to both want and will into existence $1,000,000 and how she conjured up a world where randomness and misery are not norms for people who simply think differently. "Imperfect thoughts are the cause of all of humanity's ills, including disease, poverty and unhappiness."

For most of us, for 99 percent of us, The Secret is drivel. For some — actually, for millions and millions — it's mildly comforting pablum. What it's not is a philosophy for living, or for those recovering from, or struggle with, mental illness.

Since The Secret encourages fantasy and a belief in magic, I wonder if the credentialed and legitimate positive psychology movement, which does make meaningful contributions to the advance of happiness, should use the Rodger manifesto as a teaching example.

Marc Ambinder is TheWeek.com's editor-at-large. He is the author, with D.B. Grady, of The Command and Deep State: Inside the Government Secrecy Industry. Marc is also a contributing editor for The Atlantic and GQ. Formerly, he served as White House correspondent for National Journal, chief political consultant for CBS News, and politics editor at The Atlantic. Marc is a 2001 graduate of Harvard. He is married to Michael Park, a corporate strategy consultant, and lives in Los Angeles.