Matt Bell on readerly impulse, tastemakers, and the gatekeepers of publishing

An interview with the acclaimed author and scholar

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

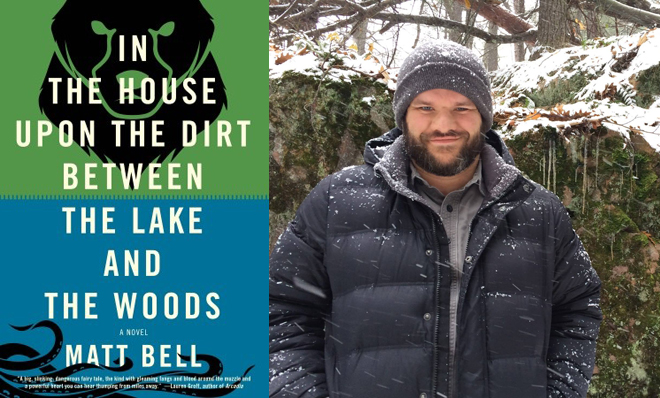

When I spoke recently with Matt Bell about his debut novel, In the House Upon the Dirt Between the Lake and the Woods, he joked that he has enjoyed watching writers attempt to condense the book's plot into a paragraph. I laughed when he said that, but didn't find it so funny when I sat down to do that very thing.

In the novel, magical songs spin the world into being, and peril arrives in the form of a mysterious, mystical bear that is both a ferocious threat and an ally linked by tragedy. Needless to say, it's an unconventional story told in a fabulist style.

The story tracks the marriage of an unnamed husband and wife, and the problems that result from repeated miscarriages and the prospect of no children. "And in this room: My wife pleading that a husband and a wife is still a family. That two is enough. And then, in another room down the hall, my voice replying, my voice saying, No." Bell's prose is subtle, patient, and engrossing, and it takes about a page to immerse the reader in this mythical world, and a chapter to really invest the reader in the uneasy marriage of the central characters.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

This is Bell's third book. His first was a collection of short stories, which was followed by a novella. He is the senior editor at Dzanc Books, and an English professor at Northern Michigan University. Below is a (slightly edited) transcript of our recent telephone conversation.

How would you describe the state of literature today?

It's a challenging publishing environment right now. The relationship between brick-and-mortar stores and e-books is changing everything, especially with independent presses getting more ink in the national conversation, and the innovative ways they're changing the model. Access to books has never been better. I grew up rural Michigan, where there were literally no bookstores. Well not literally — there was a Waldenbooks at the mall, and a store that sold used history books. Now, of course, anything I want to read I can get in a day or two, or 15 minutes later, even. In that respect, publishing is very healthy.

There's been a lot of talk about the [Master of Fine Arts degree in creative writing] being a corrupting influence on fiction, but I don't buy that. If I bought that I wouldn't be teaching it! We have this growing group of people who are being educated as readers and writers and artists, and that can only be good for us. And it's geographically decentralized. I lived in Michigan my whole life. In Saginaw there wasn't any access to the national organism of publishing. Because the internet is increasingly equalizing access, it's more and more common that an author can live anywhere and do good work and be recognized, which maybe wasn't true 50 years ago. So there are challenges in the industry, but overall there's more access than ever before, more variety than ever before, and that's only going to increase.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Are the traditional gatekeepers of publishing going to become more or less important going forward?

There are always going to be gatekeepers. There's no barrier to getting into the marketplace now. You can write something and have it on Kindle in five minutes. But the barriers to attention, and to critical attention, are still there. Some things will change. I think that an editor plucking you out of a pile in a big press is always going to help. And though there are a lot of people who shoot through the process without those gatekeepers, the gatekeepers appear in other places. Access to awards, grants, publicity — the gatekeepers will always be there. And we rely on that.

We need tastemakers that we trust to give us recommendations. That is not going to go away — it's maybe more prevalent and important than ever. Amazon reviews have democratized reviews, to an extent, but not for me. I joke that there are books that are too good for Goodreads. You go read classic books, and the Goodreads reviews are like one-star, right? "I read Moby-Dick in high school and I hated it and so it is terrible." So I think we'll always have a need for people who are tastemakers and culture-makers in that way.

So what is a great work of fiction for you?

So many things. I think my favorite book that I go back to over and over and over is Denis Johnson's Jesus' Son. That's my core text in some ways. It's an important work of literature for me as an adult. Cormac McCarthy is really important to me. I think while learning to write, I read people like Christine Schutt, Amy Hempel, Raymond Carver, Hemingway. I read widely and everything becomes an influence for me. But core works that don't go away, for me, are myths and fairy tales, which have been an important part of my entire life, and only increase in importance. Those are the things I go back to maybe more than anything in contemporary literature.

How did you decide on the fabulist style for your first full novel?

I wrote a couple of novels before this that I never even sent out. I was aware that they weren't good enough, that they were much more derivative — you could clearly see their roots in other people's books. As far as the style in this book, I think that I can't really start until I have a voice, and so it came from the voice of the narrator first. When he started speaking he went to intriguing places. I think there's obviously some King James Bible there, obviously some Cormac McCarthy there, some fairy tales there. It's definitely incorporating things I love already.

So I'm aware it's sort of a weird voice, but it's the voice I was interested in writing. I didn't know what the book was going to be about when I stated writing initially. I didn't know that I ever really understood what the book was about thematically until I reread the first draft. The voice was the initial interest, and it generated the other stuff. I wouldn't have told this story if I were writing in a more typical American narrative voice.

The lifetime of literature you drew from — how did that influence your journey from reader to writer?

I wrote a little bit when I was young. I wrote a novel in grade school that was every scene from everything I'd ever read. That kind of writing is — it didn't stick. I don't remember writing in high school, and in college I wrote really bad poetry that was really more related to liking music than it was about liking poetry. I was writing poems that were like bad song lyrics. I didn't start seriously writing fiction until I was 20 or 21. I started reading Vonnegut, and one summer I think I read everything he'd written. And then Chuck Palahniuk, Denis Johnson, Amy Hempel. Raymond Carver — something about reading those five writers really sparked something. Almost immediately I was like, "That's what I'm going to do with my life." Like I was waiting to discover it. I immediately became a serious writer, and I went back to college and started up an English degree.

I really began as a reader. And it was — there were these people I was reading and I didn't know where to go next. I didn't know enough about books to know that if I like these five people, who else should I be reading? So I started make my own version of their stories in some ways just to have more of them. The writing initially was a readerly impulse and in some way still is.

How has success affected the way you write now, and how does it affect the way you teach?

It's interesting when some grad students aren't aware that you are also a writer — like high school teachers who aren't necessarily active in their field. I teach books that I love or admire, or ones that get reactions that I think are a helpful experience. I try to teach students not to write like me, but rather, to write like themselves. It's hard to think of yourself as an influencing force. That would be a weird way to see myself, although it's certainly humbling and nice that people feel that about the work.

I think that writers — as far as my writing, the only thing interesting to me is that you don't repeat yourself. You try not to, anyway, as much as you can avoid it. The next book should come at things in a different direction. The writers I admire most, the differences between their books are as interesting as the similarities. Right now I'm working on a novel that comes out from Soho Press in 2015. It's a literary thriller that takes place among the illegal metal scavenging in Detroit. It's a contemporary novel set in a real place this time — no magical bears. It's a completely different kind of voice and a different approach.

I'm teaching a novel-writing class right now. My grad students all start new novels on the first day and they have word count goals, and it's so amazing to get to talk about novel writing to ten smart people every week — what a boost for myself. I'll bounce ideas off of them, and think, "Oh yeah, I need to do that in my novel, too." Teaching is very helpful. I think we have fun in class. God knows I'm getting a lot out of it.

David W. Brown is coauthor of Deep State (John Wiley & Sons, 2013) and The Command (Wiley, 2012). He is a regular contributor to TheWeek.com, Vox, The Atlantic, and mental_floss. He can be found online here.

-

The ‘ravenous’ demand for Cornish minerals

The ‘ravenous’ demand for Cornish mineralsUnder the Radar Growing need for critical minerals to power tech has intensified ‘appetite’ for lithium, which could be a ‘huge boon’ for local economy

-

Why are election experts taking Trump’s midterm threats seriously?

Why are election experts taking Trump’s midterm threats seriously?IN THE SPOTLIGHT As the president muses about polling place deployments and a centralized electoral system aimed at one-party control, lawmakers are taking this administration at its word

-

‘Restaurateurs have become millionaires’

‘Restaurateurs have become millionaires’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day