The brutal honesty of a 19th century bloodsport baron

"Rats are vermin," he once said. "And dogs will fight, for 'tis their nature to."

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

They took Kit Burns to Cavalry Cemetery three days before Christmas, in a hearse drawn by six white horses. A crowd had gathered for his wake at his daughters' house in Brooklyn, and after a viewing, the mourners moved outside, into the cold, to escort the body on foot some 10 miles to Queens. The procession was sufficiently numerous — and festive — to form a parade. In a rosewood coffin inlaid with a delicate silver cross, Burns lay dressed in garb more sedate than the bright shirts, golden chains and pantaloons striped with gang colors he had favored in life. His ruddy complexion ornamented a robust prizefighter's frame, while narrow eyes and a red corsair's beard lent him some semblance to Van Gogh's Postman.

Beyond his clothing, death had not much changed his appearance. It was said that those assembled gazed at Burns as if he were a spiritual medium, a religious leader, prophet, or saint. In his 39 years, he had survived four bullet wounds, and a knife to the neck taken during a brawl at Dan Kerrigan's Cherry Street bar. In the winter of 1869, a year before his death, reporters as distant as Kansas and Montana advised readers that complications from a rat bite had placed him in precarious, near-terminal condition. Such were occupational hazards for Burns, a saloonkeeper by trade, who was also perhaps the country's greatest impresario, before or since, of bloodsport. An assiduous organizer of combat amongst rodents, dogs, men — and, occasionally, bears — he had in his lifetime overseen the slaughter of thousands of rats.

(More from Narratively: Her golden gloves)

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

The death notices furnished decidedly mixed reviews: Commercial Advertiser named Burns "a genius in disguise; a democrat by birth," and "a fellow of the Metropolitan Society of the Slums," while the Jackson Citizen Patriot predicted that, leaving the temporal sphere, Burns would report directly to "the bottomless [pit]." Citizens and Round Table wrote of his departure, simply: "We are glad of it." Henry Bergh, the well-heeled scion of a New York industrial family — and the founder of the American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (ASPCA) — would later boast: "I drove him out of New York and into his grave."

For Bergh, there could have been scarcely any evil greater than Burns, who'd presided over a dog and rat-fighting pit that was, by the late 1860s, one of few in Manhattan he had failed to shutter. But Burns was incredulous. He considered his occupation legal as any, and could not fathom objections to it. Burns did not fault Bergh for his efforts; he seemed rather to respect the earnestness with which he approached his mission. He could not, however, access the reformer's logic. For Burns, violence and cruelty were only distantly related — by perversions of which he considered himself innocent. Violence itself seemed to him no sin. "Rats are vermin," he once said. "And dogs will fight, for 'tis their nature to."

Born Christopher Keyburn in Donegal, Ireland in 1830, Kit Burns immigrated to New York around 1845, one of hundreds of thousands who fled the potato famine for American shores. Burns' parents did not accompany him on the voyage, though his older brother George — who later became a police officer — might have. In 1860, when Burns applied for naturalization, George stood witness. Their father did not arrive until two years later.

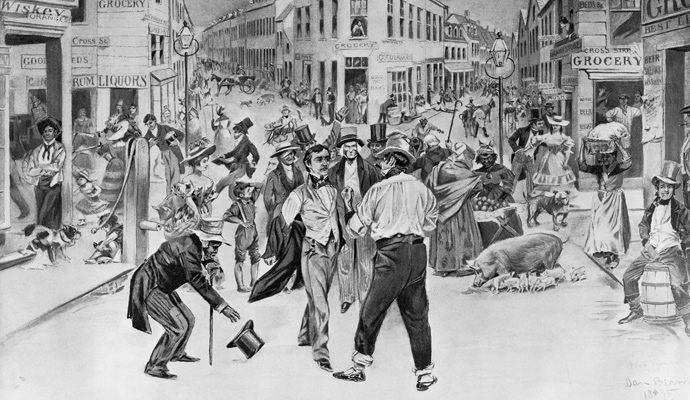

The Five Points neighborhood of Manhattan, where Burns first settled, was a squalid district named for the intersection between Orange, Cross and Anthony Streets in modern Chinatown. Between 1830 and 1855, Five Points's population nearly doubled, to some 25,500, of which Irish immigrants accounted for a great majority. Per capita income in the area hovered far below the citywide average, and the streets were thicketed with cramped tenements dominated on some blocks by cut-rate brothels, the basements of which hosted oft-flooded inebriate flophouses. Beneath these buildings, filled in with earth dug from Bunker Hill, lay the Collect Pond: a lake gone rancid with tannery and slaughterhouse runoff. Outhouses stood close beside wells and alcoholism ran rampant. Practically nowhere was crime more prevalent. Northern abolitionists faced accusations of hypocrisy: Life in Five Points, slavers charged, was far crueler than even the most brutal kind of plantation existence. The Scandinavian activist Fredrika Bremer, among others, saw things in vaguely evolutionary terms: "Lower than to the Five Points," she wrote, "it is not possible for human nature to sink."

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

(More from Narratively: Zen and the art of whip cracking)

Still, as the historian Tyler Anbinder notes in his book Five Points, the neighborhood's turmoil bred an unprecedented and characteristically American social shift. After 1834, the Five Points' political nobility "comprised saloonkeepers, grocers, policemen and firemen rather than manufacturers and wealthy merchants… the old elite that had governed the city for centuries." "The liquor-dealer is [the tenement dwellers'] guide, philosopher and creditor," a reporter for The Nation wrote. "He… is the person through whom the news and meaning of what passes in the upper regions of city politics reaches them." For a price, saloonkeepers could thus deliver substantial voting blocs to angling politicians, and many Five Pointers viewed bar ownership as a zenith of success.

If conditions in Five Points could bring on despair, they also fostered eager striving: "… most survived and eventually thrived," Anbinder writes of Five Points's immigrants, "establishing more prosperous lives for themselves and their families than would have been possible" in their native countries. For many, the underworld presented the most expedient trailhead to prosperity, and practically none found that ingress more inviting than Kit Burns.

In the late 1840s, Burns — like innumerable young men who've since grown up without the benefit of parental guidance in rough American neighborhoods — became involved in gang life. The Dead Rabbits were the largest of the Five Points gangs, to which thousands collectively belonged, and Burns rose quickly through their ranks. (In the parlance of the time, a "rabbit" — inexplicably — was a big, tough fellow. A "dead rabbit" then, was a fellow extremely big and tough.) The Dead Rabbits skirmished locally with smaller gangs, and nurtured longstanding vendettas with the Bowery Boys and Atlantic Guards, which roved nearby. They fought with fists and iron bars, brickbats, pistols, paving stones, pitchforks, and knives. They wore trousers emblazoned with red stripes and, as was the style, often battled in their undershirts. They drank to near-comical excess. (The journalist Robert Sullivan writes in his book Rats that, as an adult, Burns maintained a strict regimen of 20 glasses of liquor a day.)

(More from Narratively: The contender)

As a Dead Rabbit lieutenant, Burns often functioned more like a political operative than a modern gangster. Anbinder writes: "Election day in [Five Points] rarely ended without blackened eyes and bloodied lips," as gangs representing rival political factions staged polling place riots — destroying and stuffing ballot boxes, and intimidating would-be voters to tip the scales in their favor. (Two months before Burns's death, the Columbia Register identified him euphemistically as a prominent "protector of the ballot boxes.") To elect the venal and unprincipled Democratic Mayor Fernando Wood, in 1855, the Dead Rabbits fanned out in city cemeteries — compiling names to add to Wood's rolls — and deposited several chests of unfavorable ballots in the East River. Like virtually all politically active Five Pointers, the Dead Rabbits supported the rising Democratic Tammany Hall establishment, whose anti-abolitionist, pro-immigrant stance and antipathy toward restrictive liquor laws lined up neatly with local sensibilities. (The Bowery Boys and Atlantic Guards were leading enforcers for the opposition "Know-Nothing" party, which maintained a nativist platform.)

Though the riots Burns would captain through the 1850s and 1860s served to perpetrate corruption and fraud, they — like the saloonkeepers who had become neighborhood beacons — also exercised a democratizing influence, affording immigrants access to power structures formerly unavailable to them. Burns never showed interest in public office. But in 1867, when the New York Herald — a paper with nativist sympathies — listed him as a likely political candidate, it was with real and palpable concern. It was also a testament to the trust his community placed in him, and to how far he'd come since arriving two decades earlier, practically a child and all but alone in America.

Read more of this story at Narratively.

Narratively is an online magazine devoted to original, in-depth and untold stories. Each week, Narratively explores a different theme and publishes just one story a day. It was one of TIME's 50 Best Websites of 2013.

-

Hyatt chair joins growing list of Epstein files losers

Hyatt chair joins growing list of Epstein files losersSpeed Read Thomas Pritzker stepped down as executive chair of the Hyatt Hotels Corporation over his ties with Jeffrey Epstein and Ghislaine Maxwell

-

Political cartoons for February 17

Political cartoons for February 17Cartoons Tuesday’s political cartoons include a refreshing spritz of Pam, winter events, and more

-

Alexei Navalny and Russia’s history of poisonings

Alexei Navalny and Russia’s history of poisoningsThe Explainer ‘Precise’ and ‘deniable’, the Kremlin’s use of poison to silence critics has become a ’geopolitical signature flourish’