Why I miss the gritty greatness of the 1970s

It was a decade of disillusionment that produced some of the greatest moments in our cultural history

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

It might just be misplaced nostalgia for my youth (I was born in 1969), but it seems that every year I become more convinced that there was something special about American pop culture in the 1970s — something deep, gritty, dark, and tragic that flickered into being early in the decade and then winked out of existence just as suddenly a few short years later.

I miss it. And you should, too — whether or not you lived through the decade yourself.

For those of you too young to remember it, allow me to paint a picture of the indelible strangeness of the times. Rocked by years of campus protests, urban riots, war, assassinations, and countercultural upheaval, America seemed uncharacteristically lost and unsure of itself. The result, on a cultural level, might be described as un-American — not in the sense that the popular art of the time scorned American ideals, but in the sense that its predominant mood was disillusionment. And disillusionment runs counter to what is normally our prevailing national disposition of optimism, vitality, and self-confidence.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

The downcast vibe was especially jarring — though also strangely apt and even predictable — coming as it did so soon after the optimism that coursed through John F. Kennedy's inaugural address, animated Lyndon Johnson's domestic and foreign policies, and initially fueled the civil rights, free speech, and anti-war movements. In the early- to mid-1960s, America came close to overdosing on what is always its spiritual narcotic of choice: Hope for the imminent reformation and redemption of a fallen world.

The 1970s were the hangover. And it was a doozy.

Garry Wills saw it coming in Nixon Agonistes (1970), which predicted a looming crack-up of the hippie culture as its members confronted the reality of evil for the first time, and were finally forced to grow up and leave their drug-addled naivete behind them. The theme of disillusionment echoed through some of the decade's best fiction and nonfiction writing, from Saul Bellow's Mr. Sammler's Planet (1970) and Alfred Kazin's New York Jew (1978) to Christopher Lasch's Haven in a Heartless World (1977) and Culture of Narcissism (1979).

But it also left a mark on some of the greatest film and music of the era. The French Connection (1971) and Dog Day Afternoon (1975), Mean Streets (1973) and Taxi Driver (1976), The Godfather (1972) and Godfather Part II (1974), Badlands (1973) and Days of Heaven (1978), The Deer Hunter (1978) and Apocalypse Now (1979) — the decade was rich in cinematic explorations of moral ambiguity, existential confusion, and wrenching disenchantment.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

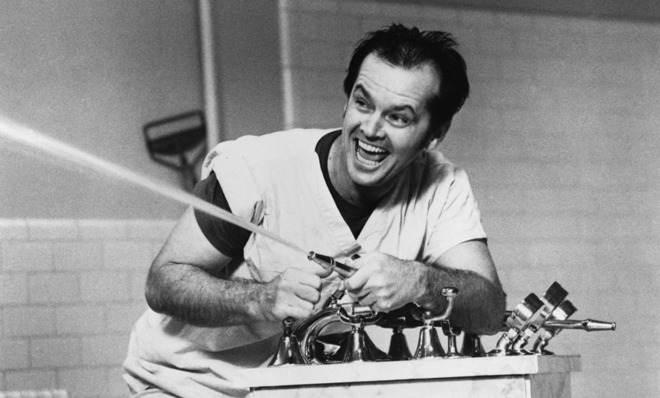

No less great is the remarkable series of dramas Jack Nicholson made between 1969 and 1974. Easy Rider (1969) and Chinatown (1974) are well known, but Carnal Knowledge (1971) is less so. That's a pity, since it may well be the greatest film ever made about the sexual revolution. Directed by Mike Nichols, it follows the romantic and sexual lives of two men (Nicholson's Jonathan and Art Garfunkel's Sandy) from their college days in the 1940s through to the early 1970s. In the film's early scenes, both men find it impossible to relate to women in any way other than as sexual objects, though the buttoned-down mores of the time require them to conceal it from their would-be conquests. By the end of the film, Sandy has made some progress in learning how to relate to women as equals, but Jonathan has devolved into a loathsome misogynist who can only perform sexually with prostitutes he pays to tell him lies about his masculine potency. It is a brutal and psychologically scalding film.

Five Easy Pieces (1970) may be even better. Funny, quirky, and emotionally devastating, the film tells the story of a man (Nicholson's Robert Eroica Dupea) who spends his life running away from his past and toward nothing but oblivion. In his restless refusal to sit still, he has the makings of a classic American hero, driven ever onward toward adventure and achievement. But in director Bob Rafelson's hands, he becomes the perfect anti-hero for the 1970s. Consumed by self-loathing and denying his own real talents as a pianist, Robert lives his life in flight from anyone who tries to love him, settling for odd jobs and then bolting for the door the moment the prospect of permanence begins to threaten him. Americans like to tell themselves it's always possible to "get a new life." Robert is a man addicted to the freedom that follows from self-erasure.

Similar themes resonate through the pop music of the era, especially in the plaintive songs of the singer-songwriters who rose to prominence early in the decade. Many of them were inspired by the folk tunes of Simon and Garfunkel, and it is Paul Simon himself who managed to write what should be considered the signature song of the 1970s: "American Tune" (1973).

Sung to a lovely melody adapted from a 16th-century composition by Hans Leo Hassler, Simon's melancholy lyrics perfectly capture the sense of drift and disorientation of those years.

I don't know a soul who's not been batteredI don't have a friend who feels at easeI don't know a dream that's not been shatteredOr driven to its kneesOh, but it's alright, it's alrightFor we lived so well so longStill, when I think of theRoad we're traveling onI wonder what's gone wrongI can't help it, I wonder what's gone wrong

As the song continues, Simon's worries and regrets meld into a dream of his own death and an afterlife in which his soul spies "the Statue of Liberty / Sailing away to sea." Other iconic nautical images from American history — the Mayflower sailing to Massachusetts, Apollo 11 sailing to the moon — float past him as well. By the end of the song, he's achieved a measure of disillusioned wisdom:

Oh, it's alright, it's alright, it's alrightYou can't be forever blessedStill, tomorrow's going to be another working dayAnd I'm just trying to get some restThat all I'm trying — to get some rest

No more great, world-historical goals. Just relaxation and recovery. And then a new day of humble toil ahead.

No singer-songwriter explored these diminished expectations with more emotional depth — or did more to trace their connections to the faded idealism of the 1960s — than Jackson Browne. In "For Everyman" (1973), Browne sings about how his own high hopes for collective change have given way to a realization that a better world must be forged by individuals, one well-intentioned person at a time. ("All my fine dreams / And well thought out schemes to gain the motherland / Have all eventually come down to waiting for Everyman.")

But what if disillusionment leads people to give up the effort for social improvement altogether in favor of building private visions of happiness? That was Browne's subject in his 1976 epic "The Pretender" (1976), which begins with him saying he wants "to know what became of the changes / We waited for love to bring," and wondering if they were "only the fitful dreams / Of some greater awakening." By the end of the song, he's resolved to become a "happy idiot," settled into a life of domestic bliss, with a job, neighbors, a romantic companion, and no ambitions beyond getting up the next morning "to do it again / Amen."

It has its allure. But doubts linger, encapsulated in the haunting plea with which Browne ends the song:

Say a prayer for the pretenderWho started out so young and strongOnly to surrender

One problem with a life devoted to the pursuit of domestic happiness is that you'll end up feeling like a fake and a coward who gave up the fight for a better world. Another is that you'll feel lost, disoriented, and depleted in the wider world — or as Browne put it in his breakthrough hit from 1978: "Running on empty / Running on — running blind / Running on — running into the sun / But I'm running behind... And I don't even know what I'm hoping to find." It's hard to imagine a more fitting expression of the aimless confusion of the Carter years.

But more than confusion and disorientation, a single-minded focus on private life can also breed political apathy and cynicism toward anyone with higher, more public aims. This was the flip side of the post-60s disillusionment that permeated the 70s — and it reached a kind of apotheosis in Billy Joel's "Angry Young Man" (1976), a spiteful polemic against would-be do-gooders everywhere:

I believe I've passed the age of consciousness and righteous rage I found that just surviving was a noble fight I once believed in causes too I had my pointless point of view And life went on no matter who was wrong or right

There's always a place for the angry young man With his fist in the air and his head in the sand And he's never been able to learn from mistakes So he can't understand why his heart always breaks And his honor is pure and his courage is well And he's fair and he's true and he's boring as hell And he'll go to the grave as an angry old man

The mockery of "consciousness and righteous rage," the romanticization of "just surviving," the pointlessness of having political opinions or caring who's wrong or right, and the head-buried-in-the-sand obliviousness of the committed citizen who also happens to be "boring as hell" — here we're just steps away from Ronald Reagan's sanctification of the private sphere and denigration of anyone tempted to put their faith in a public purpose.

There's a reason the 1980s emerged from the '70s.

But that doesn't mean there wasn't something serious and worth preserving in the melancholy art of disillusionment that was the distinctive contribution of the '70s to our cultural history.

Damon Linker is a senior correspondent at TheWeek.com. He is also a former contributing editor at The New Republic and the author of The Theocons and The Religious Test.