It's time to build a real Jurassic Park

Yes, I saw how the movie ended, but hear me out

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

When schoolchildren in the future learn about the woolly mammoth, they might not have to settle for a stuffed replica at a natural history museum. Scientists announced recently that they had collected enough genetic material to bring it back from extinction:

Scientists now say they've got enough blood and bone to bring an Ice Age icon kicking and stomping into the modern age. All thanks to a remarkably well-preserved mammoth found in Siberia last summer. "The data we are about to receive will give us a high chance to clone the mammoth," Radik Khayrullin, of the Russian Association of Medical Anthropologists, told The Siberian Times. [The Huffington Post]

And it's not just mammoths. Revive and Restore, a nonprofit organization advocating "de-extinction," has identified 24 candidate species that could potentially be brought back. In other words, a menagerie of extinct species, like the one from Jurassic Park, is in reach.

To be a candidate for resurrection, one needs adequate samples of DNA, and there must be a living species that is closely related enough to act as a potential surrogate parent. This rules out dinosaurs for the time being (in case you were wondering), but available candidates include passenger pigeons, dodo birds, Irish Elk (a giant deer from the ice age that had antlers 12 feet across) and even the saber-toothed tiger. (Perhaps Pliocene Park, not Jurassic Park, would thus be the more accurate title for a preserve of extinct species, even if it's not as evocative.)

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

But even where the necessary genetic material is available, there are still technical issues. Cloning a mammoth would be a more complex procedure than cloning Dolly the sheep. Scientists still need to fully map the genome of the woolly mammoth, a process that is currently around 70 percent complete, before they can determine whether de-extinction is feasible. The chances are good, however, as the revival of the once extinct gastric-brooding frog demonstrates.

But even if it's feasible to bring back extinct species like the mammoth — or even dinosaurs — in the future, would it be a good idea?

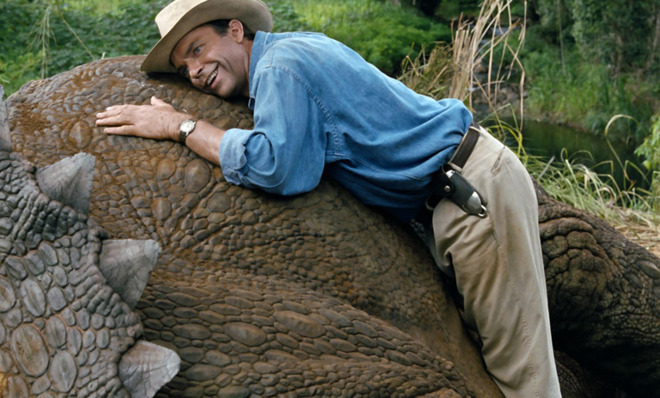

When the matter has been considered fictionally, the answer is almost invariably no. In Jurassic Park, for example, Jeff Goldblum's character Dr. Ian Malcolm condemns the notion an example of scientific hubris:

I'll tell you the problem with the scientific power that you're using here, it didn't require any discipline to attain it. You read what others had done and you took the next step. You didn't earn the knowledge for yourselves, so you don't take any responsibility for it. You stood on the shoulders of geniuses to accomplish something as fast as you could, and before you even knew what you had, you patented it, and packaged it, and slapped it on a plastic lunchbox… This isn't some species that was obliterated by deforestation, or the building of a dam. Dinosaurs had their shot, and nature selected them for extinction.

In the film, Goldblum's warnings are almost immediately vindicated when the resurrected dinosaurs escape their cages and wreak havoc. But while it may make for compelling filmmaking, the reasons presented are complete gobbledygook.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Far from being contrary to science, standing on the "shoulders of geniuses" is precisely how science works. In fact, the phrase itself is a garbled quote from Issac Newton. Nature does not in fact select species for extinction (the most widespread theory for why the dinosaurs died out involves Earth being hit by an asteroid, not as the result of some kind of cosmic death panel). While you wouldn't want to run into a velociraptor in the wild, modern zoos deal with a variety of dangerous and potentially deadly animals on a daily basis, and certain candidate species (such as the dodo bird) aren't particularly dangerous. Restoring old species would not only provide enjoyable field trips for kids, but could potentially add greatly to the store of human knowledge, helping us understand more about the development of life and why certain species do or don't survive.

More serious concerns are raised by the idea not simply of keeping resurrected creatures in zoos, but of reintroducing them into the wild. Introducing new species into an existing habitat can have unintended consequences, which deserve careful scrutiny.

But at a larger level, why are people so squeamish about resurrecting extinct species when we take such extensive action to protect endangered ones? If we are concerned about protecting the last red wolves, for instance, why shouldn't we bring back the Tasmanian tiger? If resurrecting select species is within reach, the gains in human knowledge and ecosystem diversity would be well worth the risks.

Josiah Neeley is a Policy Analyst for the Armstrong Center for Energy and the Environment at the Texas Public Policy Foundation.