Here's how to really detect lies

Stop looking for anxiety and start looking for "cognitive load"

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Lying well is hard — but not in the way you might think.

We usually look for nervousness as one of the signs of lying. Like the person is worried about getting caught. But that's actually a weak predictor.

Some people are so confident they don't fear getting caught. Others are great at hiding it.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Some get nervous when questioned so you get false positives. And others are lying to themselves — so they show no signs of deliberate deception.

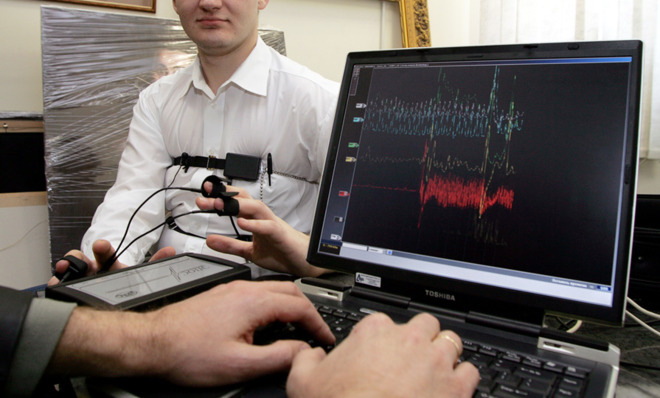

So lying isn't necessarily hard in terms of stress. But it is hard in terms of "cognitive load." What's that mean?

Lying is hard because it makes you think. You need to think up the lies. That's extra work.

Looking for nervousness can be a wild goose chase. Looking for signs of thinking hard can be a great strategy.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Lying can be cognitively demanding. You must suppress the truth and construct a falsehood that is plausible on its face and does not contradict anything known by the listener, nor likely to be known. You must tell it in a convincing way and you must remember the story. This usually takes time and concentration, both of which may give off secondary cues and reduce performance on simultaneous tasks. [The Folly of Fools: The Logic of Deceit and Self-Deception in Human Life]

This also means that many of the signs of lying we often look for aren't accurate. And things we're not looking for can be good indicators.

When nervous we blink our eyes more often, but we blink less under increasing cognitive load (for example when solving arithmetic problems). Recent studies of deception suggest that we blink less when deceiving — that is, cognitive load rules. Nervousness makes us fidget more, but cognitive load has the opposite effect. Again, contra-usual expectation, people often fidget less in deceptive situations. And consistent with cognitive load effects, men use fewer hand gestures while deceiving and both sexes often employ longer pauses when speaking deceptively. [The Folly of Fools: The Logic of Deceit and Self-Deception in Human Life]

So don't look for signs of stress, look for indicators that the person is thinking hard.

As Richard Wiseman's writes:

They tend not to move their arms and legs so much, cut down on gesturing, repeat the same phrases, give shorter and less detailed answers, take longer before they start to answer, and pause and hesitate more. In addition, there is also evidence that they distance themselves from the lie, causing their language to become more impersonal. As a result, liars often reduce the number of times that they say words such as "I," "me," and "mine," and use "him" and "her" rather than people's names. Finally, is increased evasiveness, as liars tend to avoid answering the question completely, perhaps by switching topics or by asking a question of their own.

To detect deception, forget about looking for signs of tension, nervousness, and anxiety. Instead, a liar is likely to look as though they are thinking hard for no good reason, conversing in a strangely impersonal tone, and incorporating an evasiveness that would make even a politician or a used-car salesman blush. [59 Seconds: Change Your Life in Under a Minute]

Those are helpful tips. But how do we take it to the next level?

What do experts at detecting lies do?

Increase load

They don't passively rely on common signs of lying. They actively seek to increase the suspected liar's cognitive load. And they deliberately make the person think harder to magnify the signals to a point where they are obvious.

That's what police detectives do:

- Have people tell their story backwards, starting at the end and systematically working their way back. Instruct them to be as complete and detailed as they can. This technique, part of a "cognitive interview" Geiselman co-developed with Ronald Fisher, a former UCLA psychologist now at Florida International University, "increases the cognitive load to push them over the edge." A deceptive person, even a "professional liar," is "under a heavy cognitive load" as he tries to stick to his story while monitoring your reaction.

- Ask open-ended questions to get them to provide as many details and as much complete information as possible ("Can you tell me more about…?" "Tell me exactly…"). First ask general questions, and only then get more specific.

- Don't interrupt, let them talk and use silent pauses to encourage them to talk.

Who you need to be wary of

It's not the dumb people. Cognitive load, remember?

Who can best handle thinking hard? Who comes up with great stories on the fly?

It's true: Smarter and more creative people are better liars.

From my interview with Duke professor Dan Ariely, author of The (Honest) Truth About Dishonesty: How We Lie to Everyone — Especially Ourselves:

So ask yourself who can tell better stories? It turns out more creative people can tell better stories, so that's actually what we find. We find it when we measure students that are more creative, they cheat more. We find that when we use priming to increase creativity, we also increase dishonesty.

It brings a smirk to my face whenever people wish for children that are smart and creative…

Yes, research shows you can tell how smart your child is by how early they start lying:

The complex brain processes involved in formulating a lie are an indicator of a child's early intelligence, they add. A Canadian study of 1,200 children aged two to 17 suggests those who are able to lie have reached an important developmental stage.

(And no, dear parents, despite what you may tell yourself you're not very good at discerning when your kid is lying.)

All this deception, and it's even more common among the intelligent and creative. What to do?

Maybe that's why when you survey people about the most important character trait you get an unsurprising answer — trustworthiness:

Participants in three studies considered various characteristics for ideal members of interdependent groups (e.g., work teams, athletic teams) and relationships (e.g., family members, employees). Across different measures of trait importance and different groups and relationships, trustworthiness was considered extremely important for all interdependent others…

Join 45K+ readers. Get a free weekly update via email here.

More from Barking up the Wrong Tree…

-

Gisèle Pelicot’s ‘extraordinarily courageous’ memoir is a ‘compelling’ read

Gisèle Pelicot’s ‘extraordinarily courageous’ memoir is a ‘compelling’ readIn the Spotlight A Hymn to Life is a ‘riveting’ account of Pelicot’s ordeal and a ‘rousing feminist manifesto’

-

The EU’s war on fast fashion

The EU’s war on fast fashionIn the Spotlight Bloc launches investigation into Shein over sale of weapons and ‘childlike’ sex dolls, alongside efforts to tax e-commerce giants and combat textile waste

-

How to Get to Heaven from Belfast: a ‘highly entertaining ride’

How to Get to Heaven from Belfast: a ‘highly entertaining ride’The Week Recommends Mystery-comedy from the creator of Derry Girls should be ‘your new binge-watch’