Here are all the big mistakes Malaysia made with Flight 370

The only things we know for sure are that a giant Boeing 777 has vanished, and Malaysian officials appear incompetent

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Nobody is giving Malaysia high marks for its handling of the disappearance of Malaysia Airlines Flight 370, which mysteriously vanished early March 8. In every high-profile mess — and losing a giant Boeing 777 with 239 people on board ranks very high — there are always people second-guessing and spitballing official decisions. But in this case, it appears Malaysia did drop the ball on a number of fronts.

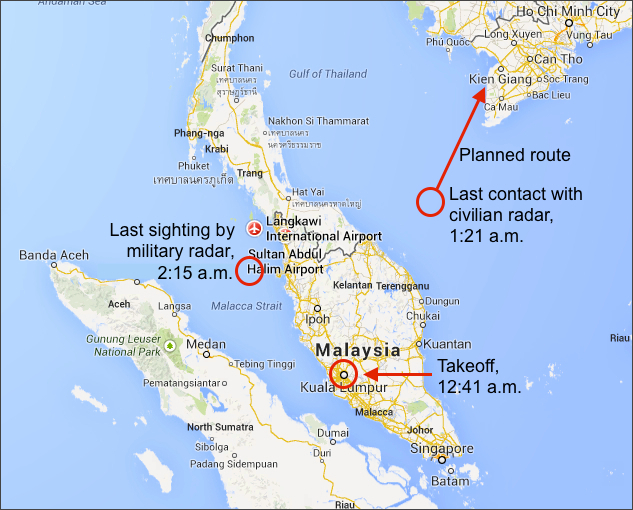

The timeline, according to the most recent information, goes something like this:

- Flight 370 took off from Kuala Lampur's airport at 12:41 a.m., heading northeast toward Beijing.

- About half an hour into the flight, the airplane's radio and tracking systems started shutting down. The last transmission from the Aircraft Communications Addressing and Reporting System (ACARS) was at 1:07 a.m., the final radio message ("all right, good night") came at 1:19 a.m. from the co-pilot, and the last communication from the transponder was at 1:21 a.m.; there was no ACARS transmission at 1:37 a.m., as scheduled.

- At 2:15 a.m., Flight 370 appeared on a Malaysian military radar, the last known record of the plane's location.

- Sometime after 8 a.m., a satellite over the Indian Ocean picked up the final known transmission from the aircraft, a "ping" or "keep alive" signal that suggests the plane was somewhere along an arc stretching from Kazakhstan to off the west coast of Australia. The plane had enough fuel to travel up to an hour beyond that point.

From what we've learned so far, here are some of the biggest flubs:

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

1. Airport officials didn't check passports against Interpol's database

At least two of the passengers boarded the airplane using stolen European passports — a potential safety problem that could have been avoided if Malaysian airport officials had checked passports against an international database run by Interpol. This failure to cross-check passports against the freely available Interpol list is apparently pretty common outside the U.S. and Europe, and in this case the two passengers — Iranians Pouri Nourmohammadi, 18, and Delavar Seyed Mohammad Reza, 29 — appear to have played no role in the vanished jetliner.

But the failure to check the passenger manifest against Interpol's database is "the starting point of what didn’t happen, and that trail only gets worse," says 737 pilot Chris Manno at his blog JetHead. "If what the rest of the modern world considers essential — airline and airport security — is simply not maintained in Malaysia, what else is not done there?"

2. Malaysia's military didn't challenge or intercept the plane

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Malaysia's first big mistake was not questioning, or maybe even noticing, Flight 370 when it passed over a military base on the country's west coast. By this point, the airplane was far off its scheduled flight path with its transponder disabled — circumstances that should have prompted some reaction from the four-member air defense crew at Malaysia's Butterworth air force base. Ideally, they would have scrambled their U.S.-made F-16s to check out what was going on with the errant flight.

Instead, "the watch team never noticed the blip," an unidentified person with detailed knowledge of the investigation tells The New York Times. David Learmount at aviation news service Flightglobal adds: "The fact that it flew straight over Malaysia, without the Malaysian military identifying it, is just plain weird — not just weird, but also very damning and tragic." Nobody knows if the fighter jets could have saved the airplane, but we would probably at least know what happened to the jetliner and its passengers.

Rohan Gunaratna, a security and terrorism expert at Singapore's Nanyang Technological University, is less surprised. "European and North American militaries and governments respond to such anomalies and aberrations in aviation routes, but many Asian governments don't as they are not paying such close attention," Gunaratna tells TIME. "Even if the government is informed, it may not take the same decisive action."

3. Malaysia kept an international search party in the wrong area for a week

Malaysian military officials discovered the radar contact with Flight 370 on the morning of March 8, after reviewing tapes from the night before. Gen. Rodzali Daud, the head of Malaysia's air force, reportedly was told of the late sighting on March 9. And yet Malaysian officials had an international search party looking on the wrong side of the Malaysian peninsula until March 15.

By the time the government revealed the existence of the military radar sightings and satellite data, aircraft and ships from 14 nations had spent a week in the Gulf of Thailand on what amounts to a wild goose chase, and the hopes of finding wreckage in the Indian Ocean decreased drastically. Now, 26 nations are searching a huge area, aided by about 3 million internet users — including Courtney Love — who are scouring photographs for telltale signs of a wrecked plane.

4. Authorities didn't search the pilots' homes for a week

As new information comes in — or leaks out — about the flight, Malaysian officials are increasingly pointing fingers at the plane's pilot, Capt. Zaharie Ahmad Shah, and co-pilot Fariq Abdul Hamid. Flight 370 changed course after somebody reprogrammed its flight path, something only a trained pilot would know how to do. But police didn't search the homes of Shah and Hamid until March 15. So far, neither pilot is being accused of hijacking the flight, but Malaysian officials are dropping hints — like the fact that Shah had a homemade flight simulator in his house.

Over the weekend, officials started insinuating that the pilot — who has logged more than 18,000 flying hours in the cockpit since joining Malaysia Airlines in 1981 — is an ardent supporter of Malaysian opposition leader Anwar Ibrahim, who was ordered back to prison (on widely discredited sodomy charges) just hours before the flight began.

Anwar is a thorn in the side of the government, but he's "trying to defeat Malaysia's authoritarian regime through elections — not terrorism, let alone revolution," says William Dobson at Slate. "So, to be clear, what we know is that the pilot of MH370 is a fanatical supporter of a nonviolent man who supports a pluralistic and democratic Malaysia." Dobson continues:

If we are engaging in wild theories — and why not, this is Malaysian politics — then why would unnamed police sources be playing up the pilot's political beliefs a week after we are no closer to knowing the truth about MH370? Because the Malaysian authorities' performance during this investigation is a pretty reasonable approximation of what passes for governance in a corrupt, nepotistic regime that long ago lost any purpose besides accumulating wealth and extending its own power. [Slate]

Peter has worked as a news and culture writer and editor at The Week since the site's launch in 2008. He covers politics, world affairs, religion and cultural currents. His journalism career began as a copy editor at a financial newswire and has included editorial positions at The New York Times Magazine, Facts on File, and Oregon State University.

-

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule works

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule worksIn the Spotlight The law is at the heart of the Colbert-CBS conflict

-

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?Today’s Big Question Democrats want to rein in ICE’s immigration crackdown

-

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day