Dirty Love by Andrew Dubus III: Heartache in the wake of a sexual revolution

The novella and three short stories in this collection revolve around characters struggling with empty relationships

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

We like to tell ourselves a happy story about love, sex, and progress. In the bad old days, sexual repression ruled the land, with men and women hemmed in by puritanical mores that imposed draconian courtship rituals and dealt harshly with anyone who dared to defy them. Pre-marital sex, homosexual attractions, adultery, divorce — any of these and many more acts of deviance from traditionalist norms could ruin lives, producing profound suffering and pain, shame and self-loathing.

And then the dawn broke. Artificial birth control, women's liberation, no-fault divorce, legalized abortion, the gay rights movement — all of it and much more brought the breath of freedom and the first tentative steps toward the guiltless enjoyment of sensual pleasure. Some sexual relationships would develop into love and lead to marriage, but others wouldn't, and that was just fine. People were now free to spend much of their teens and 20s — and even 30s and 40s and 50s and beyond — having a series of erotic (and autoerotic) "experiences," treating sex as a pleasant, fun, low-stakes diversion from the careerism that increasingly consumes their lives. What could possibly be the problem with that?

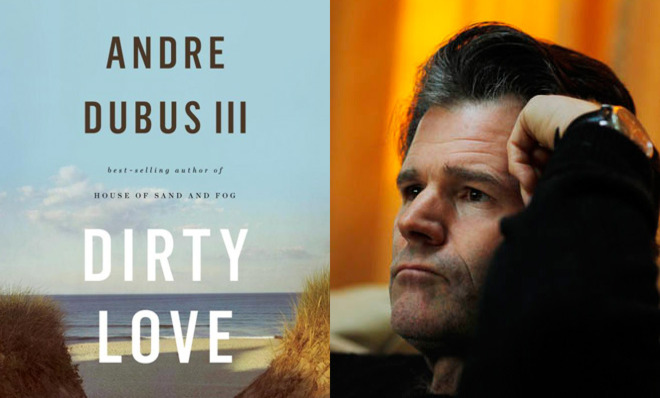

Nothing in Andre Dubus III's Dirty Love indicates that the author is nostalgic for an earlier era of love and sex. Yet his stunningly powerful collection of short stories (really three short stories and one novella) nonetheless focuses a melancholy, sympathetic gaze on some of the new forms of shame and suffering that have come to the fore in the wake of the sexual revolution. We have fewer hang-ups, but we're still lonely. We're freer than ever to choose our own direction in life, but we still feel lost. We've gone a long way toward detaching sex from love, but it hasn't left us more fulfilled. We still feel romantic pain and rejection. We still judge each other and ourselves harshly. We still crave an elusive connection with another — and act in ways, despite ourselves, to sabotage it.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

As he's demonstrated time and again in his previous work (including the bestselling novel House of Sand and Fog and the critically acclaimed memoir Townie), Dubus steers clear of the overweening irony and show-offy knowingness so typical of contemporary literary fiction. His great strength is compassionate, intricate storytelling lightly embellished with exquisitely (sometimes excruciatingly) revealing similes and metaphors. There may be no finer writer working today.

Dirty Love's four stories take place in a cluster of towns on the Massachusetts coast north of Boston (where Dubus himself lives with his family). Central characters from each story make walk-on appearances in others, sometimes as objects of misinformed gossip, giving the book greater unity than a typical collection of stories, though not as much as a novel. The overall effect is to create the impression of a concrete community of people living in close proximity to each other while struggling through life in their own private ways.

In the first story ("Listen Carefully (As Our Options Have Changed)"), a middle-aged man named Mark Welch attempts to cope with the pain of discovering that his wife is cheating on him and has no intention of breaking off the affair. He's a highly controlling project manager who saw his marriage — or rather, his wife — as one of his most important projects. Now that it's failed and his efforts to re-exert control continually backfire, he's cut adrift, wandering like a spectator through his own life.

"Marla" tells the quietly heartbreaking story of an overweight bank teller who after years of loneliness finally finds romance and intimacy in the arms of a pot-bellied, sedentary man-child named Dennis, who invariably hops into the shower after sex, leaving Marla feeling "dirty and like what they'd done was slightly wrong somehow." Dennis is a perfectly decent man who shows Marla genuine affection. But he prefers to spend night after night eating food in front of the TV or playing hyper-violent video games (which conjure a mood of "bruised emptiness" for Marla). As for children, Dennis doesn't want any. Ever. As he explains, "You know I love you, Marl, but do you know how much kids cost? How much attention they need? It's nothing personal, hon. I just can't be bothered with that."

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

The title character of "The Bartender" feels much the same way about children, though he can't manage to express it so forthrightly — not to his young wife, and not even to himself. Robert likes to call himself a poet who merely tends bar to make ends meet while he perfects his craft. But his behavior over the years (shown in a series of beautifully crafted flashbacks) reveals a man who fell in love with poetry in college because it helped him convince girls to sleep with him, and because it allowed him to feel superior to his father, a farmer who sees straight through his son's pretenses. ("You're all talk, aren't you, son? Nothing but talk.")

Robert drifts through life, following his impulses without resistance, falling into bed with whatever waitress or barmaid happens to respond to his roving flirtations. And he stumbles into marriage, too, and into fatherhood. Oblivious to his own recklessness, he barely manages to avoid bringing ruin to everything and everyone he cares about. By the story's close, he's just begun to wrestle with the consequences of his irresponsibility and self-deception, and we're left to wonder whether he's capable of growing out of his seemingly interminable adolescence.

The first three stories are exceedingly accomplished works of fiction. But they are a mere preparation for the book's concluding masterpiece, the 125-page novella that gives the collection its title. At the center of "Dirty Love" is Devon, an angry 18-year-old girl who lives with headphones plastered to her ears blasting gangsta rap and with an aptly named iEverything in her hand, its flickering screen mediating many of her most meaningful social interactions. The story's opening pages are a torrent of disconnected thought-fragments mixing memory, pop culture, and advertising. It's stream-of-consciousness for the age of total media saturation.

It doesn't take long for us to discern that Devon's anger stems in part from some form of online sexual humiliation. As the story unfolds and we get to know Devon's loving great-uncle Francis, her well-meaning but uncommunicative ex-boyfriend, her sweetly passive mother, and her cretinous, alcoholic father, we circle around the traumatic event, catching glimpses of it from multiple angles, but only finally learning the disturbing, dirty details in the story's closing pages.

Devon lives in a world in which teenage boys and girls relate to each other almost entirely in sexual terms. The boys don't crave sexual intercourse so much as quick, easy orgasms — and there's no quicker or easier path to release than a blow job, which the girls learn at a young age gives them a margin of power. A boy named Luke, who barely touches Devon and kisses her only for a few seconds before expecting her to service him, is like "her patient and she was the only one who could cure him." The only problem is that once sexual intimacy has been stripped of any personal, emotional connection, the vessel becomes a matter of indifference. Devon learns this lesson when she discovers Luke in the bathroom at a party, another girl kneeling before him, "his sickness getting healed and it didn't matter who the doctor was... Her power was in every girl, in every girl's open mouth."

A couple-paragraph summary can't begin to convey the richness of the multifaceted tale Dubus tells in this story — about Devon and her oversexed and emotionally antiseptic digital-teenage world, about her nascent online love affair with Hollis (a veteran of the Iraq War she meets on Chatroulette), and most of all about the 81-year-old Francis (a widower, recovering alcoholic, retired schoolteacher, and veteran from an earlier war that has left its own permanent scars).

We come to care deeply about these people because of Dubus' immense skill at conjuring them into being, and his equally formidable talents as a storyteller. But we also care because we recognize them and their problems, their pain, their "dirty love" — and their struggles to rise above their demons and regrets and the tawdriness of their world.

Which is our world.

Damon Linker is a senior correspondent at TheWeek.com. He is also a former contributing editor at The New Republic and the author of The Theocons and The Religious Test.

-

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule works

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule worksIn the Spotlight The law is at the heart of the Colbert-CBS conflict

-

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?Today’s Big Question Democrats want to rein in ICE’s immigration crackdown

-

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day