True Detective's dangerous lies about satanic ritual abuse

The "true story" behind True Detective is all fiction

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

This year marks the 100th anniversary of the filming of The Birth of a Nation, D.W. Griffith's cinematic masterpiece, which introduced a host of revolutionary movie-making techniques to the new art form.

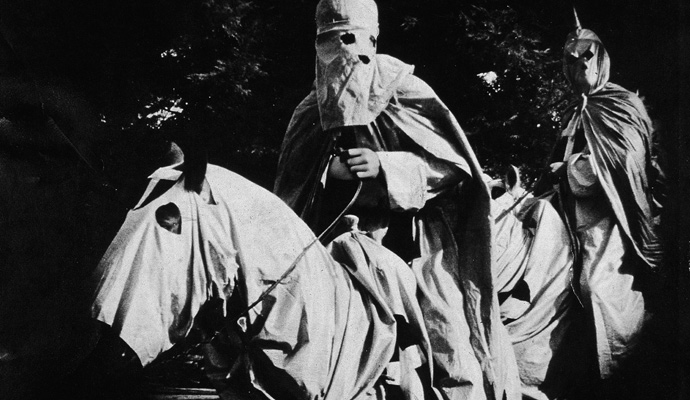

Unfortunately, The Birth of a Nation also introduced millions of Americans to the now-discredited historical theory that the post-Civil War Reconstruction era had been a disaster for the South because it was dominated by abolitionists, freedmen, and carpet bagging politicians. The movie's most deplorable feature was its portrayal of the Ku Klux Klan as playing a critical and admirable role in restoring social order. (When it debuted, the film was entitled The Clansman).

The film exploited moral panic over the supposedly sexually rapacious tendencies of black men toward white women (the black roles in the film were played by white actors in blackface, who engage in various minstrel show-style antics), to the point where the newly-formed NAACP organized protests against it. The Birth of a Nation was a huge commercial success: it was the first motion picture ever shown at the White House, and it's credited by some historians for playing a key role in the revival of the KKK in the years immediately following its release.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Like Leni Riefensthal's more infamous Triumph of the Will, the film raises sharp questions regarding the moral responsibilities of artists toward their material, even, or perhaps especially, when they use that material to achieve aesthetic triumphs.

Such questions are also raised by another aesthetic triumph: HBO's eight-part noir crime drama True Detective. A tour de force of writing, acting, and directing, True Detective sketches a dark vision of a decaying, sinister world, in the midst of which two men try to unravel a mystery that involves the satanic ritual abuse and murder of young women and children.

True Detective is a brilliant, compelling drama — some have gone so far as to suggest it might be the best television series ever — but, like The Birth of a Nation, its plot depends on exploiting a massive distortion of the historical truth, or, less demurely, on transmuting noxious lies about the past into art.

This year also marks the 30th anniversary of the McMartin prosecution, which produced the longest, most expensive trial in the history of the American criminal justice system. That prosecution was dedicated to convicting and punishing the perpetrators of what turned out to be a completely imaginary crime: the satanic ritual abuse of children in a Los Angeles preschool.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

The McMartin case, along with several other similar cases that authorities pursued in the 1980s and early 1990s, ended up being a disgrace to both jurisprudence and journalism, as hysteria and moral panic swept over the nation, leading otherwise reasonable people to discard the most minimal skepticism. As Margaret Talbot wrote in 2001:

When you once believed something that now strikes you as absurd, even unhinged, it can be almost impossible to summon that feeling of credulity again. Maybe that is why it is easier for most of us to forget, rather than to try and explain, the Satanic-abuse scare that gripped this country in the early 80's — the myth that Devil-worshipers had set up shop in our day-care centers, where their clever adepts were raping and sodomizing children, practicing ritual sacrifice, shedding their clothes, drinking blood and eating feces, all unnoticed by parents, neighbors and the authorities.

Of course, if you were one of the dozens of people prosecuted in these cases, one of those who spent years in jails and prisons on wildly implausible charges, one of those separated from your own children, forgetting would not be an option. You would spend the rest of your life wondering what hit you, what cleaved your life into the before and the after, the daylight and the nightmare. And this would be your constant preoccupation even if you were eventually exonerated — perhaps especially then. For if most people no longer believed in your diabolical guilt, why had they once believed in it, and so fervently?

Given the history of profound injustices perpetrated as a consequence of false charges of satanic ritual abuse, it's not unreasonable to expect artists to treat that history with a degree of circumspection. Unfortunately, Nic Pizzolato, the creator of True Detective, has done just the opposite. While Pizzolato's decision to put a "real" satanic ritual abuse cult at the center of True Detective's fictional world might be defensible, his comments to the media regarding that choice are not.

In an interview with Entertainment Weekly last month, Pizzolato responded to a question about the inspiration for the show: "You can Google 'Satanism' 'preschool' and 'Louisiana' and you'll be surprised at what you get." This is clearly a reference to a 2005 child abuse prosecution in Ponchataoula, Louisiana, that generated lurid international headlines about ritualistic Satan worship inside a church, complete with black robes, animal blood, orgies, and pentagrams.

This has since led various media sources to report breathlessly on the "true story" behind True Detective. The problem is that this "true story" turns out to be completely false, at least in regard to all the details regarding Satanic ritual abuse. These were apparently part of a classic atrocity story, invented by the defendants to garner sympathy from jurors — the idea being that the defendants were victims of an unspeakably evil church-based mind control cult, rather than merely being banally evil and not very interesting child molesters.

What sort of moral responsibility do artists have not to exploit, and thereby perhaps propagate, moral panics? The aesthetic power of The Birth of a Nation and Triumph of the Will has not absolved their creators for choosing to exploit racist and anti-Semitic beliefs. Our shameful history of panics and persecutions over the imaginary satanic ritual abuse of children should have been treated by artists as talented as the makers of True Detective as a cautionary tale, rather than as an opportunity for further invidious myth-making.

Paul Campos is a Professor of Law at the University of Colorado. He writes frequently on current affairs. His books include The Obesity Myth, Jurismania, and Don't Go to Law School (Unless).

-

What to expect financially before getting a pet

What to expect financially before getting a petthe explainer Be responsible for both your furry friend and your wallet

-

Pentagon spokesperson forced out as DHS’s resigns

Pentagon spokesperson forced out as DHS’s resignsSpeed Read Senior military adviser Col. David Butler was fired by Pete Hegseth and Homeland Security spokesperson Tricia McLaughlin is resigning

-

Colbert, CBS spar over FCC and Talarico interview

Colbert, CBS spar over FCC and Talarico interviewSpeed Read The late night host said CBS pulled his interview with Democratic Texas state representative James Talarico over new FCC rules about political interviews