How the West can peacefully push Putin out of Ukraine

Russia's president does have a weak spot

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

To figure out what happens next in Ukraine, everybody seems to be putting Russian Vladimir Putin on the couch. What is he thinking by invading and occupying Ukraine's Crimean peninsula? What's going on in his head? The consensus in the West is that the former KGB colonel, safely ensconced in power and traumatized by the collapse of the Soviet Union, is laser-focused (like a chess player, naturally) on rebuilding something like a manageable approximation of the Soviet empire.

There's even a not-so-subtle strain of argument that Putin isn't playing (chess, of course) with his full slate of pieces. Putin's mind is "in another world," not the real one, German Chancellor Angela Merkel reportedly told President Obama on Sunday. Secretary of State John Kerry made a slightly more diplomatic point, arguing on Face the Nation that Putin is acting out of "weakness and out of a certain kind of desperation." He added: "You just don't in the 21st century behave in 19th-century fashion by invading another country on a completely trumped-up pretext."

Acting crazy isn't necessarily irrational in world politics, but actual delusions of grandeur have led even tactically brilliant leaders to great defeat. Why all this matters, of course, is that Putin just blatantly invaded a neighboring nation, ignoring a handful of international treaties and agreements in the process. There are 6,000 Russian troops, and counting, occupying part of a sovereign nation that posed it no threat.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Everybody seems to be asking if the West — and specifically, the world's sole superpower, the U.S. — is willing to push back in any meaningful way. And if so, what will work to keep Putin from carving up Ukraine, and possibly other Western-looking former Soviet satellite states? Almost nobody thinks sending in U.S. armed forces is a great idea — and American presidents never do send troops to Russia's doorstep, as Paul Brandus notes. What does that leave?

Obama has already canceled a trade mission to Moscow and joint U.S.-Russian naval exercises, stopped preparations for an upcoming Group of Eight (G8) meeting in Sochi, convinced the other six non-Russia G8 members to suspend work on the Sochi meeting, and sent Kerry to Kiev to show U.S. support. He has proposed what Kerry calls a face-saving "off-ramp" to Putin — European human rights monitors in Crimea instead of Russian troops.

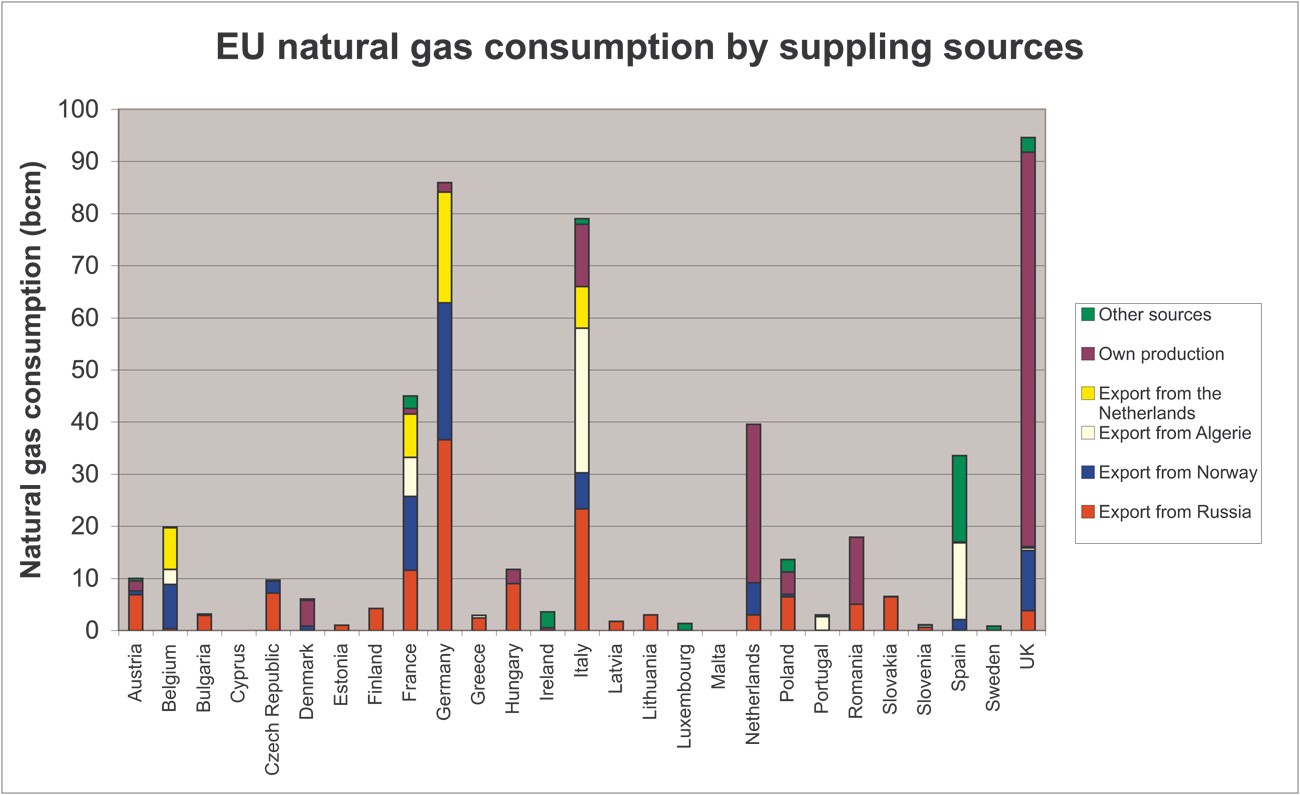

But Obama has also said that Russia will pay some "significant costs" — according to the British government, which agrees with the assessment — if Putin doesn't change course in Ukraine. And suspended G8 preparations hardly meet that threshold. Kerry on Sunday suggested that the U.S. might kick Russia out of the G8 entirely, but Merkel has publicly opposed even such a relatively modest move. This chart, from Statistics Norway in 2007, might help explain why:

Europe still imports a significant amount of natural gas from Russia, and Ukraine gets more than half of its supply from there. But Russia's moves to cut off the gas spigot to Ukraine (and, by extension, Western Europe), combined with increases in natural gas supplies from the U.S. and elsewhere, "have blunted Moscow's weapon," says Steven Mufson in The Washington Post. Ukraine has cut its gas use by 40 percent in five years and diversified its sources. In 2012 Norway's Statoil topped Russia's Gazprom in selling natural gas to Europe.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

If the international gas marketplace has blunted Putin's ability to influence events in Ukraine and Europe, it's also probably the West's best way to make Putin pay for Crimea. The New Republic's Julia Ioffe argues persuasively (and darkly entertainingly) that almost nothing the U.S. and its allies can throw at Putin will deter him from gobbling up Crimea, eastern Ukraine, and the rest of the south.

But the key to reining in Putin may not actually lie with Putin at all.

Michael McFaul, Obama's recently departed ambassador to Russia, suggests that Putin's soft underbelly may be the business interests that have close economic ties with the world, especially Europe. Russia's superwealthy hide so much money in European banks, they almost brought down the country of Cyprus.

If Moscow doesn't back down, "Obama should make clear that its aggression will comprehensively damage all aspects of Russia's relations with the United States," says The Washington Post in an editorial. "Obama should make clear that he will no longer shrink from applying sanctions to Russian leaders and businesses complicit in aggression or human rights violations." Congress is already considering legislation to that effect. The Post's editors say Obama needn't wait:

An expanded list of Russian officials subject to visa denials and asset freezes that was drawn up by the State Department late last year should be immediately approved by the White House. Russian officials in the chain of command of the Ukraine invasion, as well as Russian companies and banks operating in Crimea, should be the next targets of financial sanctions.

The most powerful nonmilitary tool the United States possesses is exclusion from its banking system. Mr. Obama should make clear that if Russia does not retreat from Ukraine, it will expose itself to this sanction, which could sink its financial system. Russia's economy, unlike that of the Soviet Union, is heavily dependent on Western trade and investment. It must be made clear to the Kremlin that the Ukraine invasion will put that at risk. [Washington Post]

If Putin's power really does lie not only in a firm grip on the legislature, media, and various other sources of power, but also a system of oligarchic patronage, the U.S. and Europe have the tools to erode the support of the oligarchs. If a few Moscow-favored businessmen make trouble, Putin can just send them to jail (see: Khodorkovsky, Mikhail) or (allegedly) poison them. But what if a critical mass of Russia's wealthy elite saw their offshore wealth and travel privileges threatened?

No man is an island. That includes Vladimir Putin.

Peter has worked as a news and culture writer and editor at The Week since the site's launch in 2008. He covers politics, world affairs, religion and cultural currents. His journalism career began as a copy editor at a financial newswire and has included editorial positions at The New York Times Magazine, Facts on File, and Oregon State University.