The Air Force still doesn't get it

Undermining the morale of nuclear officers

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

You've read about a cheating scandal involving one fifth of the missile launch officers at Malmstrom Air Force Base in Montana. That brings to mind an image of someone copying answers on a particularly difficult test. Our gut reaction: Nuclear missile crews cheating! That's a huge blow to their integrity. Fire them! Get rid of the commanders! Clean house! And coming on top a drug scandal...

Simmer down a second.

The practice is and has been so widespread that to call it cheating actually misrepresents what's been going on. Every month, officers are tested on multiple subjects and they have to score very highly to retain their rating, as it were. Bad scores reflect poorly on individual units. For three decades, the tests were routinely, commonly treated as group exercises in recall, rather than evaluations. The tests used to be open-book; after all, the book is actually there and would be there when they'd have to use the information in real life. (Everyone seems to have participated. Everyone.) The commanders believed it was more important to foster an esprit de corps and ensure that everyone knew the right answers than to regularly test whether their subordinates' minds were sharp. That this choice was second nature suggests to me that the problem has everything to do with the expectations placed upon the nuclear force and very little to do with their general integrity.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

The tests are administered on a rolling basis, so officers who take them early in the month can pass along tips to others, the former officers said. In other cases, instructors make it clear what the test will focus on, in an effort to raise scores, Weeden said.

Most officers did not seek actual answers and some refused to exchange information about tests at all, Weeden said. The other two former officers said outright cheating was more common.

The missile-safety procedures alone fill two thick binders. A decade ago the test on those procedures was open-book, reflecting the impossibility of memorizing the rules, Weeden said.

But rather than easing with the end of the Cold War, the demands for perfection on tests has intensified in recent years, the former officers said.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

"There is no acknowledgment of human error," said the former officer who requested anonymity.

During a test a few years ago covering missile-launch procedures called "Emergency War Orders," he said, a proctor caught him looking at another officer's paper.

"He confronted me and I denied it," the former officer said. "He may have said something" to the unit's commander, but there was no punishment," he said. [The Los Angeles Times]

In his best-selling new book on a catastrophic accident at an Arkansas nuclear launch complex in 1980, author Eric Schlosser observes of missile repair teams at the time, "they had one of the most dangerous jobs in the Air Force — and at the end of the day they liked to blow off steam, drinking and partying harder than just about everyone else at the base." The esprit de corps among these crews meant that they were "more likely to ride motorcycles, ignore speed limits, violate curfew, and toss a commanding officer in a shower, fully clothed, after consuming too much alcohol." The lethal efficiency of Curtis LeMay's Strategic Air Command remained a trademark of nuclear combat crews, but after the Vietnam War, those who remained in military leadership positions had a different view of discipline. The crews were not immune to efficiently lethal epidurals of drug use and alcoholism, either.

Post 9/11, we don't treat our ICBM missile crews with the same reverence we once did. The threat of nuclear war is far from our minds. In the missile silos of Montana and Wyoming, the crews cycle through exercises. That they'd ever be called upon to turn their launch keys is highly improbable. Besides, we're consumed with terrorism. The Pentagon is consumed with terrorism. The Air Force is distracted by the need to (according to policy) prepare to fight two conventional wars at once and (according to the urgency and particularity of the new enemy) become, principally, a provider of intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance.

The Air Force, through its Personal Reliability Program, still holds missile crews and associated nuclear personnel — about 12,000 in all — to extraordinarily high standards. The highest, actually. Tattling on friends is required. If you're thinking about getting a divorce, you must report it to your commander. If you don't, or if your friend, who knows about it, does not, you could be disciplined or kicked away from nuclear duties altogether. Drugs are forbidden (even where they are legal). Alcoholic consumption within 24 hours of duty is prohibited. So are, one would assume, AshleyMadison.com affairs and recurrent sufferers of anxiety and depression. The PRP reflects a very corporate view of the human brain: One must be, in essence, a white TV father from the 1950s in order for the Air Force to trust you with missile duties. I would much rather the PRP standards reflect the findings of modern neuroscience than the military culture's preconceived notion of nuclear alert duty, and I know that attempting to hold human beings to standards that their surrounding community does not reflect is a near-impossible endeavor, but I find it more comforting than not that the Air Force still recognizes that there is something special about people who work with nuclear weapons.

Here is what the men and women who participate in the PRP get to do. One: They get to obsesses and maintain exceptionally classified information on nuclear war orders and targets. Two: They have privileged access that would tempt them to sabotage the nuclear enterprise somehow, but choose not to do so. Three: They maintain positive control over nuclear weapons — that is, are ready to perform the full launch enable checklist when the right emergency war order is given. Four: They maintain negative control over nuclear weapons — prevent outsiders or insiders from attempting to launch weapons or disable the capability to launch weapons. Five: They follow orders as given by legitimate authorities. And six: They maintain the right frame of mind to do tasks one through five.

As a commander, I'd want your morale to be high. I'd want it to be so high that when the Air Force polls you in private and asks you to describe your morale, you'll say "it's high," rather than, "I sit in a fucking bunker and take impossible tests and get no respect." As a commander, my grades go up when yours do, too. I already know that you have to hold yourself to impossibly high standards. So as a commander, I would be lenient where I could be. I would prioritize the fact that you had to regularly review complicated nuclear procedures more highly than having to pass incredibly difficult tests that require you to recall them.

The Air Force now says it wants to make the PRP "less bureaucratic" and more focused on performance. I don't know how you make nuclear duty any more physically appealing, but the PRP can certainly be less punitive. For one thing, as a stand-alone entity, you might want to merge it with a program of incentives and training that make nuclear duty more attractive. You can structure this PRP-plus to be less a punitive set of restrictions and more a series of services that are made available to Air Force personnel with nuclear duties. If you fail a test, you get tutored, not kicked out. If you voluntarily disclose marijuana use (which, after all, is probably not as debilitating as alcohol consumption), you can avoid punishment. Allow officers to have personal lives; be more mindful of on-duty conduct and do more to build a supportive community off-base. Treat commanders' behavior more harshly than subordinates'.

More of this; less of this. When the secretary of defense says that everything about the nuclear enterprise must be 100 percent perfect (when it never has been), he is essentially admitting to a very different view of the moral problem than the officers themselves. Bureaucracy desires perfection. But we want our nuclear officers to be competent, confident, and honest.

Marc Ambinder is TheWeek.com's editor-at-large. He is the author, with D.B. Grady, of The Command and Deep State: Inside the Government Secrecy Industry. Marc is also a contributing editor for The Atlantic and GQ. Formerly, he served as White House correspondent for National Journal, chief political consultant for CBS News, and politics editor at The Atlantic. Marc is a 2001 graduate of Harvard. He is married to Michael Park, a corporate strategy consultant, and lives in Los Angeles.

-

The ‘ravenous’ demand for Cornish minerals

The ‘ravenous’ demand for Cornish mineralsUnder the Radar Growing need for critical minerals to power tech has intensified ‘appetite’ for lithium, which could be a ‘huge boon’ for local economy

-

Why are election experts taking Trump’s midterm threats seriously?

Why are election experts taking Trump’s midterm threats seriously?IN THE SPOTLIGHT As the president muses about polling place deployments and a centralized electoral system aimed at one-party control, lawmakers are taking this administration at its word

-

‘Restaurateurs have become millionaires’

‘Restaurateurs have become millionaires’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

The recycling crisis

The recycling crisisThe Explainer Much of the stuff Americans think they are "recycling" now ends up in landfills and incinerators. Why?

-

The L.A. teachers strike, explained

The L.A. teachers strike, explainedThe Explainer Everything you need to know about the education crisis roiling the Los Angeles Unified School District

-

The NSA knew about cellphone surveillance around the White House 6 years ago

The NSA knew about cellphone surveillance around the White House 6 years agoThe Explainer Here's what they did about it

-

America's homelessness crisis

America's homelessness crisisThe Explainer The number of homeless people in the U.S. is rising for the first time in years. What’s behind the increase?

-

The truth about America's illegal immigrants

The truth about America's illegal immigrantsThe Explainer America's illegal immigration controversy, explained

-

Chicago in crisis

Chicago in crisisThe Explainer The "City of the Big Shoulders" is buckling under the weight of major racial, political, and economic burdens. Here's everything you need to know.

-

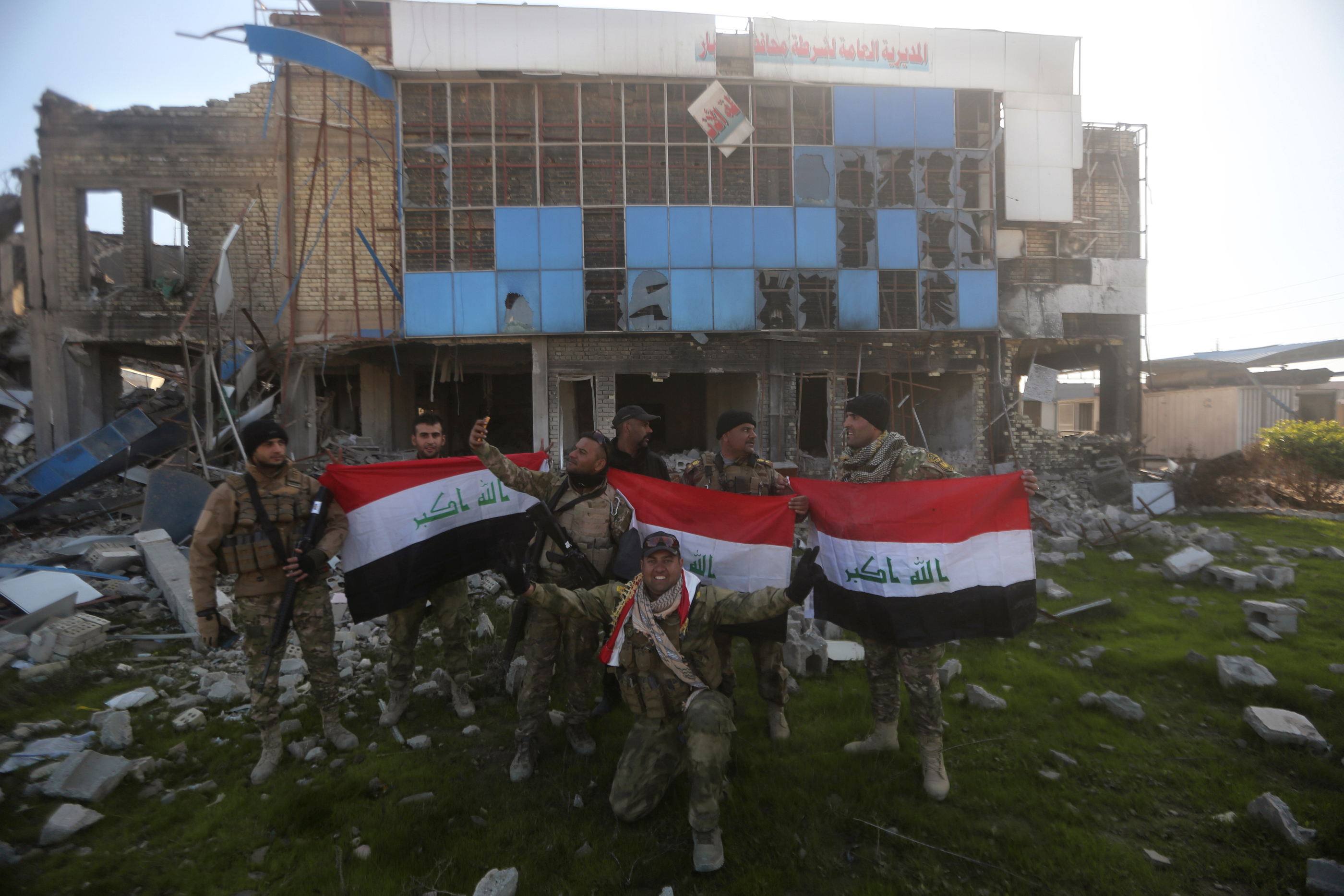

The bad news about ISIS's defeat in Ramadi

The bad news about ISIS's defeat in RamadiThe Explainer The contours of a broader sectarian war are coming into focus

-

America can still destroy the world

America can still destroy the worldThe Explainer The decline of U.S. military power has been greatly exaggerated