The L.A. teachers strike, explained

Everything you need to know about the education crisis roiling the Los Angeles Unified School District

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

The Los Angeles teachers' strike is all about the money.

Okay, that's putting it somewhat pithily. It's about class sizes that are too big, teachers who are underpaid, staffs that are too small, resources that are too few, infrastructure that's crumbling, and low-income and special-needs students who aren't getting enough help. But while brute force spending may not be a sufficient precondition to totally solve all those problems, it's certainly a necessary precondition.

The teachers of the Los Angeles Unified School District feel they aren't getting nearly enough money to address all those challenges. Negotiations between the district and the union, United Teachers Los Angeles, have been going on for months. But when the latest round of bargaining failed to live up to their demands, 30,000 teachers walked off the job last Monday. It's the district's first strike in three decades.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

The Los Angeles Unified School District is the second largest district in the country and accounts for about 9 percent of California students all by itself. Eighty-five percent of those students are below the poverty line, roughly 75 percent are Latino, about one fourth are learning English as their second language, and about one-third perform poorly on standardized testing. The district's schools are dealing with grossly inadequate resources, and class sizes that can top 40 or even 50 students. Teachers and students in the district are up against enormous challenges, to put it exceedingly mildly.

The teachers' union is demanding smaller class sizes, less standardized testing, a 6.5 percent salary bump (retroactive to last year), more support staff (meaning counselors, nurses, librarians, and the like), and hopefully a 2 percent bonus. They believe the district has the money to cover these changes.

Needless to say, the district disagrees, saying meeting the full list of demands would cost $3 billion and lead to bankruptcy.

The district's last counteroffer was a 6 percent raise spread over the first two of the next three years, 1,200 more educators, a full-time nurse at every school, more librarians and counselors, and knocking class sizes down to 35 students max for grades four through six, and to 39 students max for high school. That offer seems to have been made possible by the new state budget from incoming Gov. Gavin Newsom (D), which will beef up state-level education spending.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Union leaders called that offer "woefully inadequate," hence the strike.

A crucial bit of context here is that education spending in California is different from many states. Most of the time, the sizable majority of funding for any one district comes from local property taxes. But in 1978, a state referendum passed Proposition 13, which gutted property taxes across California.

Efforts are afoot to reform Proposition 13 and at least partially rebuild property tax revenues for local government budgets and schools. But for the moment, a whopping 58 percent of K-12 funding in California comes from the state government budget. Only 22 percent comes from local property taxes, and another 10 percent comes from other local taxes.

That's important because it means state budget decisions have a lot more impact, and impose many more limits, on individual districts like Los Angeles.

California's per student spending is about 13 percent below the national average — a dismal level that's pretty much held steady for most of the last 30 years. In fact, when you adjust for different costs of living between states, California ranks 41st out of the 50 states on per student spending. Keep in mind the state has a housing affordability crisis on its hands on top of everything else.

Another wrinkle here is the rise of charter schools. They went from a minor experiment in California in the early 1990s to a full blown industry that educates around 10 percent of the states' K-12 students today. Charter schools receive public funding, but often aren't subject to the same regulations and labor laws and union demands as actual public schools. Whatever you think of the merits of that approach, the fact is whenever a K-12 student leaves a normal public school for a charter school, that student's share of state spending goes with them. Charter schools are in competition with the rest of the school system for resources, which just tightens the squeeze on districts like Los Angeles.

It's probably also worth noting that Austin Beutner — the superintendent of the Los Angeles district, and thus the top official the union is arguing with — is a former investment banker, put in place by a campaign waged by charter schools' wealthy backers in the area.

Add it all up and you can probably see why the Los Angeles Unified School District feels like its back is against the budgetary wall, and why the members of United Teachers Los Angeles feel like they're getting ground into the dirt and our now making maximalist take-it-or-leave-it demands.

This strike could also just be the start.

Other California districts like Oakland and Sacramento are buckling under fiscal strains, with their teachers up in arms. The Los Angeles strike is also just the latest in a string of teacher uprisings from West Virginia and Oklahoma to Kentucky and Arizona — blowback for decades of spending reductions in states across the country, all done in the name of cutting taxes.

The difficult part is that the most sensible solutions to the Los Angeles impasse probably lie beyond both the union's and the district's sphere of influence.

Proposition 13 obviously badly needs to be reformed. California could also try raising taxes and bulking up its spending. But education is the kind of public good that needs to remain stable even when the business cycle wreaks havoc with state tax revenues. Like most states, California has a balanced budget amendment, which hamstrings its ability to spend in a downturn. That means maybe the federal government, which has far more monetary power to deficit spend as it likes, ought to help reinforce state budgets for California and everyone else.

Regardless, someone needs to do something. Because the Golden State's school system is clearly falling apart.

Jeff Spross was the economics and business correspondent at TheWeek.com. He was previously a reporter at ThinkProgress.

-

How to Get to Heaven from Belfast: a ‘highly entertaining ride’

How to Get to Heaven from Belfast: a ‘highly entertaining ride’The Week Recommends Mystery-comedy from the creator of Derry Girls should be ‘your new binge-watch’

-

The 8 best TV shows of the 1960s

The 8 best TV shows of the 1960sThe standout shows of this decade take viewers from outer space to the Wild West

-

Microdramas are booming

Microdramas are boomingUnder the radar Scroll to watch a whole movie

-

The recycling crisis

The recycling crisisThe Explainer Much of the stuff Americans think they are "recycling" now ends up in landfills and incinerators. Why?

-

The NSA knew about cellphone surveillance around the White House 6 years ago

The NSA knew about cellphone surveillance around the White House 6 years agoThe Explainer Here's what they did about it

-

America's homelessness crisis

America's homelessness crisisThe Explainer The number of homeless people in the U.S. is rising for the first time in years. What’s behind the increase?

-

The truth about America's illegal immigrants

The truth about America's illegal immigrantsThe Explainer America's illegal immigration controversy, explained

-

Chicago in crisis

Chicago in crisisThe Explainer The "City of the Big Shoulders" is buckling under the weight of major racial, political, and economic burdens. Here's everything you need to know.

-

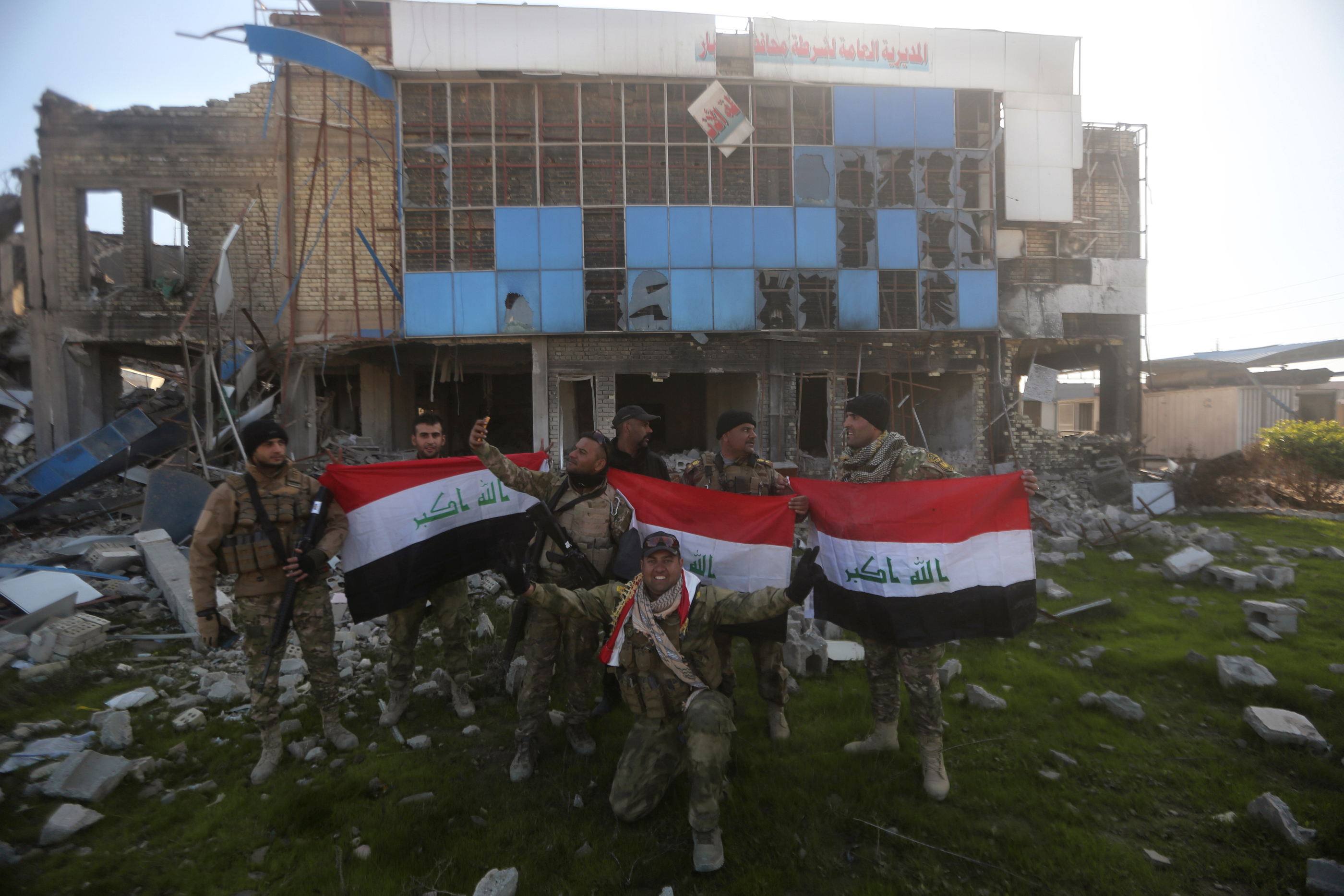

The bad news about ISIS's defeat in Ramadi

The bad news about ISIS's defeat in RamadiThe Explainer The contours of a broader sectarian war are coming into focus

-

America can still destroy the world

America can still destroy the worldThe Explainer The decline of U.S. military power has been greatly exaggerated

-

Why the American military is so hot on laser weapons

Why the American military is so hot on laser weaponsThe Explainer The future is coming at the speed of light