Yes, Netflix really is slower — and it's probably Verizon's fault

An obscure battle over "peering" is likely the culprit for spinning wheels during House of Cards

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

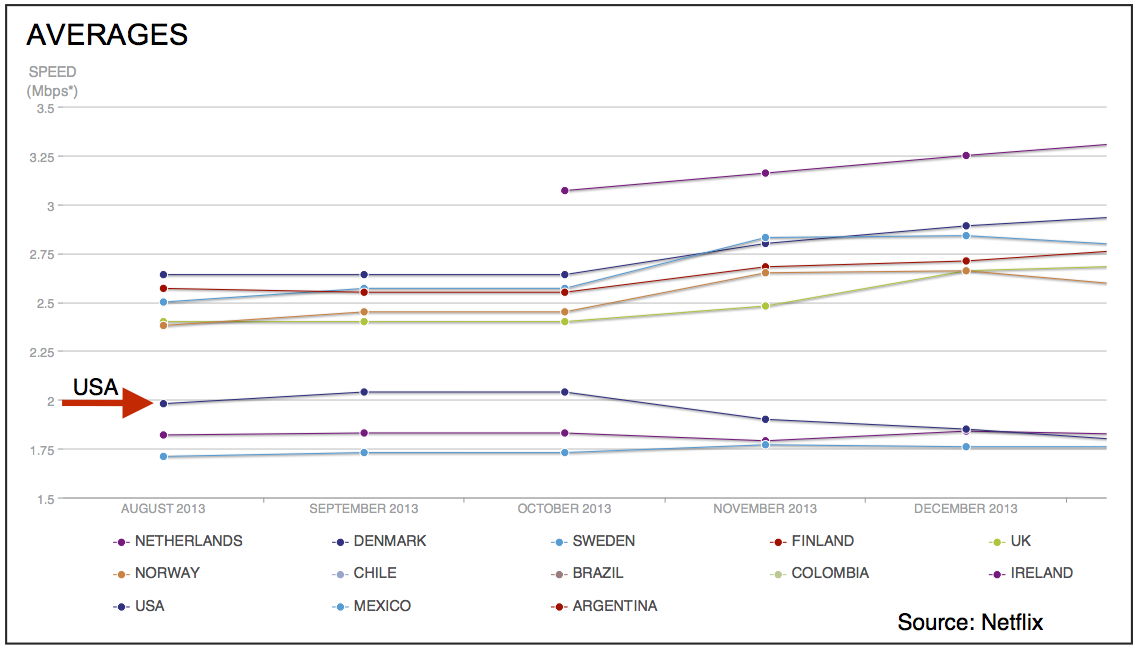

If Netflix has seemed a little slow to load on your laptop or smartphone in recent months, it's probably not your imagination. Average Netflix speed and quality in the U.S. was already pretty subpar, according to Netflix, at about two megabits per second (Mbps) — hey, that was better than Mexico and Ireland — but it's been dropping since last October:

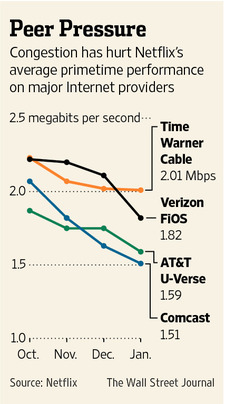

Nobody's really accusing Verizon of outright "throttling" Netflix service — that is, treating streaming movies differently from say, news articles once they're in the Verizon pipeline — but it appears Verizon has found other ways to slow down Netflix traffic without, technically, violating its stated commitment to net neutrality.

Verizon and other large ISPs are in a long-running dispute with Netflix over whether the movie-streaming powerhouse — the single largest user of internet bandwidth, followed by YouTube — should pay extra for its heavy usage, and how. Verizon wants to charge Netflix outright — a big reason it successfully sued the Federal Communications Commission to overturn its net-neutral Open Internet rules.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

The traffic jam now is at the portals connecting Verizon's broadband networks — the ones that go into your house — and the long distance fiber optic networks that carry internet data long distances, according to The Wall Street Journal. Right now, Netflix sends a lot of its data through lines operated by Cogent Communications, and both Cogent and Netflix say Verizon is purposefully keeping some of its portals shut and delaying equipment upgrades to degrade Netflix streaming.

Verizon says it treats all internet traffic equally, but it also is vocally insisting that bandwidth hogs like Netflix pay for dumping so much data into its network. The existing "peering" agreements that govern the interchange of data from one network to another are premised on fairly equal reciprocity — that Verizon will unload about as much data onto Cogent's pipeline to Netflix as Netflix sends to Verizon, say.

With video streaming services, the traffic is heavy and mostly one-way. The slowdown in service started at about the same time Netflix started offering super-HD service to all its subscribers. Netflix has built up its own data-distribution network, but it doesn't want to pay Verizon and its fellow ISPs to hook up directly with their networks.

If you want more technical and legal details, The Wall Street Journal's Simon Constable talks with Shalini Ramachandran, one of the reporters who wrote The Journal's story on the Netflix-Verizon fight:

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Constable also spoke with Cogent CEO Dave Schaeffer, who argues that Verizon, Comcast, and other ISPs restricting traffic at the network interchanges are violating their agreements with consumers to provide internet service at certain speeds:

So what if Verizon isn't your ISP? There's strong anecdotal evidence that Comcast, AT&T, and other ISPs are also somehow slowing Netflix service, either through sins of commission or omission. If you look at the chart above, you'll see that their Netflix performance has dropped since October, albeit at a less dramatic rate. Perhaps more damning is that Google Fiber's Netflix service is actually improving — and Google owns one of the largest network peering facilities in the world.

As MIT Technology Review's David Talbot notes, it's really hard to uncover why Netflix service is slowing down for so many users, since peering agreements and data on network interchanges don't have to be released publicly or reported to the FCC.

This may all seem pretty esoteric. After all, notes Sam Gustin at TIME, "most consumers don't care how Netflix videos arrive on their computer or TV — they just want the service to work." And like it or not, Gustin adds — or even understand them or not — "private peering deals are the new front in the war between the broadband giants and Internet content companies." Netflix viewers are just collateral damage.

Peter has worked as a news and culture writer and editor at The Week since the site's launch in 2008. He covers politics, world affairs, religion and cultural currents. His journalism career began as a copy editor at a financial newswire and has included editorial positions at The New York Times Magazine, Facts on File, and Oregon State University.

-

The ‘ravenous’ demand for Cornish minerals

The ‘ravenous’ demand for Cornish mineralsUnder the Radar Growing need for critical minerals to power tech has intensified ‘appetite’ for lithium, which could be a ‘huge boon’ for local economy

-

Why are election experts taking Trump’s midterm threats seriously?

Why are election experts taking Trump’s midterm threats seriously?IN THE SPOTLIGHT As the president muses about polling place deployments and a centralized electoral system aimed at one-party control, lawmakers are taking this administration at its word

-

‘Restaurateurs have become millionaires’

‘Restaurateurs have become millionaires’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day