6 reasons why U.S. speed skating stalled in Sochi

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

The troubles of this year's U.S. speed skating Olympic team "defy explanation," frets the Christian Science Monitor.

For the first time since many of the current members were born, it looks as if the U.S. won't win a single medal in the sport. In Vancouver, at the 2010 Winter Olympics, the men's team medaled in just about every race; Apolo Ohno dominated the short track heats; Shani Davis won his second consecutive gold for 1,000 meters; and the U.S. showed in all the relay events. The teams took home six medals. Not this year.

Are there intelligible reasons why the U.S. seemed to kind of suck this year?

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

The real reasons are not opaque. In fact, they can be teased out individually.

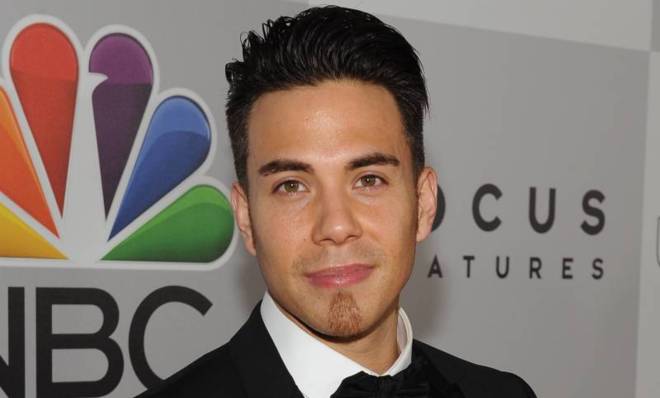

1. Apolo Ohno retired. The dominant figure in short-track since the Turino Olympics in 2006, he brought attention, sex appeal, style, and leadership to the men's team.

2. The best short track speed skater in the United States, Simon Cho, is in Salt Lake City today, not Sochi, because he was banned from the sport for two years after admitting to tampering with the skates of a Canadian rival in 2012. That sounds kind of awful, and Cho, who fessed up, is paying for his choice. The backstory, though, brings us to a third reason:

3. The short track team has been riven by dysfunction. Cho, the last U.S. skater to win a world championship before this Olympics, had a difficult relationship with the former coach of the team, Jae Su Chun. Cho, 22, who was born in South Korea and raised in Maryland, said that Chun asked him to thrice tamper with the skates of the Canadian as an act of retribution for a perceived slight, and that, for a mix of reasons, the Korean-American skater felt compelled to follow orders from an older Korean man.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

A dozen skaters were ready to testify that Chun was both mentally and physically abusive to Cho and others. (He denied the allegations but was forced to resign and later admitted to knowing about the tampering.). Personality conflicts, when interlaced with a slow-to-act national speed skating organization that did not take complaints about health coverage and skater welfare seriously, led many top team members to quit the formal team and train privately. To this day, some members of the short track team don't talk to others.

4. The women's teams were never that good to begin with. This isn't sexism; it's just a quirk of history. Since Bonnie Blair stopped skating long ago, the U.S. men's teams have been better. Katherine Reutter, the most talented American woman to hit the ice since Blair, had to retire from the sport because of enduringly painful injuries. She was just 24 years old.

5. The long-track team, which has done well at recent world cup events, doesn't want to officially blame their new-for-the-Olympics Under Armour Mach 39 skin-hugging, high-tech, aerodynamically zestful suits. But, and I hate to use this Bleacher Report/Adam Schefter phrase, "team insiders" say that the uniforms just didn't turn out to be nearly as good as promised. Long-track skaters mostly skate in straight lines, which increases the relevance of air flow. If the "rear ventilation panels" weren't working as advertised, even a small change, or the perception of it, could be disruptive to the physics of a race.

6. After Vancouver, the Dutch teams upped their game. And the spectacular South Korean-born-now-Russian-citizen Viktor Ahn returned to the sport after a hiatus. Any explanation of the U.S. team's dysfunction must account for the probability that other teams just simply got better.

Marc Ambinder is TheWeek.com's editor-at-large. He is the author, with D.B. Grady, of The Command and Deep State: Inside the Government Secrecy Industry. Marc is also a contributing editor for The Atlantic and GQ. Formerly, he served as White House correspondent for National Journal, chief political consultant for CBS News, and politics editor at The Atlantic. Marc is a 2001 graduate of Harvard. He is married to Michael Park, a corporate strategy consultant, and lives in Los Angeles.

-

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?Today’s Big Question Democrats want to rein in ICE’s immigration crackdown

-

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

Bad Bunny’s Super Bowl: A win for unity

Bad Bunny’s Super Bowl: A win for unityFeature The global superstar's halftime show was a celebration for everyone to enjoy