The Olympics' longstanding gender gap

Ninety years after men on skis first jumped off a hill in a Winter Olympics, women get to try it

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Ski jumping has been a part of the Winter Olympics since the first ever cold-weather Games, in 1924. This year though, the esoteric sport will experience a first: female athletes.

That's because until Sochi, the International Olympic Committee refused to sanction women's ski jumping, repeatedly declining formal petitions that it be included in every Olympics since 1998. For years, the excuse was that there weren't enough participants, and that the sport didn't reach the "technical criteria" to merit inclusion. And though that claim held some truth — the first women's ski jumping world championship wasn't held until 2009 — there was nonetheless an underlying gender bias against including female athletes.

The sport "seems not to be appropriate for ladies from a medical point of view," IOC member and then-International Ski Federation president, Gian-Franco Kasper, said in 2005.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

"I had people ask me if my uterus had fallen out," said Lindsey Van, an American ski jumper, recounting criticism she heard in 2009.

In 2009, Van joined nine other female ski jumpers in suing the Vancouver Organizing Committee for not allowing them to compete. But the British Columbia Supreme Court ruled that, while the exclusion was discriminatory, it had no legal authority to compel the IOC to change course.

A PR fight ensued, with Van participating in a media campaign, Let Her Jump, demanding inclusion.

Under increasing pressure, the IOC in 2011 finally announced it would include women's ski jumping and address gender inequality in a broader sense at the Games. It was a significant victory: Though ski jumping was the cause célèbre, women had long faced widespread discrimination at the Olympics.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Only 13 female athletes competed in the first Winter Games. And even until the 1990s, female athletes comprised less than one-quarter of all participants.

A large part of the problem was that, like ski jumping, many sports remained male-only. It wasn't until 1991 that the IOC mandated all future events be open to both genders — but with a caveat that grandfathered events from the original Games be exempt. Hence bobsledding, an event held every year since the inaugural 1924 Games, didn't include a female component until 2002.

For decades, the same trend marred the Summer Games as well.

Women couldn't compete in the marathon until 1984, and they only got all the same track events as men in 2008. Why? A decades-old myth about women's frailty. As David Epstein, author the The Sport Gene, pointed out, all women's track events longer than 200 meters were dumped after the 1928 Olympics because of a pernicious rumor about women collapsing after one race.

"This distance makes too great a call on feminine strength," The New York Times remarked at the time.

Erroneous medical concerns aside, there's also a troubling social stigma attached to female sports that aren't considered inherently feminine. It's why more attention (and airtime) is devoted to covering women's figure skating than, say, bobsledding. And it's why some suggested, after the last Olympics, that women's ice hockey be dumped from the Games.

So even with women's ski jumping finally making the leap into the Games this year, the "women shouldn't be here" notion hasn't disappeared.

"I'm not a fan of women's ski jumping," Alexander Arefyev, Russia's men's ski jump coach, said recently. It's a difficult, dangerous sport, he said, adding that women "have another purpose — to have children, to do housework, to create hearth and home."

Still, times are indeed changing. Only one sport, Nordic Combined, remains exclusive to men, and then only because it contains a ski jumping portion. Eventually, that, too, will change.

Jon Terbush is an associate editor at TheWeek.com covering politics, sports, and other things he finds interesting. He has previously written for Talking Points Memo, Raw Story, and Business Insider.

-

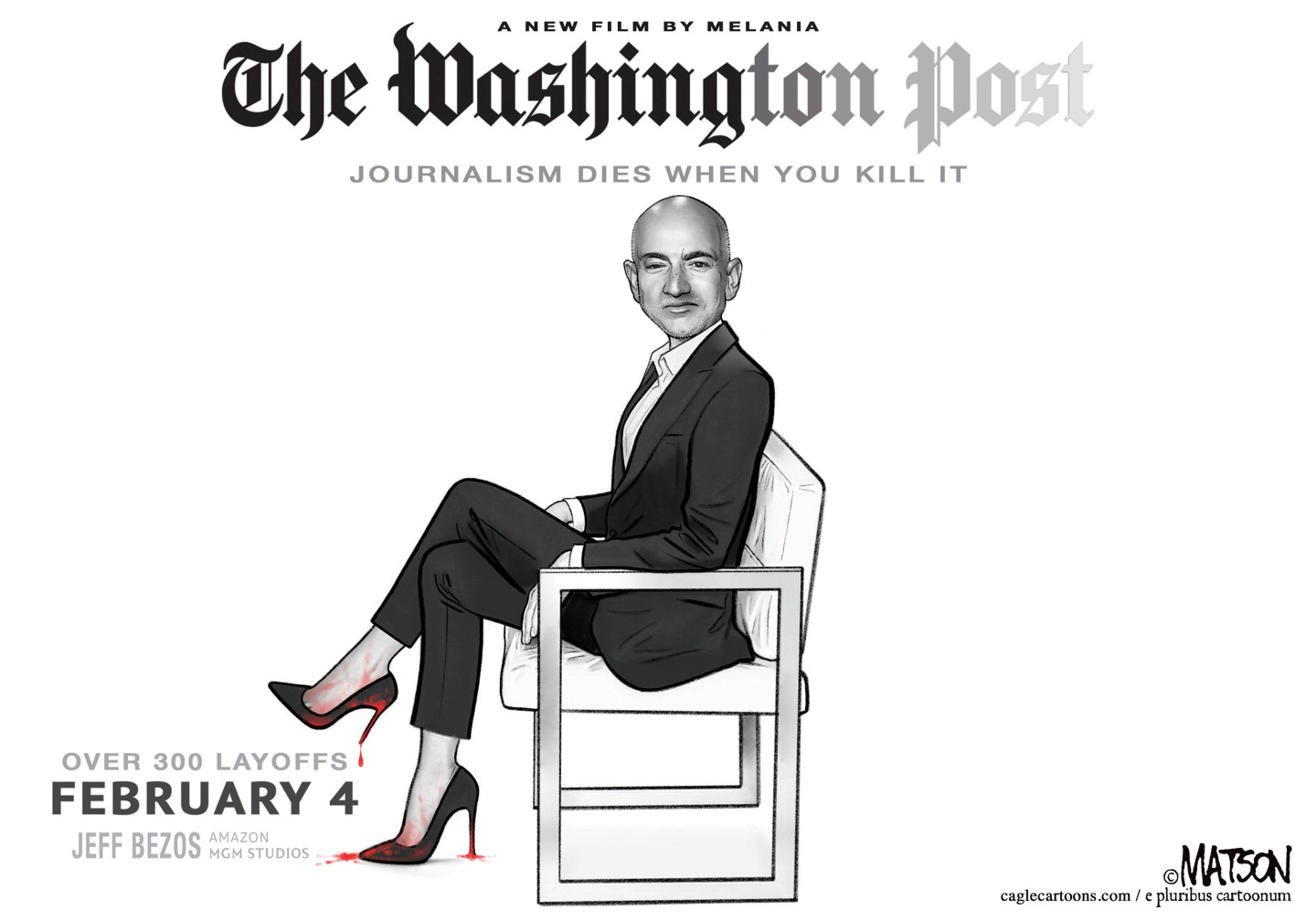

5 cinematic cartoons about Bezos betting big on 'Melania'

5 cinematic cartoons about Bezos betting big on 'Melania'Cartoons Artists take on a girlboss, a fetching newspaper, and more

-

The fall of the generals: China’s military purge

The fall of the generals: China’s military purgeIn the Spotlight Xi Jinping’s extraordinary removal of senior general proves that no-one is safe from anti-corruption drive that has investigated millions

-

Why the Gorton and Denton by-election is a ‘Frankenstein’s monster’

Why the Gorton and Denton by-election is a ‘Frankenstein’s monster’Talking Point Reform and the Greens have the Labour seat in their sights, but the constituency’s complex demographics make messaging tricky