What not to do in a morgue

My first job required me to handle cadavers, and I made a big mistake

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

THE VICTIM OF the first big mistake I ever made was a gentleman to whom I had never been properly introduced but who was possessed of three singular qualities: He was alone in a room with me, he was without his trousers, and he was very, very dead.

It was the winter of 1962. I was 18 years old and had taken a year off before going up to Oxford University. I also had a girlfriend far away in Montreal, and in the superheated enthusiasm of my puppy love, I had promised to visit her. The fact that I then lived in London and she 3,000 miles away meant that fare money had to be amassed: I had to get a job, and one that paid well enough to allow me to get away to Canada as quickly as possible.

London had two evening papers back then, the News and the Standard. It was in the classified columns of one that I spied the advertisement: "Mortuary Assistant required," it said. "Eleven pounds weekly... Some basic knowledge of human anatomy an advantage, though not essential. Telephone Mr. Utton, Whittington Hospital, Highgate."

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

The mortuary, if not perhaps especially congenial, certainly was well-fitted to my interests. I had just passed, and rather well, my A Level examinations in chemistry, physics, and zoology; for the latter, I had dissected on the slab just about every imaginable type of creature, from amphioxus to zebra. Well, perhaps not zebra, but certainly very many mammals, including rabbits aplenty. And believing that a human is basically a very large rabbit, minus those ears and tail, prompted me to pick up the Bakelite telephone on our hall table and call Mr. Utton.

He seemed surprised. Pleased, too, for it turned out no one else had applied for his job. "Necrophobia," he whispered darkly. "A puzzling failing." I explained to him my sanguine notion of man's comparability to a big rabbit; he laughed, and wondered aloud why more people didn't think that way. I told him that I was rather more interested in the money than the biology; he responded that in addition to wages, he paid a per-body bonus of four shillings, and that a quick worker could soon be in pretty decent funds. "All these London fogs," he remarked. "They're killers. Bodies just pile up here."

He hired me, more or less on the spot. The pathologist assigned to work on the bodies I would prepare was a German, and she was named Fleishhacker, which sounded to Mr. Utton as though it should mean butcher, but actually didn't.

Er — "bodies which I would prepare?" I enquired, as lightly as I could. "Oh, you'll get the hang of it," said Mr. Utton.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

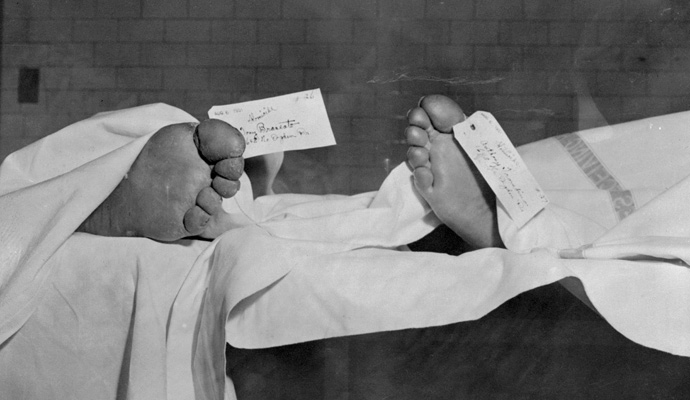

THE CADAVERS THEMSELVES I didn't mind. Each morning a new offering of corpses lay in serried ranks in the freezer, each body fresh from a hospital bed upstairs. My allotted task was to heave them out one at a time, wheel them onto the autopsy slabs, and "prepare" them, as Mr. Utton had rather elliptically suggested.

Perhaps you won't want to know too much about what preparation involved. I'll just say this: If you can accept the basic premise that Frau Fleishhacker's task was to poke around her customers' insides to establish what made each take their leave of us, then I was the chap who opened the various doors to allow her to do so. I made lots of long incisions, cut off lots of things, and used a high-speed Skil saw for the trickier bits (required, for instance, if her Frau-ship ever needed to inspect a brain).

To tidy things up after the autopsy was over, I developed a very adequate blanket stitch, which impressed my mother no end. By the end of each procedure, the bodies looked as good as new, and I also took pride in dressing my charges as nicely as I could, if the relatives had left clothing.

In the interests of full disclosure I should add that I was also persuaded to commit a series of small crimes during my sojourn at the hospital. I stole pituitary glands. About a hundred of them over the months. A research hospital had need of them — pituitaries produce a multitude of hormones, including the one that makes us grow, and I proved myself quite adept at finding them. Each time I collected a jar full, a furtive man in a white coat would come around to collect them, handing over a five-pound note in exchange.

All this may have been a mistake of judgment. It was not, however, the Mistake. That came a month into my employment when a couple of attendants wheeled into the mortuary the lifeless and, except for his bare feet, rather well-dressed corpse of an elderly, white-haired man. By this time such a delivery was quite routine: I had already had many similar encounters with the lately dead. But this fellow was different, mainly because he had a large tag tied around his big toe. On it was written a question mark and in large letters the word LEUKEMIA.

I WAS ALONE in the building at the time of the delivery, and I wasn't immediately sure what to do. But a bit of riffling through Mr. Utton's desk eventually fetched up a tattered old manual describing what to do in the event of discovering gunshot wounds, for example, or upon finding an eruption of angry-looking and possibly infection-laden spots on a corpse. It offered me a single line of advice on leukemia: "Remove femur," it said, "and send it for examination by the laboratory."

The femur, the longest bone in the human body, was quite tricky to remove — think of deboning a chicken, only much bigger and stiffened with rigor — but after 10 minutes of cutting and twisting and yanking, the bone came free, and I put it in a bag and sent it on its way to the laboratory upstairs. They would examine the marrow, I imagined, and determine with precision the cause of the old man's passing.

It was approaching lunchtime when I had the elderly gentlemen blanket-stitched back to normal and his clothes back on. He looked in pretty fair shape, except that his leg, unsupported by any internal skeletal scaffolding, kept flopping off the table. No matter how often I pushed it back up, it always contrived to free itself and flop off toward the floor.

It was at this moment when the undertaker arrived. He was called Sid, and when he saw the pendulum swinging of the boneless leg, he displayed what I can best describe as an animated vexation. He declared vehemently that he was not effing taking that body with that effing leg, or words to that effect.

What to do, I asked. "Not my effing problem, mate," he returned. But then, taking pity: "Tell you what. I'm just going for me dinner. Be back in an hour. Just go and find something to stiffen up the leg, put it in the old bugger, and then I'll be back at 2. Sound like a plan?"

Nothing inside the morgue seemed suitable for stiffening up a dead man's leg. Maybe outside. It was November, cold and raining. Lying on the ground there just happened to be a drainpipe made of galvanized zinc, about 3 feet long, 2 inches in diameter, and apparently doing nothing useful, like draining. That might do the trick, I thought.

Somewhere in the back of the mortuary I remembered a vise, and I had the electric saw that I employed from time to time. Clamping down the pipe, I applied the saw to a mark that I had made on its upper 14 inches, and after a deafening sound and a cascade of sparks, a rod the length of my gentleman's thigh bone dropped onto the floor.

I took off his trousers, undid my stitching as quickly as I could, jammed the drainpipe between pelvis and patella, and noted with pleasure and relief that the afflicted leg shot out like a ramrod. I hurriedly stitched the gentleman's wound back up, dragged up his pinstripes, fastened his belt, and zippered his fly.

Just in time. Sid, now well-lunched and with the smell of beer about him, returned promptly, cast a professional eye on the client, allowed as how I had done a bang-up job, signed my piece of paper, and wheeled my man to his waiting Daimler, dropped him into the coffin in the back, and tamped down the lid.

THE NEXT DAY, around noon, there was a telephone call. Mr. Utton answered it, his replies couched in tones of gathering astonishment. As he slammed the receiver down, he turned to me. "That," he said, "was the undertaker. You dealt with an elderly gentleman yesterday morning?" he inquired. "Well, there was a problem it seems."

He waited for a second, as the hairs rose on the back of my neck. And then he continued. The gentleman wasn't buried. He was cremated.

I got it, in a sudden grisly moment. In my mind's eye I could see it all unfolding, second by ghastly second. The melancholy gathering at the columbarium. The quiet words of comfort from the black-clad minister. The coffin, decked with flowers, poised on its rollers. The vicar, all comfort offered, pressing a hidden button in the recesses of his pulpit. A pair of velvet curtains swishing aside. The coffin beginning to move down that long dark tunnel of the oven, a blaze of light, a roar of blue flame, the swift closing of the steel doors, and then the congregation standing, muttering platitudes, its principals offering thanks to the priest, and the others slowly filing out among the pews. And then, loudly, from within some mysterious somewhere — an all-too-audible sound. A clunk. A harsh metallic clunk. Next: an exclamation. A surprised exchange of voices from among the unseen workers: "Hello," says one. "And what might this be?"

Fourteen inches of red-hot galvanized zinc, raked out where only 3 pounds of warm bone ash had ever been expected. An immeasurable surprise that prompted much anxious discussion among the relatives, once the sheepish crematorium manager explained what had happened. There was some wailing. Suggestions of complaints. Lawsuits, even. But then after some few moments, one of the uncles in the group tried to make light of the affair, with remarks that went along the lines of, "Old George! I never knew he had it in him!" A drainpipe. Much distress. Then black humor.

But Mr. Utton took it much less lightly. He turned to me with rage on his face and lumbered at warp speed across the room. With a flourish he unlocked a cupboard and pointed down to a quiver full of rods. "Look here," he said, almost pulling me by the earlobe. "Chair legs," he said. "White pine. Turns to ash in a second." He spat in disgust, and clumped off back to his office, grumbling as he exited. "Don't make that mistake again."

And no, I never did. Three months and 50-odd cadavers later, I was safely on the steamship to Montreal.

This article is adapted from one that was originally published by LaphamsQuarterly.org. ©2013 by Simon Winchester. Reprinted by permission.