Spike Jonze's Her is actually a terrible movie

Her can be seen as a response to Lost in Translation. And the comparison does Jonze no favors.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Spike Jonze's Her, which has ridden a wave of near-universal critical acclaim to nab five Oscar nominations, including for Best Picture, offers a quirky twist on an old story: Boy meets operating system; boy and operating system fall in love; operating system leaves boy to plumb depths of consciousness beyond human comprehension.

The movie has been praised for its timeliness and topicality, capturing the anxieties of an era in which we spend less time gazing into each other's eyes than into glowing screens of varying sizes. In a gushing review at The New Yorker, Anthony Lane wrote, "Who would have guessed, after a year of headlines about the NSA and about the porousness of life online, that our worries on that score — not so much the political unease as a basic ontological fear that our inmost self is possibly up for grabs — would be best enshrined in a weird little romance by the man who made Being John Malkovich and Where the Wild Things Are?"

But beneath Her's sci-fi premise is a more conventional story about a man (Theodore Twombly, played by Joaquin Phoenix) recovering from the dissolution of his marriage. For all of Jonze's preoccupations about the digital age, for all the implications of spending the bulk of our time interacting with disembodied voices, the movie's heart — if that is not too quaint a metaphor — is a tale of love, loss, and renewal.

Article continues belowThe Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

As a result, many have speculated that Her is a response to a movie with a similar plot, aesthetic, and Pitchfork-approved soundtrack: Lost in Translation, which was directed by Jonze's ex-wife Sofia Coppola. The latter film follows a young woman (Scarlett Johansson) who is drifting away from her husband, a weaselly, shallow, distracted character who has long been rumored to be a stand-in for Jonze himself. But instead of finding solace in the figurative arms of a computer program, she develops a deep, if platonic, relationship with Bill Murray.

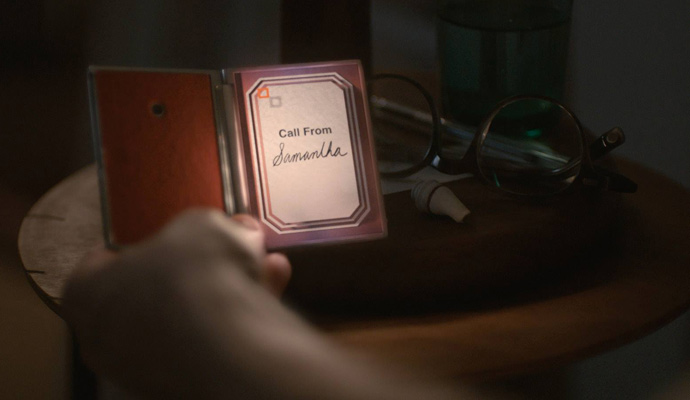

Lost in Translation is set in Tokyo, while Her is a vision of a future Los Angeles that both sprawls and rises like Manhattan, a feat achieved, with alternating degrees of success, by splicing footage of L.A. with Shanghai. (For young American filmmakers, apparently nothing evokes alienation like an Asian megalopolis.) Further entwining the two movies is the casting of Johansson in Her as Theodore's love interest, the operating system Samantha. (This is either purely coincidental, or suggestive of a surrogate scheme that would be far too knotty to untangle here.)

The point is not to delve into the private lives of Jonze and Coppola, or to examine whether, as David Edelstein at New York put it, "Her is an admission of [Jonze's] obliviousness and a lament for it." Rather, the movies are so similar that the comparison offers a useful instruction for why Her fails as a movie on a fundamental level.

Lost in Translation is a triumph of oblique storytelling. The characters say one thing — or often, nothing at all — while the camera says another, conveying rich undercurrents of meaning. Johansson and Murray may be joking about starting a jazz band or silently sharing a cigarette at a karaoke bar, but what is actually happening beneath these banal surfaces is exhilaratingly apparent. This method finds its greatest expression in the famous last scene, in which Murray and Johansson tearfully part with words that can't be heard by the audience. The scene is little more than a street in Tokyo, two actors, and a kiss, which allows the film to achieve both a huge emotional payoff and a kind of cinematic purity.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

In contrast, Her is drowning in words — and what vapid words they are. Because Samantha has no face — no downcast eyes to hint at deeper feeling, no quivering lips to express an inner trembling — she is maddeningly verbose. While more physically expressive, Theodore also becomes trapped in this cage of words, and their relationship is defined by the blunt vocalization of every urge and emotion: I'm depressed, I'm horny, I'm happy, I'm jealous, I'm annoyed, I'm in love.

It doesn't help matters that Jonze is constantly stuffing trite epiphanies into his characters' mouths. A few samples: "The past is just a story we tell ourselves"; "We are only here briefly, and in this moment I want to allow myself joy"; "I can feel the fear that you carry around and I wish there was something I could do to help you let go of it, because if you could, I don't think you'd feel so alone anymore."

Sorry, but this is Velveeta-grade cheese. Her is full of these treacly moments, such as when poor Joaquin Phoenix is forced to frolic in public as Theodore's relationship with Samantha blooms, an emo-adolescent vision of happiness that in no way resembles what being in love looks or feels like. Even the humor — a foul-mouthed video game avatar, a joke about data that is too silly to repeat here — is of the cutesy variety. At one point, a ukulele makes an appearance.

None of this would be even worth mentioning were it not for the glowing reception Her has received in the mainstream press, which could very well land this mawkish mess an Oscar for writing, of all things. But perhaps we shouldn't be too surprised, since mawkishness is having something of a moment in American culture, popping up most egregiously in the more recent films of Wes Anderson, but also in fashionable literature and broad swathes of indie rock music.

This is the art of the hipster, which is to say that there is a lot of style, but the substance is missing. Theodore's mewling would hardly be noticed if it came from, say, a teenage vampire, instead of a thirty-something male in high-waisted pants, oversized glasses, and an interesting mustache. Coppola herself has been tagged with that admittedly loaded term, accused of a film-school chic that relies heavily on borrowed forms that are lacking in depth. But there is real warmth beneath Coppola's cool veneer, which is the opposite of what can be said about Her's vivid orange-and-red palette.

But as usual, Her inadvertently characterizes itself better than any critic could. The movie opens in Theodore's office, where he is among a dozen employees charged with ghostwriting letters for other people. The letters themselves are little monuments to hackneyed prose, a nod to the emptiness of Theodore's life and a trenchant critique of a hyper-networked society that has forgotten how to be intimate. Or so the audience thinks, because it turns out that the letters are supposed to be genuinely touching! Indeed, before Samantha discovers her inner Beckett and leaves Theodore to explore the "spaces between the words," she sends a selection of his letters to a book publisher, who compiles them in a beautiful volume.

And that is Her: A lovely object full of Hallmark sentiments.

Ryu Spaeth is deputy editor at TheWeek.com. Follow him on Twitter.