The Great Firewall of China has a pretty big crack

State censors apparently accidentally shut down the internet for most of China on Tuesday. That's only the half the story.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

On Tuesday, a pretty mysterious thing happened on the internet. The short version certainly grabs your attention: At about 3:15 p.m., China time (yes, China has only one time zone), the firehose of almost all China's internet traffic poured into a small company in Cheyenne, Wyo., crashing its servers in less than a millisecond and shutting down the internet for most of China's 500 million users for about eight hours.

"I have never seen a bigger outage," Heiko Specht, an internet analyst at Compuware, tells The New York Times. "Half of the world's internet users trying to access the internet couldn't."

How this happened is sort of an open question. Chinese media suggested a massive hack by anti-government activists overseas. But outside of China, internet experts are glomming onto a different theory: China's vast array of human and machine-based internet censors, known collectively as the Great Firewall, messed up, big time.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

The blackout worked sort of like this: When anyone in China tried to visit a website ending in .com, .org, and .net — .cn was unaffected — they were redirected to internet addresses owned either by Sophidea, a mysterious company registered in Cheyenne (though its servers could be anywhere), or Dynamic Internet Technology (DIT), a censorship-evading tech firm founded by a member of Falun Gong.

The main thing DTI and Sophidea appear to have in common is that they both help web users get around virtual blockades like China's Great Firewall or Iran's "Filternet."

Presumably, experts say, China's censors were trying to prevent people from accessing those sites. So what happened to the mighty Great Firewall of China? Most likely, human error. "The rule was supposed to be, 'Block everything going to this IP address,'" Nicholas Weaver at UC Berkeley's International Computer Science Institute tells The Washington Post. "Instead, they screwed up and probably wrote the rule as 'Block everything by referring to this IP address.'"

The humans caught the error pretty quickly, according to a timeline from Chinese web monitor GreatFire.org. It took up to eight hours to restore service because humans had to manually flush the DNS caches at internet service providers around China.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

That's the risk of having a huge, centralized internet censorship regime: Any error can have massive consequences, especially in the nation with a huge percentage of the world's web surfers. So why bother? "The Chinese authorities put a premium on control," says Nicole Perlroth at The New York Times.

Using the Great Firewall, they police the internet to smother any hint of antigovernment sentiment, sometimes jailing dissidents and journalists; they blacklist major websites like Facebook and Twitter; and they block access to media outlets like The New York Times and Bloomberg News for unfavorable coverage of the country's leaders. [New York Times]

And that's the biggest crack in China's Great Firewall. Products like DIT's FreeGate can pretty easily shuttle interested Chinese around the firewall into the unrestricted world of the global internet. But information will reach China even if the Great Firewall manages to kneecap such services.

Bloomberg and The New York Times were blocked in China for reporting about the massive wealth accumulated by China's leaders and the ways that wealth was acquired. This week the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists released a big report, years in the making, detailing the secret offshore bank accounts of thousands of Chinese, including close relatives of China's top leaders. Britain's The Guardian was added to China's blacklist for its article on the ICIJ report.

But if you're curious about who in China is stashing their money in the Caymen Islands, you can read about it in the Hong Kong-based South China Morning Post.

Peter has worked as a news and culture writer and editor at The Week since the site's launch in 2008. He covers politics, world affairs, religion and cultural currents. His journalism career began as a copy editor at a financial newswire and has included editorial positions at The New York Times Magazine, Facts on File, and Oregon State University.

-

Political cartoons for February 9

Political cartoons for February 9Cartoons Monday's political cartoons include 100% of the 1%, vanishing jobs, and Trump in the Twilight Zone

-

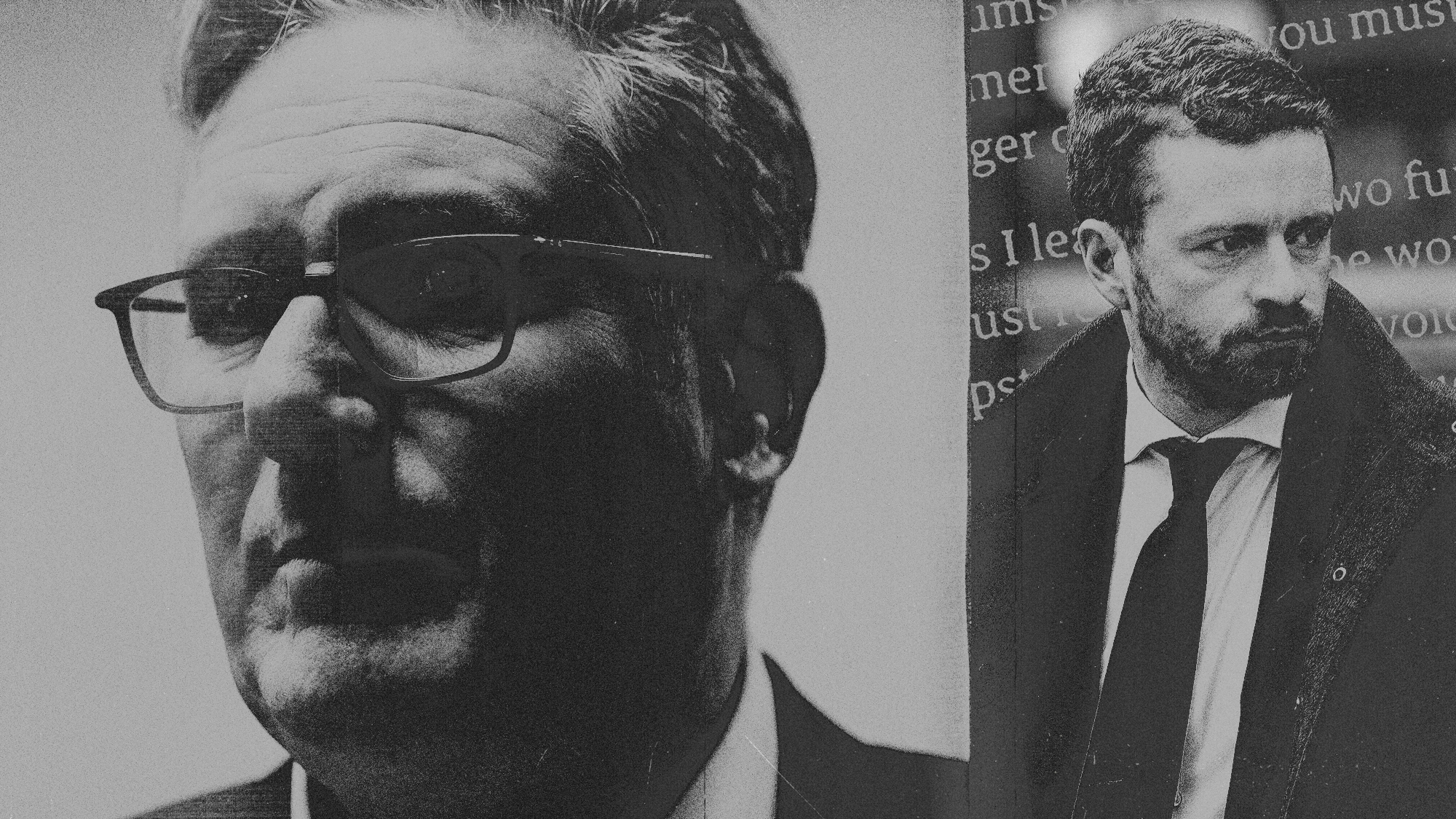

Who is Starmer without McSweeney?

Who is Starmer without McSweeney?Today’s Big Question Now he has lost his ‘punch bag’ for Labour’s recent failings, the prime minister is in ‘full-blown survival mode’

-

Hotel Sacher Wien: Vienna’s grandest hotel is fit for royalty

Hotel Sacher Wien: Vienna’s grandest hotel is fit for royaltyThe Week Recommends The five-star birthplace of the famous Sachertorte chocolate cake is celebrating its 150th anniversary