The man who hid in an airplane bathroom

Habib Hussain sold his field in India for passage to Saudi Arabia and dreams of money and status. He came home as a stowaway.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Humsari Hussain turns away from the small, barren patch of land that she and her husband once owned near the two-room house they still live in. The patch is roughly the size of a tennis court, though once it had seemed to be enough. Surrounding it are well-demarcated rectangles of land owned by neighbors, where cabbages, sugar cane, and wheat are in varying stages of fruition. The patch is barren because the new owner has not worked it yet. Children from nearby homes use it as a playground. They have abandoned the hopscotch squares they etched on the hard brown earth and will soon switch to cricket.

This land once kept Humsari's family fed and was, for a poor family such as hers, the umbrella for a rainy day. Her husband, Habib Hussain, grew up working it. As did his father and his father's father. Then he sold it. For a dream.

"It was our mistake," says his wife. "We made a big mistake, which we are paying for." Her voice chokes up and her eyes fill with tears. Then she gets agitated and begins to shriek, looking at me, though the person she seems to be speaking to is herself. "We were cheated," she says. "We didn't do anything wrong. We didn't do anything wrong." Her two small children tug at her knees, consoling her.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Habib sold their land so to pay for his passage to Saudi Arabia. The strategy had seemed foolproof. Habib would leave his home and his family and his village and travel a great distance in the belief that — like so many Indian men before him — he would earn enough money to return a man worthy of admiration.

Instead he changed his family's fortunes in ways he could not foresee. Then he escaped, in a most unusual way, and in the early winter of 2010, Habib Hussain was briefly a footnote in the national conversation. His face, bearded and drawn, flashed on the television and in the newspapers, not as a symbol of a successful man of the world, but of something else.

More from The Big Rountable: Kill me now

It is not difficult to imagine the appeal of seeking one's good fortune in a place far from Kundarki, the village of some 26,000 souls where Habib Hussain lives.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Kundarki is about 100 miles northeast of New Delhi, in the state of Uttar Pradesh, India's most populous province. Its market street is so narrow it does not allow for two-way traffic. The ground is half-hardened sludge. Sewage spills over onto the path, where it mingles with wet earth and is carried on by cycles, motorbikes, and rickshaws. Lines of grocery stores, stationery shops, and clothing sellers face each other along the route. Lamb and mutton carcasses hang from shop fronts, where flies buzz in circles around the suspended meat, like satellites. As buyers line up in front of the butcher shops, street dogs, their legs as grimy as the lane, bark at their rivals for a bone.

What little work there is to be found in Kundarki is in the fields, where Habib Hussain toiled. But for 20 years, Indian agriculture had been in a free-fall, wreaking such human devastation in the interiors of north and central India that, according to a report by the National Crime Records Bureau, between 1995 and 2010, a quarter of a million Indian farmers committed suicide. Many poor Indian farmers and sharecroppers left for the cities. Millions of others, drawn by stories of the money to be made for those willing to journey to the Gulf, headed overseas, as many Indian men have since the oil boom of the 1970s and 1980s.

Habib Hussain was better off than most people in Kundarki in that he owned his own land. The land yielded little; its worth was in its value to a buyer, and even that was not a lot. But selling it would allow him to afford his airfare, the cost of a visa, and the fee charged by an agent who would make his passage possible. Luckily, or so it appeared, the agent was a relative — Imran, his sister's husband.

Imran himself had made the journey. He had left behind a small farm and traveled to Saudi Arabia where, for three years, he worked for an Arab sheikh. When he returned, in 2008, Imran was able to set up a shop with a photocopier, a fax machine, stationery items, and a telephone booth with long-distance calling capability. Habib saw how Imran had become a man of respect in his village. Imran bought a new Maruti car for himself and a Hero Honda motorbike for his younger brother. Imran began scouting for people who wanted jobs in Saudi Arabia as laborers, coolies, shop workers, electricians, plumbers, and carpenters. He became the local manpower consultant for the Middle East. Habib heard that Imran had sent four people from his village to Riyadh, Medina, and Jeddah, two of them to work for the same sheikh for whom he had worked.

More from The Big Roundtable: The hotel of enlightenment

Habib, meanwhile, was making only enough money to feed his family, the equivalent of perhaps $100 a month — a fifth of what he said Imram told him he could make in Saudi Arabia. Habib had studied till the fifth grade at a municipal school in Kundarki. He could read with some difficulty and could sign his name in Hindi. "I wanted change," Habib would later say. "I wanted to do something else with my life. Give my family better things."

In May 2009, Imran began visiting his relatives in nearby villages. His sister spoke with Habib's sister, who, in turn, spoke with Habib's wife, Humsari, about his going to Saudi Arabia. But the trip would come at a cost and no one was willing to lend Habib the money.

But then there was the land.

The family was divided about selling it. Habib's older elder brother, Jalaluddin Hussain, who lived next door and who tilled the adjoining parcel of land, opposed the idea. But Habib was determined. He told Jalaluddin that because Imran was a relative, nothing could go wrong. Habib prevailed. He sold the goats, a buffalo, and the land. He used some of his money to host a feast for his family and friends in Kundarki.

Then, a week later, he left to seek his fortune.

He would return six months later, in circumstances far different than he, his wife or anyone in Kundarki could have imagined, escorted from detention to courtroom, again and again, as a judge in Jaipur tried to determine whether Habib was a threat to the nation's security or, as he claimed, a victim of what amounted to indentured servitude, servitude so humiliating that he sought his freedom by stowing away in the toilet of an Air India flight out of Medina.

More from The Big Roundtable: Blood, honor, partition

The big water tank at Kundarki stands over a wide swath of land that is the bulk vegetable market. At one corner of it, just before the main entry to the market, Kalway Ali sits in a chair by his furniture shop.

Kalway is in his early forties and sports a beard and prayer cap. We exchange pleasantries and he sends a boy in the shop to fetch special "ginger-cardamom" milk tea. The villagers, wrapped in shawls against the December winter morning, gape and smile at me. Kalway and I begin talking. Others often interrupt.

"Habib will be here tomorrow," he says. "He has gone to work and could not get a day off today."

I have come to Kundarki to meet Habib, to hear his telling of the events that led to his escape. First, I have a question for Kalway, who wants me to know that all of Kundarki was thrilled at Habib's return.

It's a matter of great honor to go to Saudi Arabia, I say. What do you make of how people are treated there?

Kalway gets animated. "Oh Lord! Not good. Not good at all. People go there thinking we will make money and send it home. Leave their wives and children behind. Get our boys and girls a little more educated. Go for Haj. However, nothing of the sort happens in Saudiya," he mutters. Saudiya is the local slang for Saudi Arabia.

The next morning I return to Kalway Ali's furniture shop. There are more villagers there than yesterday. It's nippier than the day before, too, and the village folk are tightly covered in shawls and caps. Tea is ordered again. Soon comes a ripple of cheers from the people gathered. A young man zips into the storefront on his bicycle. A boy calls me. As I proceed toward him, the man gets off the bicycle and greets me with a tight handshake. It is Habib Hussain.

He is slim and his thick black hair is oiled and neatly combed. Habib still has the stubble that I saw in the photograph that ran in The Hindu. But he looks fresh and energized. He seems far removed from his past. The eyes that looked so lifeless in the photo now look well rested.

We begin to talk and 10 or so villagers seem eager to chime in. Habib and I move into a space where logs of wood are stacked.

The first thing Habib talks about is greed. "I got greedy," he says "I was blind. And I paid the price for it. I should have been more smart while getting into all this."

I ask what Imran, the agent, told him. Habib is convinced that Imran — whom he believed he could trust because they were relatives — deceived him. Still, "Please do be careful when you write about him," Habib says. "It's a question of my sister's life."

Imran, he says, "promised I would find a job in a company or an office." Yes, he concedes, the Saudi visa that Imran arranged for him clearly stated he would do the job of a cleaner. (All Saudi Arabian work visas specify the category of worker.) "Yes, it was a cleaner's visa and I had made it clear to Imran that I wanted to work in an office. He said with the same visa I could do other jobs. The cleaner's visa was for just the purpose of first getting to Saudi Arabia."

Imran got Habib's passport issued in June 2009. The total expense — including Imran's charges, the visa, and immigration fees, and the air ticket — amounted to 110,000 rupees, or $2,227. Habib had been earning 5,000 rupees from produce he sold off the land. The money he spent to leave for Saudi Arabia was almost two years' of what had been his income.

When the journey began, Habib spent a week in Mumbai, at an accommodation that Imran arranged, a dingy room in a lodge in a predominantly Muslim neighborhood, a small room he shared with two other people. Over the next few days, Habib underwent blood and urine tests at a hospital that issued reports recognized by Saudi Arabian authorities. Habib had expected Imran to hold his hand from the moment he left Kundarki till the time he reached Saudi Arabia, but he was on his own. "He could at least call me and speak to me and stay in touch," Habib says. "He hardly kept in touch."

Habib tells me about the day of the visa interview at the Saudi Embassy in Mumbai. "I wanted last-minute instructions from Imran and we spoke after many days," he says. "He told me what will be asked and what to answer. But he had also promised to buy me good clothes and I didn't have any good ones."

As he waited in line for his visa interview, Habib says, an officer looked at him, pointed to the slippers that he was wearing, and moved him into another line. Habib believes that the first line he was in was for those applying for a slightly "superior" visa, one for a plumber or electrician or factory worker. But in Habib's telling, the officer looked at his appearance, muttered something in Arabic, and moved him to the section handing out work visas for "cleaners." Habib got the visa eventually, but was furious with Imran. "I called him that evening, but he kept saying it would not be an issue," Habib says. "Deep down, though, I knew it was a problem."

Habib doesn't remember the exact day he flew from Mumbai to Jeddah, but the month was July, in 2009. His first flight ever, and an international one at that, was on Air Arabia. Habib was excited about Saudi Arabia. But, he says, when he landed at King Abdulaziz International Airport, there was no one to pick him up or to give him directions. "I waited for two-and- a-half hours at the airport, looking here and there," he says. "I did not expect this." Habib had a few hundred Saudi riyals. He tried calling Imran but the call wouldn't go through. He did not want to call his family, though the thought often crossed his mind.

After two hours of waiting in the lobby of the airport with his luggage, a man turned up. He was an Arab wearing a traditional dishdasha. He looked at Habib, called his name, and checked his passport and visa. He asked Habib to come with him. For almost half an hour, Habib tells me, he followed this man, pushingwith his baggage trolley, until they reached a series of rooms in the airport. This man instructed Habib to stay inside till he returned. He told Habib he would be back in half an hour. When he left, Habib heard the door snap. The room had been locked from the outside.

READ THE REST OF THIS STORY AT THE BIG ROUNDTABLE

This story originally appeared at The Big Roundtable. Writers at The Big Roundtable depend on your generosity. All donations, minus a 10 percent commission to The Big Roundtable and PayPal's nominal fee, go to the author. Please donate.

-

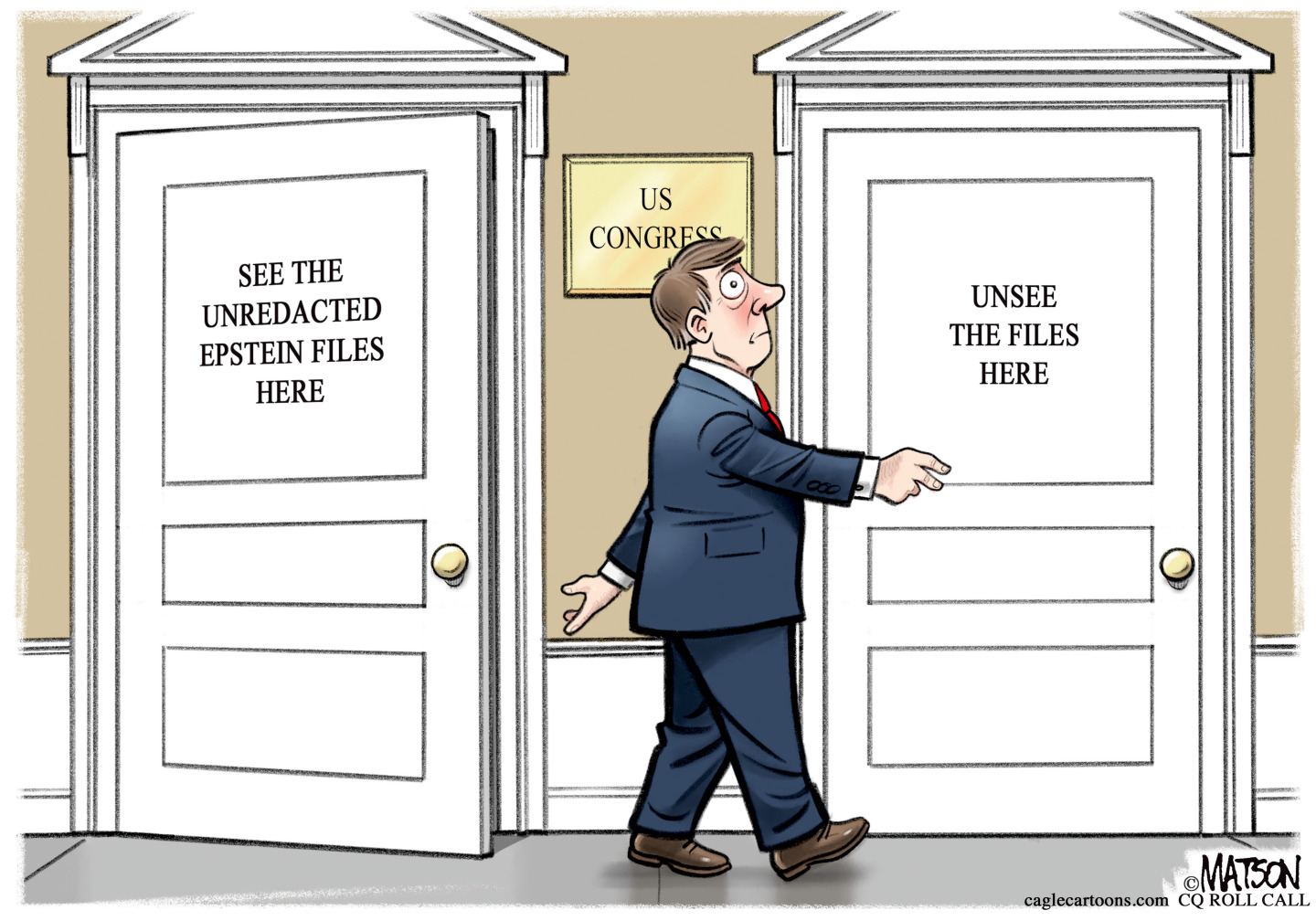

Political cartoons for February 11

Political cartoons for February 11Cartoons Wednesday's political cartoons include erasing Epstein, the national debt, and disease on demand

-

The Week contest: Lubricant larceny

The Week contest: Lubricant larcenyPuzzles and Quizzes

-

Can the UK take any more rain?

Can the UK take any more rain?Today’s Big Question An Atlantic jet stream is ‘stuck’ over British skies, leading to ‘biblical’ downpours and more than 40 consecutive days of rain in some areas