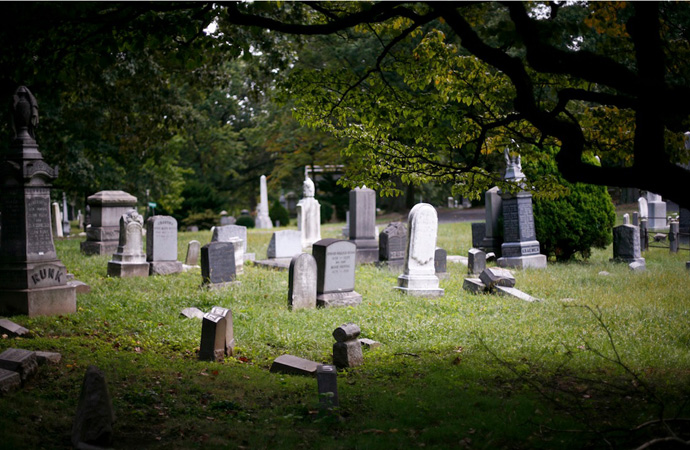

How I decided where to be buried

Exploring the convoluted and costly business of where to spend an afterlife in New York City

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

If you want to make someone immediately uncomfortable, ask what he plans to do with his body when his heart has stopped beating and his flesh has gone cold.

Recently, I received an envelope from the Pinelawn Memorial Park and Garden Mausoleum in Farmingdale, New York. Inside was a free booklet titled, "Let's Face It Now" and a letter that explained how taking charge of your death — though the word "death" was never mentioned — offers a sense of accomplishment and peace of mind. I'm 31 years old. Other than mild asthma and the occasional cold, I am healthy. So I was unnerved and even offended that Pinelawn had targeted me as a potential customer.

But maybe the Pinelawn folks had chosen the right person after all. As an incurable procrastinator, one of the things that frightens me most about death is that I won't be prepared. Death is not accommodating. Don't I get one phone call? A final meal? One more paragraph in the novel I'm reading? I may never know how it ends.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

What's worse, I might not have achieved my legacy yet — a house with a backyard, grandchildren, a Pulitzer. And as the letter from Pinelawn reminded me, living in a city of eight million people, on the moment of my passing there just might not be room for me. With so many other variables out of my control, I decided it was time I found a place to rest when I'm dead. Feeling very adult — 31 is not that young — as well as a touch morbid, I took the train to Green-Wood Cemetery in Brooklyn, in search of a place to begin my afterlife.

(More from Narratively: The forgotten streams of New York)

As the name Green-Wood suggests, the cemetery boasts lush grasses and hundred-year-old trees. Rustic signs indicating different paths — Blossom, Berry, and Birch — curl around so many hills. On the Sunday after St. Patrick's Day, I joined the "Eminent Irish Tour." Green-Wood offers tours most Sunday afternoons and every Wednesday. At one stop, Ruth Edebohls, our tour guide, shared the story of a scrappy Irish immigrant who went from rags to riches, and at another she spoke of a courtesan, Lola Montez, who was famous for her seductive Spanish spider dance. Her admirers included Andre Dumas, Victor Hugo, and Honoré de Balzac.

As we stepped sideways up certain inclines, Edebohls, who has been giving tours for the last 15 years, explained that her "clomping" was due to two hip replacements and a knee replacement. Clearly, these two hours were a labor of love.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

While I listened to her stories of the dead, I was also looking at the newer graves, taking notes on location, and searching for open space. I was looking for my place to rest.

* * *

America's first pioneers kept burial simple — people were interred where they died. Friends of the deceased were unlikely to return to the spot and didn't want to draw any strangers' attention to it, so they left the grave unmarked. In time, people began marking the burial spot with wooden slabs carved with the initials of the deceased. In the 1700s, as frontier homes transformed into farming estates, isolated graves became clusters of graves, which were shared with neighbors. Then, for some families, churchyards replaced farm burial. As villages grew into bustling cities, church graveyards became more crowded, and less pleasant to visit; both factors led to the development of today's rural cemeteries.

Green-Wood Cemetery was founded in 1838, predating both Central and Prospect Parks. It was built upon the terminal moraine — the rocky debris deposited by glaciers that stretches from Staten Island through Brooklyn and Queens. Rural cemeteries, like Green-Wood at the time, served not only as burial grounds but as garden retreats, following the model of Mount Auburn Cemetery in Massachusetts and Père Lachaise in Paris. In addition to the wealthy deceased residents, its gentle hills, glacial ponds, and stunning view of New York Harbor drew strollers, picnickers, and in the 1850s attracted as many as half a million tourists a year. Charles Dickens and the King of Hawaii were among them. As a U.S. travel destination in the 19th century, it was perhaps second only to Niagara Falls, says Jeff Richman, who authored a book about the culture and history of Green-Wood.

Easily one of the finest cemeteries in New York, securing a spot there in advance could cost between $12,000 and $22,000 today. In recent years, the cemetery has reclaimed old paths and a handful of ponds to create more space for graves; however, in ten years, there might not be any lots left to sell.

(More from Narratively: The master of a dying art)

Edebohls, who has honey blonde hair, favors movie star make-up, and has a love for anything Victorian, is comfortable talking about death, even her own. "It's just a matter of temperament," she told me when we met a few weeks after her tour. She believes the dead watch over us. A medium once told Edebohls she could see spirits in the trees along every stretch of her walking tour. Edebohls was delighted.

On a pleasant Tuesday morning, she and I stopped at an open patch of grass, on a hill, backed by a copse of firs. This was the spot Edebohls has chosen for herself and her ex-husband. "It's hard for a lot of people to understand why I'm so happy to have my burial spot," she said. But she and her ex-husband are both glad to have that part of their future, or fate, settled. While they aren't romantically involved, Edebohls said they've reconnected "spiritually" and now speak everyday.

A single grave generally holds two to three people. Coffins are stacked one on top of another with two to three feet of dirt in between. Edebohls, whose ex-husband is ten years older, expects she will be on top, but "you never know," she said.

Edebohls' pink cheeks sparkled beneath her sunglasses as she spoke about her future neighbor, an Irish woman. "She died in 2007. She gets lots of visitors," she said, seeming oddly pleased.

Like Edebohls, my mother, an Irish-born Roman Catholic, is unfazed by death — her own or anyone else's. When she first began her job as a hospice nurse, I was nine. It made me think of death all the time. I spent weeks staring at the ceiling, afraid that I might fall asleep and not wake up. At night, I listed the names of those who had died: my babysitter; my grandfathers, and two teenage boys from my town, Yardley Pennsylvania. The list grew. Whether I was praying or deliberately giving myself nightmares I still don't know.

Reminders of my mother's former patients were everywhere in our home: A photographer left her a framed picture of the ocean; a woman we called Granny had gifted her a nativity scene entirely made of corn husks; a collector of rare books had given me a favorite novel. These keepsakes haunted me. It wasn't until I was older, until I had lost friends myself, that I realized how special it was to have that one item — a T-shirt, a mix tape, a photograph — to remember them by.

* * *

I returned to Green-Wood several times, allowing myself to get lost inside, dwarfed and distracted by the elegant statues and the bedroom-sized mausoleums. I looked at the graves, read the epitaphs, slid cards to one side so I could better see a photograph. People left more than flowers. They left bracelets, pinwheels, balloons, prayer flags, paperweights, teddy bears, Barbie dolls, and tiny bottles of liquor. In front of one headstone — engraved with an image of a young man in a backwards baseball cap — sat a giant birthday cake made of artificial flowers. The banner read "Happy Birthday in Heaven" and the card "love your heartbroken mother." As strange as I felt and as troubled as I might have looked to anyone who saw me, I was encouraged by something Edebohls had said about the dead appreciating their visitors. I counted the stones left by others — a Jewish tradition that has been adopted by other faiths — and sat in the chapel.

From the outside, the chapel in Green-Wood is an exquisite triple-domed terra cotta masterpiece. While it was designed by the same firm that built Grand Central, Warren and Wetmore, the chapel is more understated, more delicate, as if the building itself understood the need for restraint. Still, I envision a couple taking wedding photos on the front steps and I'm not wrong. The space is also available for weddings, book talks and gallery exhibits. Once emptied of people, it lends itself to quiet reflection.

I left through the main gates, passing under striking domes, Gothic spires, flying buttresses and a scene of Jesus and his apostles carved from stone. On the grey day I first visited, these gates were ominous, begging for a clash of thunder and spooky disembodied laughter. Gut on a bright spring day the scene is stunning, in just the opposite way — filled with bird song and squirrels, flowering gardens and towering oaks. I wished for more time there.

(More from Narratively: You've never seen an antique eyeglasses collection this massive)

A few weeks later, I walk through a more modest entrance at The Cemetery of the Evergreens, which straddles Bushwick, Brooklyn, and Ridgewood, Queens. This time, I'm not alone.

"It's Cemetery of the Evergreens. That is its legal name, not The Evergreens Cemetery," Allan Smith, a former architect and local historian, tells me for the third time. Smith has written a book about one cemetery and helped restore another. I ignore both the brochure and the website, because the name matters to Smith and because it really does sound nicer. Smith, now in his early seventies, has been visiting this cemetery since the late 1940s. He carries a green bookbag and wears a sullen expression like a scolded eight-year-old boy. He's not the type to force a smile to ease the strain of a conversation, but he isn't unfriendly. And when he talks about cemeteries, he gets excited.

In the early 1800s, Smith explains, New York experienced a burial crisis. The population had nearly tripled and in addition to overcrowding, people worried about the spread of diseases such as smallpox. The water table was rising, or at least residents believed it was.

"They thought corpses were mixing with the water," Smith says. Internments were banned in lower Manhattan, and in 1847 the Rural Cemetery Act was passed. This allowed investors to build commercial cemeteries in the boroughs beyond Manhattan. The Cemetery of the Evergreens was built two years later.

This talk of corpses mixing with water reminded me of the Sundays I spent as an altar server in our small-town church in Pennsylvania, braiding the tassels on my robe, and staring at a bronze plaque that hung between two stained glass windows and paid the following tribute: "Gwendolyn, daughter of Charles and Mary Spong, who died at sea April 27, 1903. Age nine months."

I wondered whether Gwendolyn was buried under the church, or in the yard? Or if her parents had been pressured by other passengers to leave her body at sea. I pictured a swaddled Gwen, released from her mother's hands, falling through strata of water, growing darker and colder. Batted about by sharks and dolphins, Gwen becomes an offering for the starfish, sea anemones and eyeless creatures who don't even realize how dark it is on the ocean floor. At this point, a lay reader would nudge me and point with his chin to the cushions that needed to be laid at the altar gate or at the ushers waiting for communion plates. My daydream was over.

Read the rest of this story at Narratively.

Narratively is an online magazine devoted to original, in-depth and untold stories. Each week, Narratively explores a different theme and publishes just one story a day. It was one of TIME's 50 Best Websites of 2013.

-

The mystery of flight MH370

The mystery of flight MH370The Explainer In 2014, the passenger plane vanished without trace. Twelve years on, a new operation is under way to find the wreckage of the doomed airliner

-

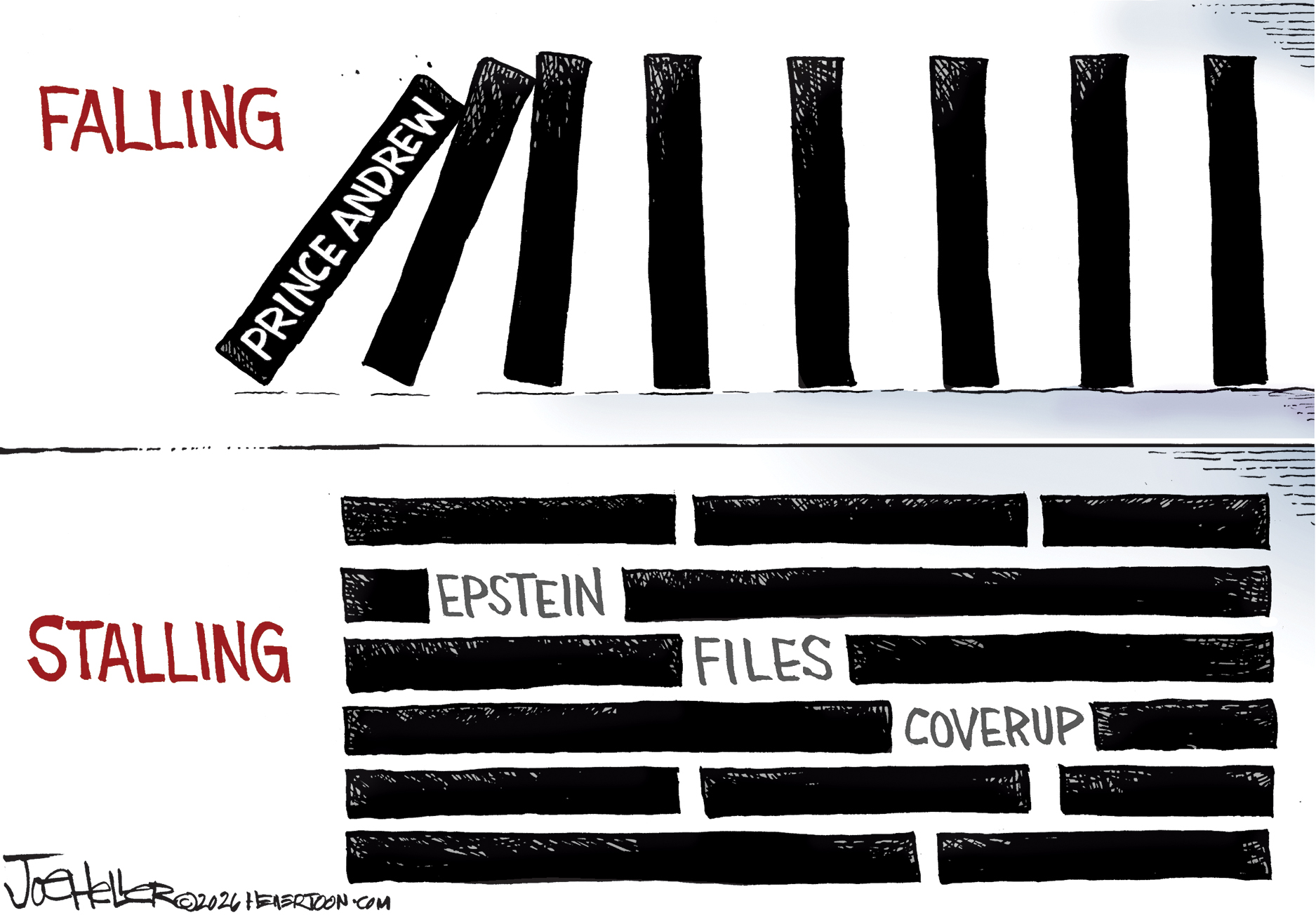

5 royally funny cartoons about the former prince Andrew’s arrest

5 royally funny cartoons about the former prince Andrew’s arrestCartoons Artists take on falling from grace, kingly manners, and more

-

The identical twins derailing a French murder trial

The identical twins derailing a French murder trialUnder The Radar Police are unable to tell which suspect’s DNA is on the weapon