The voices in my brother's head

After schizophrenia upended a young man's life, the notes he left behind offer clues to the horrors that haunted his mind

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

We missed the early signs.

I can't put a date on the first time we suspected a problem. I was in my early teens and Fred was probably about 17, so just about 40 years ago. Fred was a normal kid, an awesome athlete who excelled at every sport he played, but around his senior year he seemed to be angry all the time and would come and go at home as he pleased. We suspected drugs. When someone you know and love begins to slowly change before your eyes, no one thinks, "Hmmm, he must be mentally ill." You think drugs, you think alcohol, you think of any excuse but mental illness.

Unless you have witnessed schizophrenia firsthand, you can't possibly imagine the fear, the frustration, the anger, the sadness, and most of all, you can't begin to understand the hopelessness you feel for your loved one. It's an ugly fight, and the reality is that few ever win the battle. Schizophrenia will eat you alive and it takes your entire family with it. The lucky ones will manage to function in this world, but they still don't fit here.

Article continues belowThe Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

(More from Narratively: Capturing the briefest of lives)

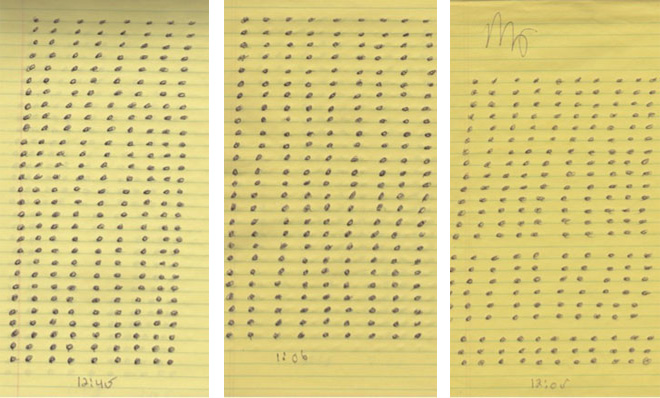

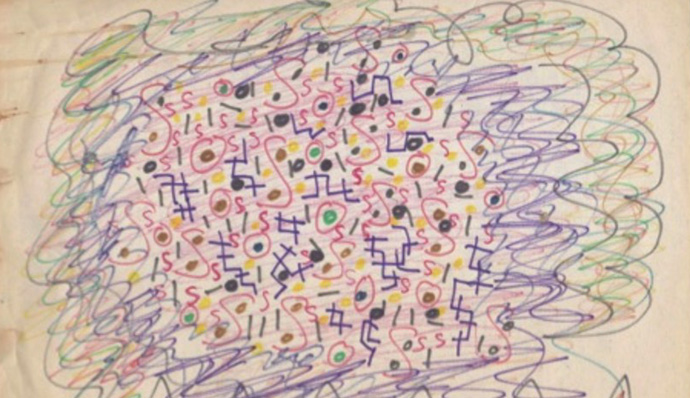

After Fred died, I was cleaning out a few drawers in his room and came across legal pads he had filled with notes and drawings. As I read the writings and saw page after page filled with row upon row of dots, it became clear to me just how tortured his mind must have been. I began to wonder if he ever had a moment of peace.

I decided to share these so that others might understand how fragile a mind can be.

One of my earliest memories of Fred's illness is of him running down the stairs and telling my parents that God told him to collect $20,000 or he would have to burn the house down.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

I was confused and petrified. When I looked into his eyes, I got scared because what I saw wasn't Fred. Even at my young age, I knew that Fred was not in there at that moment.

Shortly after the first incident, he attempted to throw a piece of furniture through his bedroom window. My parents had no choice but to call the police and request that Fred be brought to a hospital. At the police station, the dispatcher, in front of my parents, got on the radio and requested an ambulance to pick up "some wacko" and get him to the hospital. I can't begin to imagine my father's anger and hurt at hearing the dispatcher refer to his son as "some wacko."

From that moment, Fred became part of a system that really had no clue how to deal with him. I am not faulting anyone; it is simply a fact. The 1970s and '80s were hard on the mentally ill, and in many ways, things haven't changed much. Fred was repeatedly put in the hospital for short stints and either drugged for 24 hours a day or just released after a day or two, as if his mental illness would go away like the flu.

As his behavior worsened, he would disappear for days at a time. He sometimes came home and threatened us. He became increasingly paranoid and would accuse us of controlling his thoughts and mind. It is important to note that he never once hurt any of us, although we didn't know if he would, and believed he was very capable of doing so.

(More from Narratively: Tales from talking to strangers)

I went from feeling sorry for him to trying to block him out of my life. I am ashamed to say that I avoided him at all costs and fought with my parents because I felt that they should just throw him out. He disrupted my childhood, he disrupted my time with my parents, he disrupted my life, and I wanted it to end.

Coming home from school one day, I opened the door and found Fred sitting on the steps with a family photo album. He had a red marker in his hands and was placing an "x" on the faces of my parents. I will never forget the fear I felt when he looked up at me and said, "I'll give you ten seconds to get out of the house."

I backtracked out of the door and waited in my car for my parents to come back.

The hardest part of this illness is that it is so unpredictable. One day Fred would be fine, the next he would be agitated and sullen. When Fred was worried about something, he would pace all day and all night. He would pace in the house and he would pace outside. He wouldn't eat and he would smoke like a chimney and drink coffee nonstop.

Eventually, he was committed to Greystone Park Psychiatric Hospital for a while. More than once, Fred managed to walk away and show up at our home. We would let him in and call my father at work, who would come home and try to talk Fred into going back. Meanwhile, we sat in fear and prayed he wouldn't do anything.

Read the rest of this story at Narratively.

(More from Narratively: The dame of dictionaries)

Narratively is an online magazine devoted to original, in-depth and untold stories. Each week, Narratively explores a different theme and publishes just one story a day. It was one of TIME's 50 Best Websites of 2013.