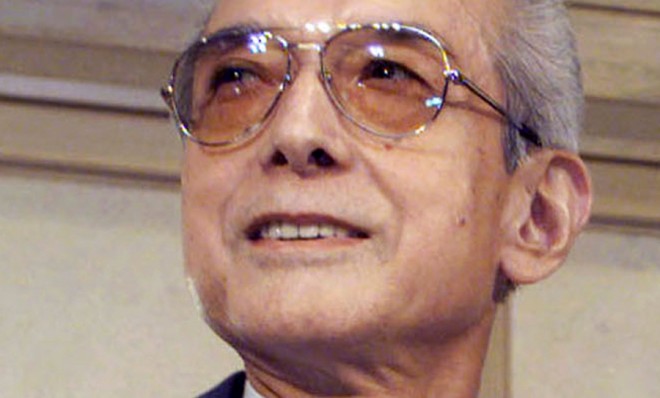

How Nintendo legend Hiroshi Yamauchi changed video games forever

The man who gave the world Mario and Donkey Kong has died at age 85

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

In 1949, Nintendo was a small company in Tokyo that made playing cards. Today, it is the biggest video game company in the world in terms of revenue.

The man responsible for that shift, former company President Hiroshi Yamauchi, died on Thursday of pneumonia at a hospital in central Japan. He was 85.

Nintendo fans reacted on Twitter:

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Yamauchi took over Nintendo — which had been making playing cards since 1889 — when his grandfather died in 1949. In the following years, Nintendo expanded into several other areas: Noodles, toy blocks, a taxi service, and even a "love hotel."

It was in 1977 that he finally ventured into the nascent video game industry. His best decision might have been hiring game designer Shigeru Miyamoto, the man responsible for creating characters such as Donkey Kong, Mario, and Zelda.

Three years later, Nintendo released Game & Watch, the first-ever portable gaming system. Then came:

- Nintendo Entertainment System, 1985 (released as Famicom in Japan in 1983)

- Game Boy, 1989

- Super Nintendo Entertainment System, 1991 (released as Super Famicom in Japan in 1990)

- Nintendo 64, 1996

- GameCube, 2001

He finally stepped down as president in 2002. By then, he was one of the richest men in Japan, and also owner of the Seattle Mariners (which he sold in 2004).

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

His biggest accomplishment, though, was making the Nintendo Entertainment System (NES) a hit.

He entered the market after the "great video game crash of 1983," a time when stores were flooded with cheap Atari wannabes. It didn't help that any third party could make and sell Atari games, which, predictably, resulted in a lot of terrible video games.

Nintendo, like Apple, didn't invent a new market. Instead it improved on what already existed and imbued its own products with a sense of craftsmanship.

"After the video-gaming crash of 1983, consumer confidence in video-gaming was practically non-existent," writes PixelVolt's Kevin Rhine. Instead of letting third parties churn out titles, Yamauchi "sought to build consumer confidence by touting the quality of his games," says Rhine, coming up with the "golden 'Official Nintendo Seal of Quality' stickers placed on cartridges to ensure their validity."

As The Verge's Aaron Souppouris put it, "The NES was a huge risk for Nintendo" but was eventually credited "as the catalyst for the rebirth of the video game industry."

Part of the reason Nintendo succeeded, IGN's Lucas M. Thomas wrote in a tribute last year, was that Yamauchi was a "stubborn, hard-headed man" who, like Steve Jobs, demanded a lot from his employees:

Nearly every decision Hiroshi made from the dawn of the '80s until his retirement 10 years ago was absolutely critical in bringing Nintendo to the market-leading position it's enjoyed through these past three decades… If ever there's been one in the video game industry, Hiroshi Yamauchi was...a man of extremes. A man whose own satisfaction always seemed to be just beyond reach, even as he led a company who made joy a little easier to grasp for millions of others. [IGN]

To jump into a market when everybody else was jumping out took courage and foresight, argues Ian Livingstone, former chairman of publisher Eidos.

"He understood the social value of play, and economic potential of electronic gaming," he tells the BBC. "Most importantly he steered Nintendo on its own course and was unconcerned by the actions of his competitors. He was a true visionary."

Yamauchi is also the reason why you will be humming this song for the rest of the day:

Keith Wagstaff is a staff writer at TheWeek.com covering politics and current events. He has previously written for such publications as TIME, Details, VICE, and the Village Voice.