3 reasons why U.S. manufacturing is on the rise

Suddenly, outsourcing the assembly of products to China doesn't make a whole lot of sense

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

August was a good month for factories. The U.S. manufacturing sector grew at a faster rate over the last month than at any other time during the last two years.

Not that the U.S. economy has made up the millions of manufacturing jobs it hemorrhaged over the last two decades. Back in the early 1990s, 17 million Americans worked in manufacturing. Today, that number is more like 12 million.

Still, factories reported to financial firm Markit "that demand often exceeded production" last month, which, the firm's chief economist Chris Williams told Reuters, means "factories will need to ramp up production to replace depleted inventories."

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

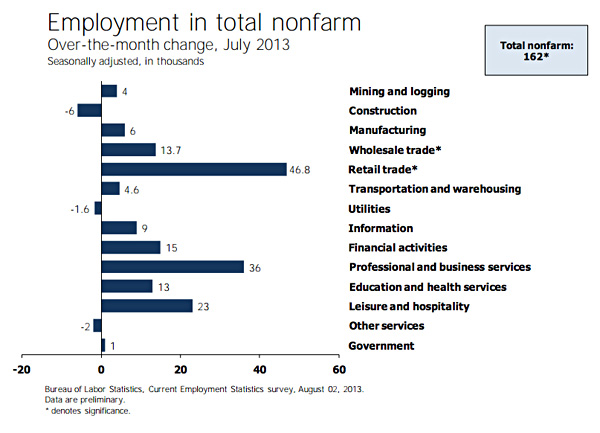

Data from July shows that the manufacturing sector, despite trailing retail and other service industries, is still one of the areas of the U.S. economy that is adding jobs:

And the overall boost in manufacturing over the last two months has some economists hopeful that the country is headed for recovery. What is responsible for this increase? Three reasons:

1. Global demand is on the rise

The Great Recession decimated demand for American-made products. Now, as the global economy picks up, so is demand for the sort of products America has long exported to the world.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

This isn't limited to goods made in the United States. Manufacturing is up in the U.K. and China, too. Spain and Italy saw manufacturing activity grow for the first time since 2011. Ultimately, The Guardian's Phillip Inman writes, the manufacturing output numbers "gave the strongest indication yet that the richest countries are finally shaking off the after-effects of the financial crisis."

2. China isn't as cheap as it used to be

Wages in China have jumped so much that Chinese business owners are actually hiring undocumented workers from Myanmar and Vietnam to work in their factories. That, in turn, has made it only marginally cheaper for U.S. businesses to manufacture goods in China.

When you factor in both labor and energy costs, it costs only 5 percent more to build something in the United States than to have something shipped from Chinese industrial centers like Chengdu or Shenzhen. That has led to companies like Apple, which experienced a PR nightmare following a string of suicides at the Foxconn facilities in China, to move some of its manufacturing back to the United States — in this case, its new line of Macs are made in factories in Texas.

Keeping factories near distribution networks also gives companies the added advantage of being able to get products to customers more quickly, which is why Motorola is making its Moto X phones — which need to be built custom after being purchased — in Texas as well.

3. Relatively affordable U.S. labor is attracting foreign companies

The factory jobs of today don't look like they did in the past. Many of them are part-time, non-union jobs that require specialized technical skills. The low cost of labor is actually making it more cost-effective for some European and Japanese companies to manufacture products in the United States, most notably Ikea, which just opened a factory in Danville, Va., and France's Airbus, which is opening a factory in Alabama.

There are also fewer legal barriers to shutting down factories in the United States than there are in Europe. Tim Fernholz of Quartz quotes a report by the Boston Consulting Group that shows how costly it can be to fire factory workers in Europe:

German law mandates that workers may remain on the job, at full pay, for anywhere from a few months to more than a year, depending on how long they have been employed by the company, while layoff terms are being negotiated and after notification of a layoff has been received. [Quartz]

More lax U.S. labor laws, as Fernholz notes, "may make the United States an attractive spot for multinationals, but economies that live by cheap labor costs can die by them, too."

Keith Wagstaff is a staff writer at TheWeek.com covering politics and current events. He has previously written for such publications as TIME, Details, VICE, and the Village Voice.