Martin Luther King Jr.'s dream was also about jobs

Racial equality remains notably lacking when it comes to economic issues

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

As people gather in Washington, D.C., to commemorate the 50th anniversary of Rev. Martin Luther King Jr.'s "I Have a Dream" speech, much of the focus will be on how much progress America has made towards racial equality.

One area where there is a lot of room for improvement: Jobs, a topic King was familiar with.

"Although the 'I have a dream' and the 'content of their character' bits tend to get top billing in these remembrances, the event was called 'The March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom' — and it's worth noting that the word 'jobs' comes before 'freedom,'" wrote Gene Demby of NPR's Code Switch.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

America hasn't exactly lived up to King's dream, many in the black community say.

"The most obvious failure to achieve equality is in the economic realm," Rep. John Conyers Jr. (D-Mich.), the only member of Congress ever endorsed by King, wrote in Politico. "Dr. King understood that civil rights included economic rights and that we can never truly form a more perfect union until income, wealth and opportunity are made more equal."

In many respects, black Americans are doing much better economically than they were in King's time. The problem is that they are still lagging behind other groups.

In 1966, the closest year to King's speech for which data is available, the poverty rate for blacks in the United States was 41.8 percent, according to the U.S. Census Bureau. Today, it's 27.6 percent — better than in the 1960s, but much higher than the national poverty rate for all races, which is 15 percent.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

In 1966, the median family income for black Americans was $22,266, adjusted for inflation. Now the median black family makes $40,495. Again, that is an improvement, but it's still only 66 percent of the median family income for all American families.

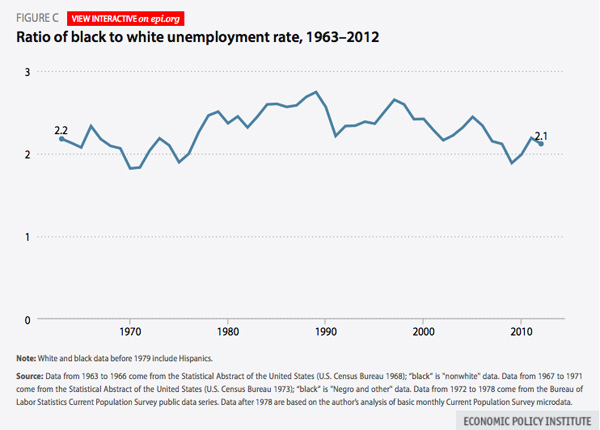

A report released earlier this summer from the Economic Policy Institute shows a similar picture of economic inequality. Consider that black Americans are still twice as likely as white Americans to be unemployed — exactly the same situation as 50 years ago.

In fact, the unemployment rate for black Americans is currently higher than the national rate of unemployment during the Great Depression. That statistic has dire consequences for black children, 45 percent of whom live in neighborhoods with concentrated poverty, compared to only 12 percent of white children.

The reasons why economic inequality persists among racial groups in the United States are, of course, both disputed and complicated.

As Demby noted, blacks were barred from many professions and colleges that helped a lot of white Americans move into the middle class in the 1960s. Furthermore, blacks were often denied home loans. "It's been a game of catch-up ever since," he said.

Not that black Americans don't face discrimination in today's economy. A recent study showed that the same resume with a white-sounding name was 50 percent more likely to get a response than one with a black-sounding name.

The black community has also been hit hard by the 2008 housing crisis, Algernon Austin, director of the EPI's Program on Race, Ethnicity and the Economy, told NPR, saying, "The more segregated a community, the more [likely there was] to be subprime lending in the community."

It's hard to deny that America has made progress since 1963. Still, as President Obama said last week,"The legacy of discrimination, slavery, Jim Crow, has meant that some of the institutional barriers for success for a lot of groups still exist."

Milton Ross, a 72-year-old retiree originally from Mississippi, shared a similar sentiment while talking to Bloomberg's Margaret Talev on the National Mall. "It's still two different worlds," he said. "I wish I knew the answer to why it's like that, but there's still two different worlds."

Keith Wagstaff is a staff writer at TheWeek.com covering politics and current events. He has previously written for such publications as TIME, Details, VICE, and the Village Voice.