Why most Americans hate their jobs (or are just 'checked out')

A new Gallup survey on the state of the U.S. workforce doesn't indicate a lot of happy desk campers

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

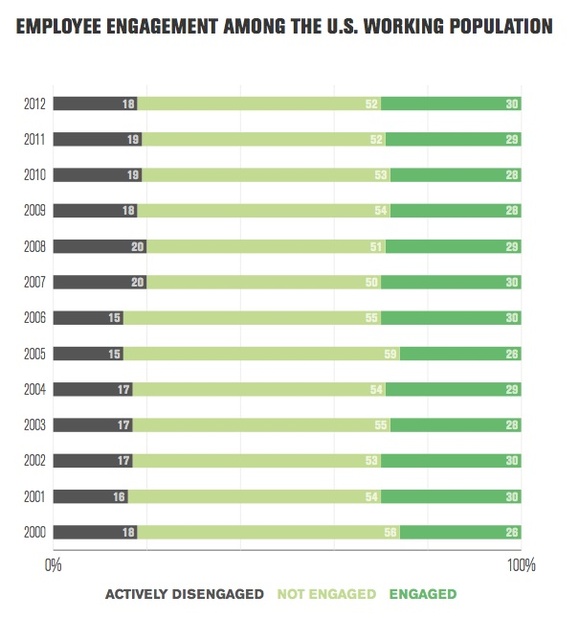

On average, some 100 million Americans were employed full-time in 2010-2012 — and 70 million of them either hated their jobs or were simply "checked out," according to a recent Gallup survey of America's workforce. (Read the entire report [PDF].) This trend actually isn't all that new: The 30 percent of employees "engaged" at work is at its high-water mark since 2000. But this prolonged disenchantment with our work doesn't make it less worrisome.

Nor does the happiness of the 30 percent make the unhappiness of everyone else less costly to the U.S. Gallup puts the price tag of active disengagement at up to $550 billion in lost economic activity each year. And even if America's unsatisfied workers have fulfilling home and social lives, boredom at the job means long days for everybody. "People who aren't engaged spend much more time experiencing emotions like worry, stress, and pain," says Gretchen Gavett at the Harvard Business Review.

Companies are belatedly paying attention to this, says Gallup's Jim Harter. "The general consciousness about the importance of employee engagement seems to have increased in the past decade," says Harter, the company's chief scientist for workplace management and well-being. "But there is a gap between knowing about engagement and doing something about it in most American workplaces."

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

The question, then, is why are so many American workers unhappy or bored? First let's look at the numbers and demographics. In 2012, the most recent year in Gallup's poll, 30 percent of American workers were "engaged," 18 percent are "actively disengaged," and the majority — 52 percent — are "not engaged." What does that mean? Gallup:

Engaged employees work with passion and feel a profound connection to their company. They drive innovation and move the organization forward.

Not Engaged employees are essentially "checked out." They're sleepwalking through their workday, putting time — but not energy or passion — into their work.

Actively Disengaged employees aren't just unhappy at work; they're busy acting out their unhappiness. Every day, these workers undermine what their engaged coworkers accomplish. [Gallup]

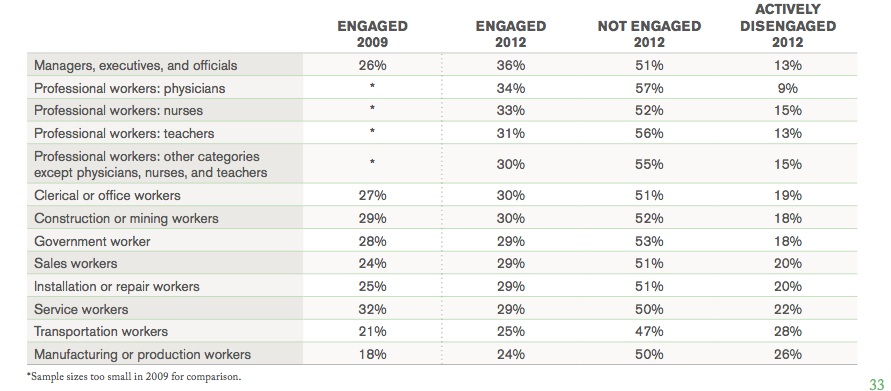

Women are slightly more engaged with their work — 33 percent versus 28 percent of men — as are managers and executives (36 percent) versus their underlings. Transportation workers are the least engaged, with 28 percent so unhappy they're out to undermine their company. Workers in Louisiana are the most engaged; Idahoans are the least.

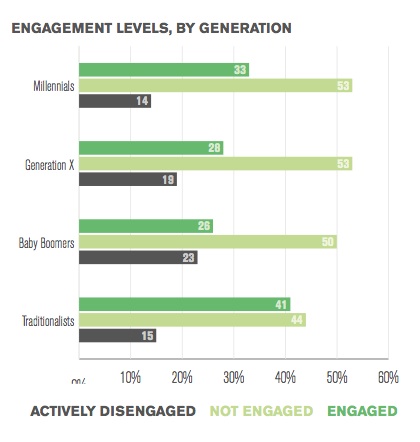

By age cohort, baby boomers (23 percent) and Generation Xers (19 percent) are the most likely to hate their jobs, while millennials are the least likely to hate their jobs (14 percent, though they have the highest boredom rate, at 53 percent). Unfortunately, boomers and Gen Xers each make up 44 percent of the workforce; millennials make up 8 percent.

All in all, the differences aren't that large and the bottom line is the same: America's workforce is generally bored or unhappy. A couple of key factors are the economy and health of the company. Active disengagement shot up to 20 percent in 2007 and 2008, during the brutal first leg of the Great Recession. And Gallup finds that employees of companies that are hiring are four times more satisfied than businesses laying people off.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Another factor may be that wages are stagnant or worse, while workload has shot up. A new study from the Urban Institute finds that 30-somethings today are worse off than 30-somethings in 1983, making them the only age group doing worse 30 years later — adjusted for inflation, their net worth is 21 percent less than in 1983. That means if nothing changes, this generation "will be poorer than their parents," says Terrell Brown at CBS News. "It's the first time that's happened in America since the Great Depression."

Those factors certainly come into play, says Timothy Egan at The New York Times. Not only are wages flat or declining for most workers, but "the gulf between those at the very top and those who do all the heavy lifting has never been greater," and in this tight job market, too many companies "promote a view that everyone is replaceable." Yet "the main factor in workplace discontent is not wages, benefits or hours, but the boss."

Yes, this is the Gallup report's "most important point (and biggest 'duh' moment)," says Harvard Business Review's Gavett. "Supervisors who focus on an employee's strengths have more engaged employees than those who focus on weaknesses or neglect to focus on much of anything at all." Or, as Gallup CEO Jim Clifton puts it, "managers from hell are creating active disengagement costing the United States an estimated $450 billion to $550 billion annually."

Flex time is another boost to satisfaction: People who work remotely are happier and harder-working than those who only work in the office, and workers who spend 20 percent of the time off-site are the most satisfied. But the main lesson for companies is that while ping-pong tables, hammocks, and free lunch may make a small dent in worker satisfaction, the biggest obstacle is bad supervisors.

"Regular praise, opportunity for growth, and the occasional question from a higher-up of a lower-down about how to improve things would go a long way toward getting the checked-out to check back in," says Egan at The New York Times. But on a different level, this "sad survey is further proof of two truisms" of American life:

One, the timeless line from Thoreau that "the mass of men lead lives of quiet desperation." The other, less known, came from Homer Simpson by way of fatherly advice, after being asked about a labor dispute by his daughter Lisa. "If you don't like your job," he said, "you don't strike, you just go in there every day and do it really half-assed. That's the American way." [New York Times]

Peter has worked as a news and culture writer and editor at The Week since the site's launch in 2008. He covers politics, world affairs, religion and cultural currents. His journalism career began as a copy editor at a financial newswire and has included editorial positions at The New York Times Magazine, Facts on File, and Oregon State University.

-

The ‘ravenous’ demand for Cornish minerals

The ‘ravenous’ demand for Cornish mineralsUnder the Radar Growing need for critical minerals to power tech has intensified ‘appetite’ for lithium, which could be a ‘huge boon’ for local economy

-

Why are election experts taking Trump’s midterm threats seriously?

Why are election experts taking Trump’s midterm threats seriously?IN THE SPOTLIGHT As the president muses about polling place deployments and a centralized electoral system aimed at one-party control, lawmakers are taking this administration at its word

-

‘Restaurateurs have become millionaires’

‘Restaurateurs have become millionaires’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day