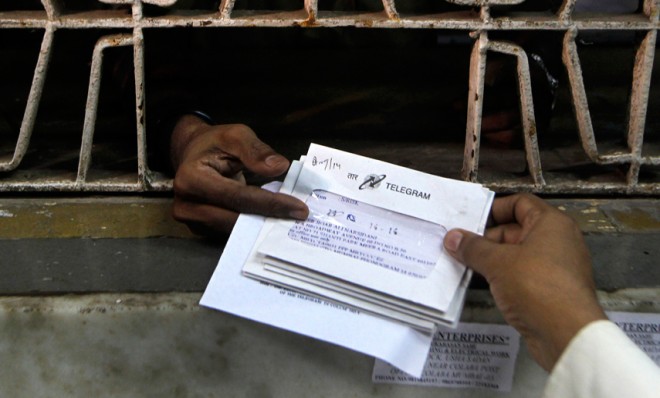

The last telegram ever is about to be sent

India is the last country with regular telegraph service. And the final message will be sent next month

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

On July 14, someone somewhere in India will tap out what is being called the world's last telegram. India's state-owned telecom company, Bharat Sanchar Nigam Limited, has been holding out as other countries around the world retire their antiquated telegraph services. Now, after delaying the move for two years, the business operating what is considered to be the world's last telegraph service is finally ready to pull the plug, saying telegrams are no longer commercially viable in the age of digital communications.

India's telegram service had been upgraded in recent years — clerks now type up messages on computers to be sent via telegraph, instead of using Morse code. But it still didn't work. "We were incurring losses of over $23 million a year because [text messaging] and smartphones have rendered this service redundant," Shamim Akhtar, general manager of BSNL's telegraph services, tells The Christian Science Monitor. There are still some private companies that offer telegram-style message message services. But the closing of India's state service is being called the end of the telegraph era.

Of course, few people are shocked that India is giving up on a technology that got its start nearly 170 years ago, when Samuel Morse sent the first telegraph message in Washington in 1844. "We're not sure if it's more surprising to learn that the last telegram in the world will be sent next month... or that people are still sending telegrams somewhere," says Ruth Brown at Newser.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Others are taking a different lesson from this telegram news. Matthew Yglesias notes at Slate that India lags far behind most countries in cell-phone use — just 26 percent of the population owned mobile phones last year. "All in all a valuable reminder," Yglesias says, "that alongside the thriving wired India you read about in Tom Friedman columns there's a vast and still overwhelmingly rural and low-tech country out there."

India's telegraph service is still sending about 5,000 messages a day, but the service — with just 75 offices and 998 employees — is a shadow of its former self. At its peak in 1985, the service was relaying 60 million telegrams a year from 45,000 offices, employing 12,500 people. In the U.S., Western Union shuttered its telegram service seven years ago.

The telegram still has its fans in India. Soldiers routinely use telegrams to exchange news with their families from remote outposts. And one frequent user, A.P. Tripathi — who runs an antic-orruption nonprofit — says the loss of the service will be a disaster for activists, as telegrams carry official weight in urgent situations. "For example," he said, "a telegram to a court informing them of illegal detention of a citizen by the police is taken as a writ petition." Tripathi even threatened to go on a Gandhian fast if the company doesn't reverse its decision to close the service.

It is true, notes Megan Garber at The Atlantic, that "a shrunken industry is not necessarily a dead industry." Telecom worker unions are pleading with Bharat Sanchar Nigam Limited to keep at least a skeleton service alive to preserve a form of communication that has been part of India's heritage since 1850. But, Garber says, BSNL is expressing no interest in keeping the service going as a living history exhibit.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

The telegram service is a business. And like most businesses, an end to profitability means, simply an end. Or in this case: a STOP. [The Atlantic]

Sometimes, media proclamations about the death of a tradition or a once-hot phenomenon are nothing but hyperbole. Will Oremus at Slate holds up recent reports of "the death of tech blogging" as an example. "We in the media kill things off so readily these days," Oremus says, "that it's easy to forget how long it actually takes a once-prevalent technology to vanish altogether."

The telegram should serve as a reminder: It often takes a really, really long time. Had there been a TechCrunch or a Forbes.com a century ago, some scribe would have no doubt declared the telegram defunct even then, done in by the rise of the landline telephone (itself the frequent subject of exaggerated death reports these days). In fact, though... it continues even now to play a role in the lives of some portion of the 74 percent of Indians who do not have mobile phones.Asked how he manages to make such accurate predictions in his books, the novelist William Gibson once explained, "The future is already here, it's just not very evenly distributed." The fact that telegraph service still exists in at least one corner of the Earth as of June... 2013, suggests a corollary to Gibson's axiom: The past is still here, it's just not evenly distributed. [Slate]

Harold Maass is a contributing editor at The Week. He has been writing for The Week since the 2001 debut of the U.S. print edition and served as editor of TheWeek.com when it launched in 2008. Harold started his career as a newspaper reporter in South Florida and Haiti. He has previously worked for a variety of news outlets, including The Miami Herald, ABC News and Fox News, and for several years wrote a daily roundup of financial news for The Week and Yahoo Finance.

-

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule works

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule worksIn the Spotlight The law is at the heart of the Colbert-CBS conflict

-

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?Today’s Big Question Democrats want to rein in ICE’s immigration crackdown

-

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day