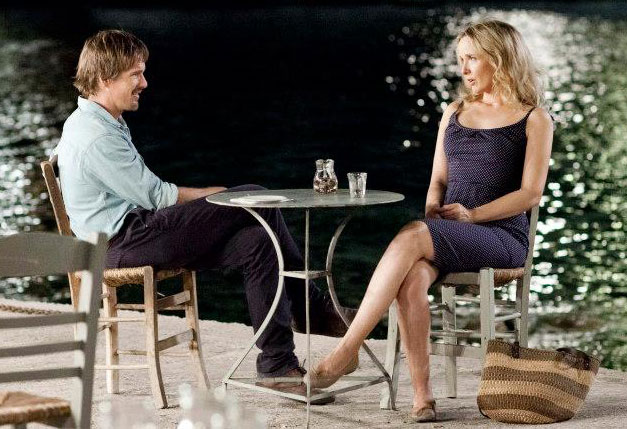

Girls on Film: Before Midnight and the evolution of one of cinema's most dynamic women

Over three films and nearly two decades, Celine is not only allowed to appear and intrigue us, but also to reappear and challenge us

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Richard Linklater, Julie Delpy, and Ethan Hawke's collaborative romantic trilogy — Before Sunrise, Before Sunset, and Before Midnight — contains some of cinema's most important films, but not for the reason you might think.

Yes, they are some of the most critically acclaimed cinematic romances in decades. Yes, they represent the "little engine that could" in a creative system in which only big-budget popcorn flicks tend to get multiple sequels. Yes, they are an enjoyable departure from the current standard of overly frenetic, quick-cut filmmaking. But they are also the only films that strive — and succeed — to create a detailed and ongoing look at the female experience.

Women are treated as enigmas in cinema. We're constantly learning what it means to be a man, from the wars of ancient worlds to the battles in the boardroom; we dig into the minutiae of superheroes, the particulars of space travel, and the motives of murderers. But women remain outside the realm of understanding. We wonder What Women Want, and need Gerard Butler to teach us The Ugly Truth.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

It's a near universal standard — with the exception of Julie Delpy's Celine.

We've seen less than three days of her entire life, but we know Celine because we have the rare opportunity to watch her grow over the 18 years separating the three films. We see her speak, think, and react — talking about everything from the joys of sex to the beauty of social work to the struggle of feminism. And we see how that changes as she grows from a woman in her twenties (Before Sunrise), to a woman in her thirties (Before Sunset), to a woman in her forties (Before Midnight). For all the series' romance — of which there is much, from the beautiful to the painful — the series thrives because it allows us to see one woman and one man evolve over the course of their lives.

Before Sunrise

Before Sunrise begins like many young romances do — two beautiful people meet in a romantic setting, throw caution to the wind, and explore their immediate attraction. Celine is the quintessential young intellectual of the '90s. She's a student at the Sorbonne, reading philosopher Georges Bataille while wearing a long skirt, white tee, long dress, and an excessively large flannel shirt. When she meets the cute, unkempt American Jesse, she has no interest in superficial conversation, immediately launching into an anecdote after he asks a question. This is a romance based on conversation — and for two people at the start of their adult lives, that means the intellectualism of their studies intermingled with the memories of their childhoods.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

In Before Sunrise, Celine is a romantic whose dreams were tempered by her practical parents, creating an edge that intermingles with her magnetic warmth. "God, everything pisses me off," she admits. But there's an undercurrent of hope and an embrace of all avenues of life. She's pleased with a traveling fortune teller's optimistic vision of her future, and though she rejects religion, she relates to the idea of followers coming together to look for answers to life's mysteries. "If there's any kind of magic in this world, it must be in the attempt of understanding someone, sharing something," she says.

One minute, she's floored by the poetry of a beggar, the next, she strives to bring romantic conversations back down to earth. She wonders what would be the first aspect of her personality that would drive Jesse mad, which is both a kind of entrapment and a fear that she's already being idealized into an expectation she could never live up to. In a conversational game in which Jesse plays a girlfriend she pretend-calls, Celine reveals: "I'm afraid he's scared of me… He must be thinking I'm this manipulative, mean woman. I just hope he doesn't feel that way about me, because you know me, I'm the most harmless person. The only person I could really hurt is myself."

Before Sunset

Jesse and Celine vowed to reunite in six months, but life kept them apart until Jesse wrote a book about their first encounter that ends up reuniting them. Their initial unease quickly dissipates as their chemistry leads to a banter befitting Nick and Nora Charles, but they are different people in a different story. Where Before Sunrise brought the pair together with thoughts and memories unrelated to each other, Before Sunset is a real-time conversation in which the revelations are inextricably linked to each other.

Celine is now a woman who has endured years of adult struggle. Many of her romantic ideas have faded away. She's still prone to ranting, but the rants aren't intermingled with romantic thoughts; her feelings are shackled beneath many layers of lies, pain, and experience. Instead of ideas about life and the future, Celine talks about experiences. She explains her work and her time as a student in New York, but is reluctant to talk about her music. She has evolved into her parents' practical application of her passions, with her curiosity and appreciation of life leading her to work for an environmental organization.

Celine reminisces about being a little girl so enamored with every little thing on her walk to school that she would always be late, adding, "Memory's a wonderful thing if you don't have to live in the past." Her neurosis is more visible. She gripes that Jesse idealized their first night together — something she surely would've done herself nine years earlier. She guards her memories, swearing that they didn't have sex in Before Sunrise to save her the pain of truly talking about the aftermath of their missed meeting. When religion comes up in conversation, she doesn't engage; instead, she immediately launches into an anecdote about oral sex. She swears she doesn't believe in ghosts, spirits, reincarnation (which she did in the first film), or God, but also fears being "one of those people who doesn't believe in any kind of magic."

But Before Sunset isn't as simple as a woman evolving and changing her point of view. Each step forward brings Celine one step closer to her inner, padlocked feelings. Her pain has made her guarded. At first she praises herself for no longer romanticizing things, that being alone is "better than being next to your lover and feeling lonely." Jesse's book reminded her how hopeful and "genuinely romantic" she was a decade earlier, how much of herself she lost. "Reality and love are almost contradictory for me," she reveals. Failing to reunite with Jesse in Vienna killed her romantic hope. Celine "detached," burying the romanticism behind lies about her memories of the night and her current life.

Seeing Jesse again forces Celine to come face-to-face with her idealistic youth. In Before Sunset, he still has much of the musing, romantic whimsy she has since lost, and every hopeful glance forces her to not only confront the emotional skeletons in her closet, but also reconcile who she was then with who she is now. Before Sunset sees Celine — in real time — face and decide whether she'll embrace her idealistic past or her sarcastic present. As much as Before Sunset is a story of rekindled love, it's also the story of a woman eager to be romantic again — but wary of the real-life implications.

Before Midnight

Before Midnight can't just echo its predecessors. As much as they evolve, Before Sunrise and Before Sunset detail a romance that lives only in assumptions from limited interaction. Jesse and Celine came together, fell for each other in a single evening of youthful lust, and got to live with those assumptions for nine years instead of doing the hard work of real life.

Celine feels like a different person in Before Midnight because the audience is finally allowed to see her outside of the intensity of her early couplings with Jesse and into her (almost) everyday life. Her neuroses and hotheadedness, obvious in the first two films, are no longer quirks but the actuality of day-to-day existence. She is even farther from her dreamy, young self. Celine is a mother of twins, partnered with a man-child who is still enamored with romantic ideas and has the space as a writer to explore them. She has become the "General," as she calls herself: Organizing, planning, and watching over, with, as she describes it, no room for spontaneity.

Jesse goes for long walks every day and thinks; Celine funnels her passion into the only outlet continually open to her: Conflict and fear. She is still the woman who buries the deepest pain deep within herself, and what doesn't fit turns into argumentative posturing. Jesse is now her antidote, expertly diffusing her anger and balancing her back into their witty banter, until her unrest becomes too large to handle with humor. Forty-something Celine is a woman struggling with life. She remembers her idealism; she's the feminist who wants an exciting life improving the world. But her life is no longer hers alone.

When Celine jokes about fearing the impact of spending time in the Grecian birthplace of tragedy, it speaks to the undercurrent of tension within her relationship, which comes to a boil before the film's end. When she romanticizes her memories of Roberto Rosselini's Journey to Italy, in which Ingrid Bergman faces a cemented couple of Pompeii, she reveals her desire to be firmly united with another — and also, the cracks she sees in her committed (but not married) relationship with Jesse.

Over 18 years, we have seen Celine as a young woman, a thriving professional, and a struggling but wonderful mother at her most idealistic and most vulnerable. We know her — and yet she is little more than a handful of moments gleaned from a handful of hours at the movies. Audiences idealize her, as Jesse did in Before Sunrise, but the sequels reveal what most films don’t care to share: The real life after the happy ending. We watch them fail to reunite, and struggle to stay together. We fill in the blanks of Celine's character with our own particular assumptions, but every nine years, we're given the best cinematic gift of all: A whole new arc that shows us where Celine has diverged from our own expectations. Celine is not only allowed to appear and intrigue us, but also to reappear and challenge us.

And this makes Celine one of the most — if not the most — dynamic female character film has ever seen.

Girls on Film is a weekly column focusing on women and cinema. It can be found at TheWeek.com every Friday morning. And be sure to follow the Girls on Film Twitter feed for additional femme-con.

Monika Bartyzel is a freelance writer and creator of Girls on Film, a weekly look at femme-centric film news and concerns, now appearing at TheWeek.com. Her work has been published on sites including The Atlantic, Movies.com, Moviefone, Collider, and the now-defunct Cinematical, where she was a lead writer and assignment editor.

-

Antonia Romeo and Whitehall’s women problem

Antonia Romeo and Whitehall’s women problemThe Explainer Before her appointment as cabinet secretary, commentators said hostile briefings and vetting concerns were evidence of ‘sexist, misogynistic culture’ in No. 10

-

Local elections 2026: where are they and who is expected to win?

Local elections 2026: where are they and who is expected to win?The Explainer Labour is braced for heavy losses and U-turn on postponing some council elections hasn’t helped the party’s prospects

-

6 of the world’s most accessible destinations

6 of the world’s most accessible destinationsThe Week Recommends Experience all of Berlin, Singapore and Sydney