Can Enrico Letta save Italy?

The new prime minister–designate has a ton of challenges — not least of which is Silvio Berlusconi

Two months after frustratingly inconclusive elections, Italy finally has a new prime minister in the wings. The center-left Democratic Party (PD) garnered the most votes in the election, but not enough to form a government on its own or with the party of caretaker Prime Minister Mario Monti, which came in fourth place.

PD leader Pier Luigi Bersani resigned under pressure on April 19 after failing to fashion a governing alliance with Beppe Grillo and his anti-establishment Five-Star Movement — a strong third-place finisher, at 25.6 percent — and also failing to get his pick for president approved by even his own allies. The next day, parliament re-elected President Giorgio Napolitano, 87, to an unprecedented second seven-year term. On Wednesday, Napolitano tapped 46-year-old Enrico Letta as the next prime minister.

Letta, the deputy PD leader, was an unexpected pick from Napolitano. But, says Retuers' Gavin Jones, it's a selection "likely to please financial markets and Rome's international partners."

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

He is young, moderate and pro-European, and despite his low public profile he has been a member of the European political elite for many years. Letta speaks fluent English and has a sound grasp of economics. He is the second youngest Italian prime minister since World War II, yet with his wire-rimmed glasses and a hairline that has been receding for at least a decade, he exudes gravitas and responsibility. [Reuters]

Letta is also, perhaps, one of the few figures in Italian politics that has a plausible shot at forming a durable coalition government. He is from the moderate wing of the Democratic Party, but started his career with the now-defunct center-right Christian Democrats. And his uncle, Gianni Letta, is the top aide to former Prime Minister Silvio Berlusconi, whose center-right People of Freedom Party (PDL) party came in second in the election.

Forming a stable government won't be easy — as Letta readily admits. Berlusconi is making tough demands for his party's support, Letta's own PD is deeply fractured, and Grillo's movement is mainly concerned with overturning the system from the inside. But there are some points of agreement among most groups — notably, a desire to ease up on fiscal austerity — and if Letta "can navigate the obstacles and push through a reform of the electoral law and measures to help the economy, he has the credentials to be a dominant figure in Italian politics for the next decade," says Reuters' Jones.

Letta's odds of succeeding aren't great, but there is already a winner in this fight: Berlusconi, say Andrew Frye and Alessandra Migliaccio at Bloomberg News. "The three-time prime minister and two-time convicted lawbreaker won a path back to power in Italy by outmaneuvering rivals" after the election, and now Letta's government rises or falls at Berlusconi's pleasure. If it fails, Napolitano will call new elections, and Berlusconi's "popularity, opinion polls show, has only grown since" the last vote.

"The Letta government is an opportunity for Berlusconi to regroup, catch his breath and prepare for the next round of elections," Federico Niglia, a professor at Rome's Luiss Guido Carli University, tells Bloomberg.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

"It's undeniable that this is a victory for Berlusconi," Giovanni Orsina, also at Luiss Guido Carli University, tells The New York Times. "He got what he asked for, from Napolitano's re-election to a political government with broad, bipartisan support." But even if Berlusconi is "kingmaker by default," says Rachel Donadio in The New York Times, that doesn't mean he is strong. "Indeed, his party is splintering, held together only by the force of his personality."

Letta's real challenge, and opportunity, is to use his youth and novelty to change Italy's dysfunctional, deeply unpopular political system — or at least to make enough headway to convince Italian voters he is making a change. That won't be easy, either, says Donadio. Even though Letta will be one of Europe's youngest leaders, "he is less a new-guard politician than a compromise candidate palatable to his own imploding center-left party and to the center right — a young facade on a political edifice in the throes of collapse."

Like the current Greek government, a three-party coalition in which historical enemies on the left and right have joined together out of fear of extinction and a lack of viable alternatives, Mr. Letta is potentially the last gasp of a political cycle that in Italy began in the early 1990s with the collapse of the postwar political order and the rise of Mr. Berlusconi. [New York Times]

Letta's success or failure may well rest less on policy than on his ability to outshine the raging sun of modern Italian politics, says Stefano Folli at Italy's Il Sole 24 Ore. "I think Enrico Letta has to show he has a lot of political personality, because it's very, very hard to govern with Berlusconi without being put in a difficult situation."

Peter has worked as a news and culture writer and editor at The Week since the site's launch in 2008. He covers politics, world affairs, religion and cultural currents. His journalism career began as a copy editor at a financial newswire and has included editorial positions at The New York Times Magazine, Facts on File, and Oregon State University.

-

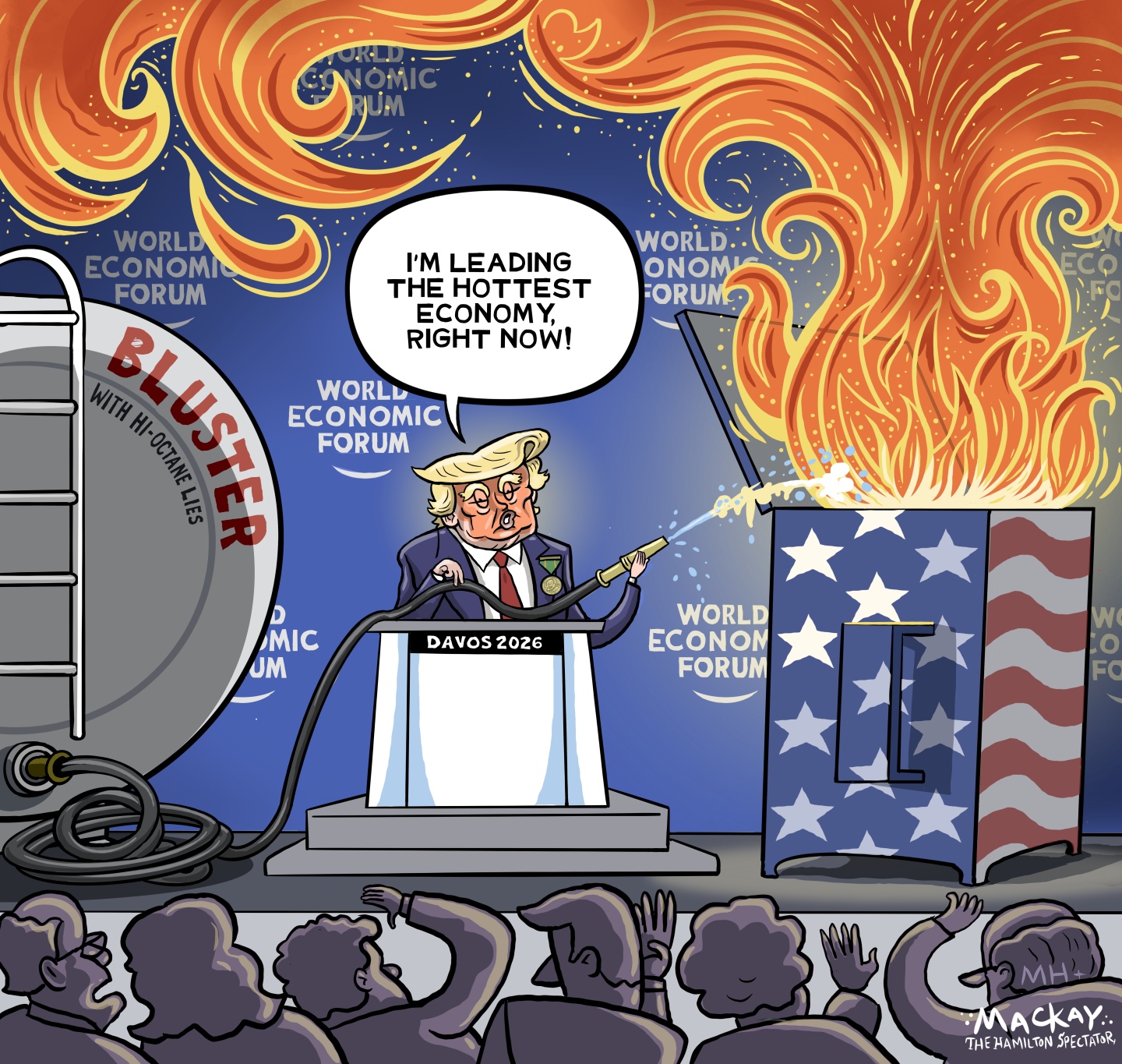

Political cartoons for January 25

Political cartoons for January 25Cartoons Sunday's political cartoons include a hot economy, A.I. wisdom, and more

-

Le Pen back in the dock: the trial that’s shaking France

Le Pen back in the dock: the trial that’s shaking FranceIn the Spotlight Appealing her four-year conviction for embezzlement, the Rassemblement National leader faces an uncertain political future, whatever the result

-

The doctors’ strikes

The doctors’ strikesThe Explainer Resident doctors working for NHS England are currently voting on whether to go out on strike again this year