The case for $22-an-hour minimum wage

Sen. Elizabeth Warren makes it, citing a study that shows we'd all be earning at least that much if wages kept up with gains in productivity

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

In his State of the Union address, President Obama called on Congress to raise the federal minimum wage to $9 an hour, from $7.25. A month later, House Minority Leader Nancy Pelosi upped the ante, pushing for $10.10 an hour in three years. Both of those proposals were pooh-poohed as politically impractical and economically suspect. But maybe Obama and Pelosi were actually lowballing the raise we owe low-wage workers.

How high should it go? Here's Sen. Elizabeth Warren (D-Mass.) at a Senate Health, Education, Labor, and Pensions Committee hearing last week, speaking to University of Massachusetts economist Arindrajit Dube:

If we started in 1960 and we said that as productivity goes up, that is as workers are producing more, then the minimum wage is going to go up the same. And if that were the case then the minimum wage today would be about $22 an hour. So my question is Mr. Dube, with a minimum wage of $7.25 an hour, what happened to the other $14.75? It sure didn't go to the worker. [Warren — watch below]

Dube agreed, then upped the ante again. If the minimum wage had kept pace with the rise in wealth by the top 1 percent of taxpayers, he added, it would have reached $33 an hour in 2007. Nobody, of course, is arguing for a $33-an-hour minimum wage, and Warren isn't even pushing for $22 — she just wants a bump to $10 a hour. But where did the $22 come from, and does it make any sense?

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

The actual number is $21.72, and it comes from an analysis by economist John Schmitt at the Center for Economic and Policy Research. That's only one of the numbers he churns out to argue that "the minimum wage is too damn low." In real dollars, the minimum wage peaked in 1968. If that had been linked to inflation (CPI-U), the minimum wage would be $10.52 an hour, and if you look at how the minimum wage fared against the average production worker wage, it would be $10.01 today. But the most egregious imbalance is productivity.

Between the end of World War II and 1968, the minimum wage tracked average productivity growth fairly closely. Since 1968, however, productivity growth has far outpaced the minimum wage. If the minimum wage had continued to move with average productivity after 1968, it would have reached $21.72 per hour in 2012 — a rate well above the average production worker wage. If minimum-wage workers received only half of the productivity gains over the period, the federal minimum would be $15.34. Even if the minimum wage only grew at one-fourth the rate of productivity, in 2012 it would be set at $12.25. [CEPR (PDF)]

However you look at it, Schmitt says, "by all of the most commonly used benchmarks — inflation, average wages, and productivity — the minimum wage is now far below its historical level."

Of course, not everybody thinks that raising the minimum wage is a good idea.

Linking productivity to wages is "one wildly flawed premise," says Erika Johnsen at Hot Air. "The value of productivity is not a constant," and much of the rise of productivity is due to technology.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Should the increase in crop yield from a farmer using a donkey and plow versus a farmer using a tractor be directly proportional to an increase in those crops' market worth because of some sort of imagined moral law about productivity and wages? No, because the market value of those crops has diminished as the ease of production has increased, and if that was the way the world worked, we'd all be paying a heck of a lot more for food right now..... Raising the minimum wage to some arbitrarily-determined level of ostensible just deserts is just another way of throwing market signals under the bus in exchange for more top-down control, which might benefit a few in the short run, but bogs down the entire economy in the long run. [Hot Air]

Johnsen then goes on to quote a New York Times op-ed by Christina Romer, the former head of Obama's Council of Economic Advisers: "Raising the minimum wage, as President Obama proposed in his State of the Union address, tends to be more popular with the general public than with economists." Romer's entire argument is a little more nuanced:

The economics of the minimum wage are complicated, and it's far from obvious what an increase would accomplish. If a higher minimum wage were the only anti-poverty initiative available, I would support it. It helps some low-income workers, and the costs in terms of employment and inefficiency are likely small. But we could do so much better if we were willing to spend some money. A more generous earned-income tax credit would provide more support for the working poor and would be pro-business at the same time. [New York Times]

Peter has worked as a news and culture writer and editor at The Week since the site's launch in 2008. He covers politics, world affairs, religion and cultural currents. His journalism career began as a copy editor at a financial newswire and has included editorial positions at The New York Times Magazine, Facts on File, and Oregon State University.

-

What to know before filing your own taxes for the first time

What to know before filing your own taxes for the first timethe explainer Tackle this financial milestone with confidence

-

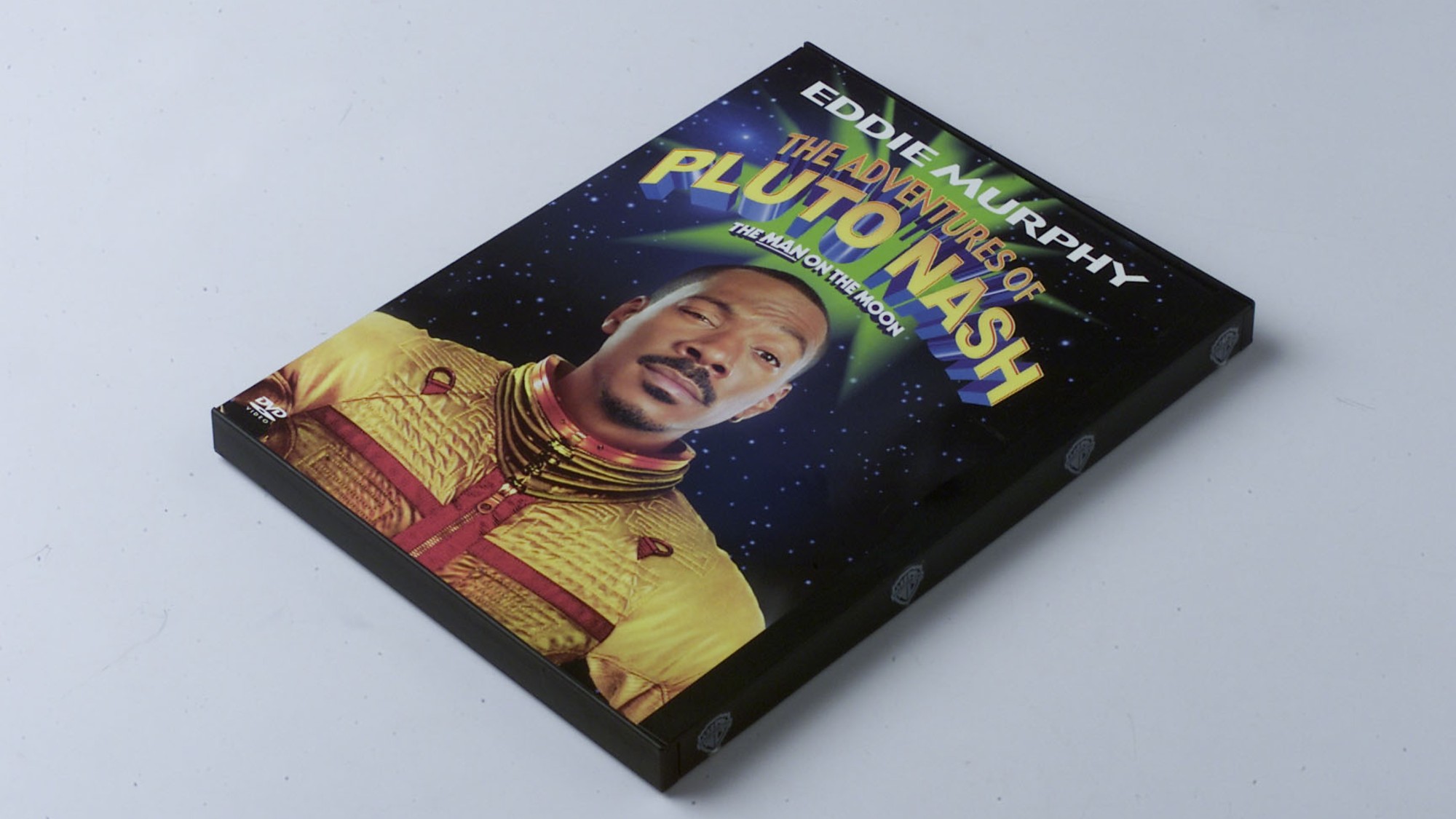

The biggest box office flops of the 21st century

The biggest box office flops of the 21st centuryin depth Unnecessary remakes and turgid, expensive CGI-fests highlight this list of these most notorious box-office losers

-

The 10 most infamous abductions in modern history

The 10 most infamous abductions in modern historyin depth The taking of Savannah Guthrie’s mother, Nancy, is the latest in a long string of high-profile kidnappings