Why CERN is 'confident' — but not certain — it's found the God particle

Scientists say the Higgs boson believed to have been found last July could very well be the real thing

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Yesterday a new pope was confirmed. Today, the God particle. Well, maybe.

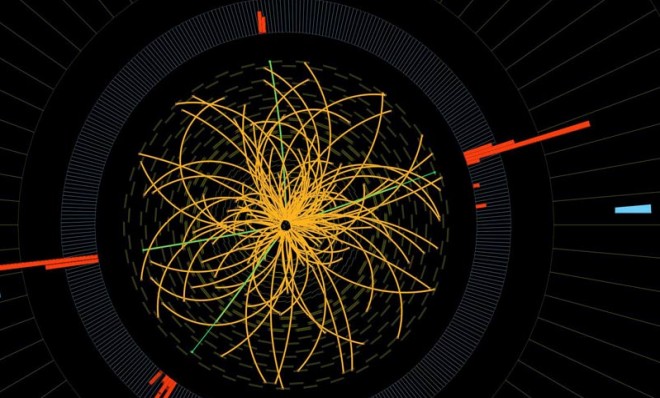

Scientists from CERN, the European Organization for Nuclear Research, announced early Thursday that after relentlessly poring over a year's worth of data, it's "looking more and more" like the July 2012 discovery was indeed the Higgs boson.

The elusive particle represents a missing cornerstone in the Standard Model of Physics. Theoretical physicist Peter Higgs first hypothesized its existence in 1964, and ever since, scientists have used it to plug holes in various mathematical equations used to describe the universe. The Higgs, for example, is thought to be the force that keeps the universe from unraveling, the invisible cosmic glue that keeps galaxies, stars, planets, and humans from combusting into the erratic protons that compose us.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

For the past few years, CERN scientists have been using the Large Hadron Collider to smash atoms together at fantastic speeds. After each crash, they have just milliseconds to sift through the ensuing wreckage for evidence of the Higgs — a process that's every bit as tedious as it sounds.

CERN's announcement:

At the Moriond Conference today, the ATLAS and CMS collaborations at the Large Hadron Collider (LHC) presented preliminary new results that further elucidate the particle discovered last year. Having analyzed two and a half times more data than was available for the discovery announcement in July, they find that the new particle is looking more and more like a Higgs boson. [CERN]

Scientists who are part of the collaborative effort between CERN's two lab entities — ATLAS and CMS, both of which ran atom-smashing experiments independently to corroborate results — are quick to qualify the God particle's existence as an "open question." A slight possibility remains that this Higgs is "a more exotic particle — possibly the lightest of several bosons predicted by other theories," says Hayley Dixon at The Telegraph. In other words: We still aren't 100 percent sure.

And yet the evidence is mounting. The Higgs particle is theorized to have two characteristics that set it apart from other particles: (1) It doesn't spin, and (2) its parity (a measure of how its mirror image behaves) should be positive. In their data set, CERN researchers were able to determine that the particle they've been studying indeed possessed both traits.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Which brings us back to an earlier point: What exactly would a universe without the Higgs look like? Here's what blogger Adam Frank told NPR last year:

It would all be photons. Everything would be moving at the speed of light, right. Which means at light speed, you wouldn't be able to have the kinds of structures we see today. You'd never get atoms and chemistry and rocks. So it's really important. The property of mass is really important for getting clumpy structures, essentially, like us. [NPR]

-

Why is the Trump administration talking about ‘Western civilization’?

Why is the Trump administration talking about ‘Western civilization’?Talking Points Rubio says Europe, US bonded by religion and ancestry

-

Quentin Deranque: a student’s death energizes the French far right

Quentin Deranque: a student’s death energizes the French far rightIN THE SPOTLIGHT Reactions to the violent killing of an ultra-conservative activist offer a glimpse at the culture wars roiling France ahead of next year’s elections.

-

Secured vs. unsecured loans: how do they differ and which is better?

Secured vs. unsecured loans: how do they differ and which is better?the explainer They are distinguished by the level of risk and the inclusion of collateral