Lost in paradise

The Unification Church is trying to build a new Garden of Eden, says Monte Reel, but so far, nobody’s coming.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

FOR ROUGHLY $6 a day, anyone can hitch a ride aboard the Aquidaban, a 128-foot floating market that runs a weekly route on the Paraguay River from the center of the country to its northern border. Dozens of locals have wedged themselves into the second deck. They include women and children, but most are men who scrape out a living clearing trees and brush for small-scale livestock farmers along the upper stretches of the river. Most speak the indigenous language of Guarani first, Spanish second.

I’m a conspicuous outsider. Occasionally, I catch the men staring at me and speaking in lowered voices, as if taking bets on what exactly I’m up to. They’ll never guess. I’m looking for paradise. I’ve heard it’s under construction just upriver in Puerto Leda.

THE REV. SUN Myung Moon, who died in September 2012 at age 92, founded the Unification Church in South Korea in 1954. In addition to overseeing the church, which he said aimed to fulfill Jesus’s unfinished mission by establishing a new “kingdom of heaven on earth,” Moon managed vast commercial interests and called himself a messiah. He was frequently accused of cult practices, in part because some of his hundreds of thousands of followers turned over very personal decisions—including the choice of marriage partner—to him. More than a decade ago, Moon told some members of his church that he wanted them to lay the foundation for a new Garden of Eden in one of the least hospitable landscapes on the planet—northern Paraguay.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

In 2000, Moon bought roughly 1.5 million acres of land fronting the Paraguay River. He turned Puerto Leda over to 14 Japanese men—“national messiahs” who were instructed to build an “ideal city” where people could live in harmony with nature, as God intended it. Moon declared that the territory represented “the least developed place on earth, and, hence, closest to original creation.”

Moon wasn’t the first utopian to favor Paraguay. Examine many European maps drawn between 1600 and 1775 and you’ll find something labeled Lago Xarayes at the head of the Paraguay River. Conquistadores journeying up the river confronted the inundated plains and confused them for a massive inland sea. Tribes spoke about a Land Without Evil on the far side of Xarayes, and the Spaniards believed that the same area hid a gateway to El Dorado, the lost city of gold. By the 1800s, most mapmakers correctly recognized the Xarayes as a mirage and relabeled it as part of the Pantanal. Still, the dream lived on for some. The 20th century brought utopian colonies of Australian socialists, Finnish vegetarians, English pacifists, and German Nazis. They all failed.

At the Puerto Leda dock, I meet a man who introduces himself as Wilson. He’s not a national messiah but a 44-year-old Chilean, a Moon follower who moved here two years ago. His wife and children are still in Chile. He offers me a ride to the complex. Within a minute, the headlights reveal a cluster of buildings. I can make out what appear to be several two-story houses, a water tower, a couple of large communal buildings, and a cellphone tower.

Wilson kills the engine in front of a structure that looks nothing like the humble riverside casitas found throughout this region, a district the size of South Carolina in which about 80 percent of the 11,000 residents lack running water. The building in front of us has a peaked terra-cotta roof, brick-and-stucco walls, expansive glass windows, and five air-conditioning units. At the front door, leather slippers wait for us. We remove our dirty shoes and step into the Rev. Moon’s Victorious Holy Place.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

All is silent. Wilson flips a switch, throwing light on what appears to be a dining hall. The large wooden tables could accommodate about 100 people. They are vacant. “There aren’t many people around right now,” Wilson explains. “But sometimes we have 100 working here at once.”

An ascetically thin Japanese man walks toward us, smiling behind wire-rimmed glasses. He pads across the glazed tiles with a hurried shuffle, as if he’s been waiting for us for years. He’s 62, and his name is Katsumi Date (pronounced DAH-tay), or just Mr. Date, as Wilson addresses him. He’s a national messiah.

“So,” he asks, “what is it you would like to see?”

Well, I’d like to see what 12 years of dedicated labor in pursuit of earthly perfection looks like. “Everything,” I answer.

The place, Mr. Date says, is all mine.

BACK OUTSIDE, I see huge dormitory buildings, guesthouses, and sheds for mechanical repairs. I count seven freshwater fish farms, fully stocked with pacu, a toothy species that looks like an overgrown piranha. I see no other people.

“Normally, there are about 10 of us who live here,” Mr. Date tells me. “But this week six are away in Asunción. So there are just four now.”

Mr. Date and I walk through early-morning light on smooth sidewalks, past manicured gardens of hibiscus and bougainvillea, beside an Olympic-size swimming pool. We enter a two-story communal building that resembles an office complex, climb a stone staircase to the second floor, and enter what appears to be a rec room. There’s a television, and Mr. Date pops a disc into a DVD player. The DVD, he says, explains everything.

The footage that flashes across the screen dates from 1999. We see the founding messiahs walk across untamed wastes—the grounds where we now sit. They lay bricks in wet mud. They sand metal frames. They wash dishes in the river. They wear heavy clothing, light fires to keep the mosquitoes away, and sweat in the wavy heat. They stagger through gale-force winds.

The rest of the DVD covers more recent developments. Messiahs erect the water tower. Man-made fishponds materialize on the grounds. A landing strip is planed flat by tractors. The messiahs unload saplings from the Aquidaban, then plant them in sprawling groves. A group of a dozen visiting Japanese students—the children of Unification Church members—help the messiahs build a school in a nearby village.

The fact that only 10 men live here comes rushing back to me. The colony has actually lost population since its inception, despite all the construction. Four of the original messiahs have returned to Japan. Only the hardest of the hard core have stuck it out.

And this raises a couple of questions: Who are these guys? And why have they put themselves through this?

IT'S NOON, THE midpoint in an unchanging daily regimen: up at 4:30 a.m. for a half-hour of silent worship, breakfast at 5, then back to their bedrooms to prepare for work at 6:30. Each is assigned a separate job: One fishes, another tills crops, another feeds the fish in the ponds. Someone checks the pH level in the pool, though no one swims. Lunch always runs from noon to 1:30. They’ll work until 5 p.m. and round out the evening with dinner and a short prayer meeting. That leaves them about two hours until the lights go out at 9. Most use that time to read, pray, or watch satellite TV.

I strike up a conversation with Norio Owada. Mr. Owada is 64, and manual labor and a good diet of homegrown vegetables have pared him down to a taut, leathery minimum. He’s a good example of your average founding messiah: a city dweller with very little experience in construction and even less in wilderness survival. His wife was selected for him by Moon, who was said to possess the ability to intuit good matches, and Mr. Owada left her in Japan with their children when he came here. He gets a church salary, which helps keep the colony solvent. His family and other members of the Japanese congregation provide more money, though no one can tell me how much has been poured into the place. Once every 11 months, Mr. Owada gets four weeks of vacation, which he can use to go to Japan. His wife has visited him twice since 1999.

In the beginning, the colonists hoped they would be joined by their wives (as well as more followers). Every August, they invite children of Japanese church members to visit for a couple of weeks, but so far none have chosen to stay on. “My wife thinks that it is not realistic for her to move here yet,” Mr. Owada says, “because we still have to raise the standard of living more.”

When I press him on how tough and lonely this must get, Mr. Owada says it doesn’t bother him. Moon sanctified his personal sacrifices, promising the men that spiritual rewards would make up for their suffering.

Months later, after Moon’s death from complications from pneumonia, I will once again reach out to Mr. Date to see if the True Father’s passing affects the messiahs’ dedication. It doesn’t. They plan to work on Puerto Leda for at least another decade.

OF COURSE, THERE is ecotourism potential here,” says Mr. Date. We’re standing outside an unfinished three-story brick building. Mr. Date refers to it as “the hotel,” but for the moment its only occupant is a stick-legged baby goat nosing around the food pellets being stored on the ground floor. Mr. Date begins running down the potential pluses of opening the place up to travelers: Tourism would allow people to see examples of sustainable living and take the lessons home with them. This Eden is intended to be an environmental paradise, he says.

We walk on, past planted fields of lemongrass, oranges, mangoes, grapefruit, asparagus, sugarcane. The crops are struggling. If agriculture alone is expected to support the colony, there are some kinks to work out. The men have planted thousands of jatropha trees, which can be used to make biodiesel fuel, but hundreds of parrots zeroed in on them and ate all the fruit. During the most recent wet season, rising waters flooded many of the thousands of neem trees.

“It’s been a hard year,” Mr. Date admits.

It’s clear that these guys have faith in miracles, and that’s exactly what’s needed here in Puerto Leda. Without one, the Victorious Holy Place seems destined to be another curious monument to human ambition and folly. But watching how hard the messiahs work, I can’t help but admire their tenacity. The fanaticism that underlies their devotion to this cause must burn hot, but they hide it well. They’re not evangelical. They’re friendly and welcoming to those who don’t share their beliefs. They’re reflexively humble and generous and admirably tough. They’re underdogs. The kind of guys you root for.

During the last hours of my visit, Mr. Date shows me something that might actually work out. “Japanese yams,” he announces, staring down at a plot of tilled soil. “They grow very large underground, up to 10 kilograms. They do well here.”

My immediate impulse is to celebrate this victory with hearty congratulations. Maybe all the sweat that Mr. Date has sunk into this plot will bear a little fruit. Maybe little victories like this can help other people in the Pantanal live richer lives. Maybe that’s enough.

Mr. Date stares down at the dirt. “Unfortunately,” he says, “they taste very bad.”

©2013 by Mariah Media Network. Excerpted from a longer article first published in Outside. Reprinted with permission.

-

What to know before filing your own taxes for the first time

What to know before filing your own taxes for the first timethe explainer Tackle this financial milestone with confidence

-

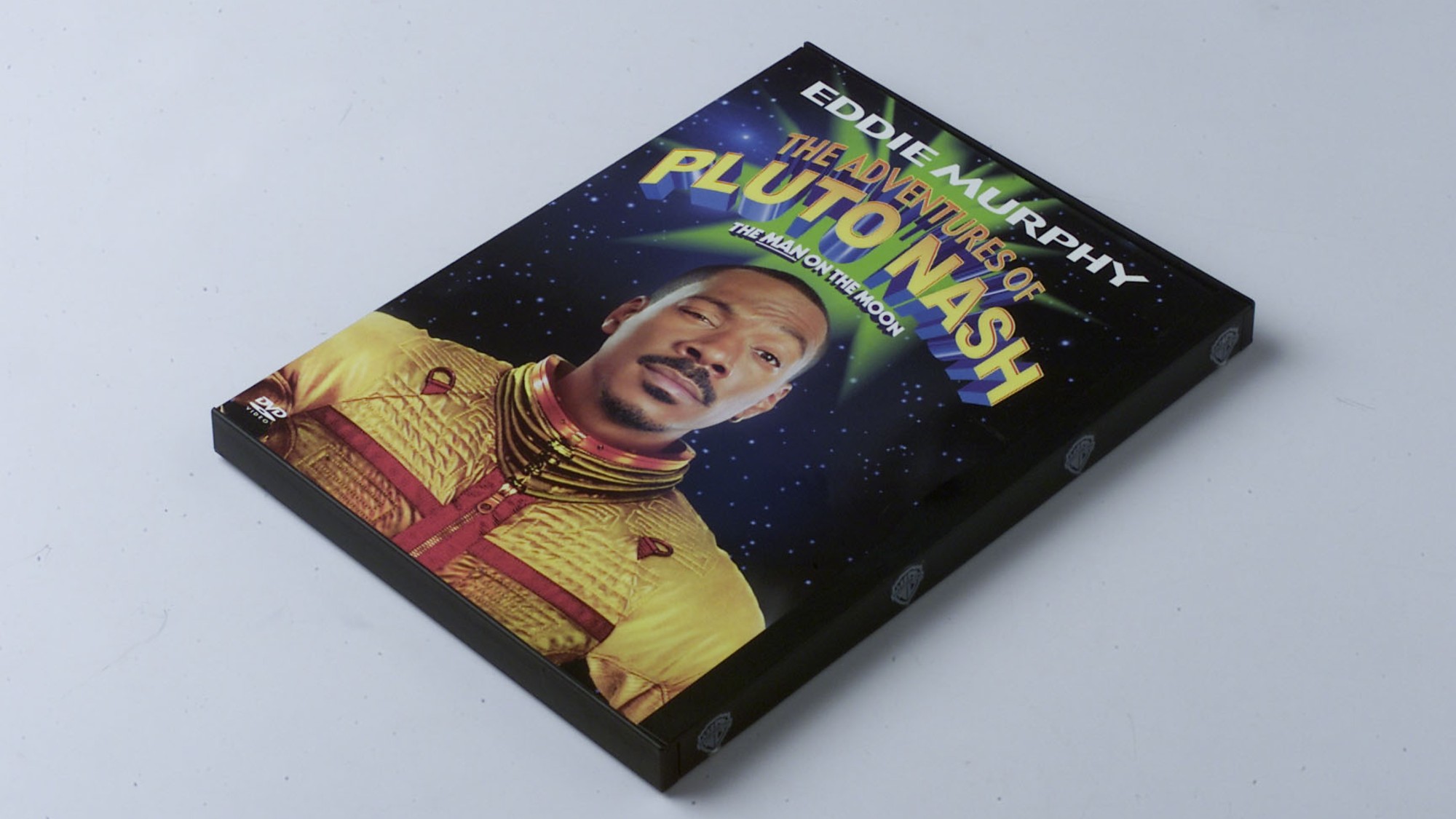

The biggest box office flops of the 21st century

The biggest box office flops of the 21st centuryin depth Unnecessary remakes and turgid, expensive CGI-fests highlight this list of these most notorious box-office losers

-

The 10 most infamous abductions in modern history

The 10 most infamous abductions in modern historyin depth The taking of Savannah Guthrie’s mother, Nancy, is the latest in a long string of high-profile kidnappings