5 smart reads for the weekend

The story of George McGovern's failed presidential campaign. A look back at Newsweek's first issue. And more compelling, of-the-moment stories to dive into

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

1. "Fear and loathing on the campaign trail in '72"

Hunter S. Thompson, Rolling Stone

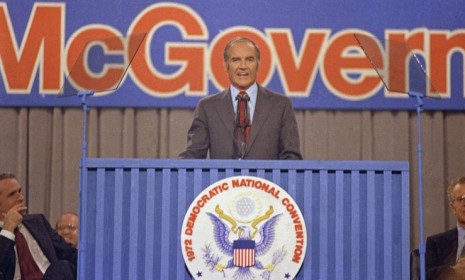

On Friday, The Washington Post reported that former U.S. Senator and presidential candidate George McGovern had been joined by family members in hospice as he nears the end of his life. With his health declining throughout the week, McGovern became unresponsive on Wednesday. McGovern's doomed presidential campaign, which culminated in a historic landslide loss to (the soon-to-be-impeached) Richard Nixon, was documented in a series of Rolling Stone columns by Hunter S. Thompson, later collected as a book called Fear and Loathing on the Campaign Trail '72. An excerpt:

Article continues belowThe Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

The Eagleton Affair was so damaging to McGovern's image — not as a humane, decent, kind, conservative man who wanted to end the war — but as a person who couldn't get those things done even though he wanted to. He was perceived, then, as a dingbat — not as a flaming radical — a lot of people seem to think that was one of the images that hurt him. But according to Pat, that "radical image" didn't really hurt him at all.... The same conclusion appeared in a Washington Post survey that David Broder and Haynes Johnson did.... They agreed that the Eagleton Affair was almost immeasurably damaging. . .. and according to Gary Hart, it was so damaging as to be fatal. Gary understood this as early as mid-September; so did Frank – they all knew it.

Read the rest of the story at Rolling Stone.

2. "Newsweek #1: A look back to the first week that was"

Bryce Zabel, Instant History

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

On Thursday, Newsweek editor-in-chief Tina Brown announced that the magazine, which began publication almost 80 years ago, would publish its last print issue on December 31, 2012. In a statement, Brown introduced a subscription-based digital publication called Newsweek Global, which will be available for web browsers and tablets: "We are transitioning Newsweek, not saying goodbye to it." A look back at the first issue of Newsweek — then called News-Week — from February 17, 1933:

Although both Time and Newsweek have become virtually indistinguishable to the average reader these days, both had a different cover philosophy when they started. Originally, Time was always that red-border with the famous person inside (at the beginning, always a photo). Newsweek, in contrast, was about the week in news. On this first cover, for example, you'll see seven pictures, each one representing a different day of the week. Monday started off with a speech by Adolf Hitler before 15,000 in Berlin's Sports Palace where he declared "the German nation must be built up from the ground anew." On Wednesday, for example, Franklin Roosevelt's election in the electoral college was certified by Congress. Clearly, these were monumental times for this new magazine: Hoover was out of office this week, Roosevelt was in — and across the Atlantic, the Nazis were consolidating their grip.

Read the rest of the story at Instant History.

Julie Schumacher, The Atlantic

During Tuesday's presidential debate, Barack Obama and Mitt Romney sparred over numerous issues, including health care and the inequalities that women face in the workplace. In a short fiction piece, Julie Schumacher tells the story of a female "professional patient," who uses her body as an educational tool for in-training medical students:

It isn’t exactly hard work, being a professional female patient. Every Wednesday at 3:15, I finish my classes (Introduction to Biology, Writing 2, and Family and Consumer Science) at the community college, then drive across town to the medical school/hospital complex, where I park in the visitors lot, flash my ID badge at the entrance, and head for the clinic. I strip off my clothes and stash them in a locker. I wash up. Then I put on a blue gown printed with shooting stars, and take my place on the paper-covered table in Exam Room 9. The students and interns trickle into the room in groups of two or three so they can learn from each other. They’re training in OB-GYN, in family practice, internal medicine, emergency medicine, even pediatrics. Some, as soon as the door closes behind them, are nervous laughers (where’s the hidden camera?), as if they suspect they might be the objects of a joke. Others, usually the women, are annoyingly reverent. I’ve seen plenty of hands tremble when they reach for the cotton bow to untie my gown.

Read the rest of the story at The Atlantic.

Larissa MacFarquhar, The New Yorker

On Tuesday, author Hilary Mantel won the Man Booker prize for her historical novel Bring Up The Bodies — the second in a planned trilogy about the life of Thomas Cromwell, an English statesmen who served in the court of King Henry VIII from 1532 to 1540. 2009's Wolf Hall, the first novel in the trilogy, also won the award, making Mantel the first British author and the first woman to win the Man Booker award twice. A profile of Mantel dives into her focused, obsessive writing process:

Occasionally, the problem is not too much control but too little: she will become so intensely involved in writing a scene that the only way out of it is to shut down consciousness altogether by going to sleep. The curtain must be drawn between acts. This is especially true if she’s writing about the past: she cannot simply put down her pen and reenter the present; there must be an intermission when the stage goes dark. This is how she remembers who she is and where she is. In the last months of writing a book, as the end comes in sight, she becomes possessed. She doesn’t go anywhere, or talk about anything other than the book. She stops only to eat. Her sleep and work hours become erratic: often she will wake up at three in the morning, write for several hours, and then go back to bed. She becomes more and more anxious: it feels to her like stage fright, unnaturally and intolerably prolonged, as though at last she were spinning all her plates at once, darting about from one to the other and terrified of making a mistake because she knows that if one plate spins off balance they will all come crashing down.

Read the rest of the story at The New Yorker.

5. "One small step"

On Sunday, Austrian daredevil Felix Baumgartner successfully completed the highest sky-dive of all time, using a helium balloon to rise more than 24 miles above the Earth before leaping with the aid of a pressurized suit. During his freefall, Baumgartner reached a reported speed of 833.9 miles per hour, making him the first human to break the speed of sound. The jump was streamed live on YouTube for an audience of more than 8 million people, setting a new record for the site. This essay explores how Felix Baumgartner has reminded us of the magic of flight:

A hundred years ago, before we took it for granted that we could all live on the moon if Congress would only raise taxes, a large public cared intensely about speed records, air races, parachutists, and feats of aerial daring. The morning newspaper brought the results of the latest sensational exploits. At the start of the 1911 Paris-to-Madrid air race, during which Louis Train crashed his monoplane into the prime minister of France, hundreds of thousands of people turned out just to watch the fliers take off. When Charles Lindbergh landed at Le Bourget Airport after flying from New York to Paris, navigating by the stars, the crowd pulled him out of the cockpit and carried him over their heads for half an hour. It was the era of zeppelins and astonishment. Flight, which had been a crazy dream for nearly all of human history, was suddenly something we could do.